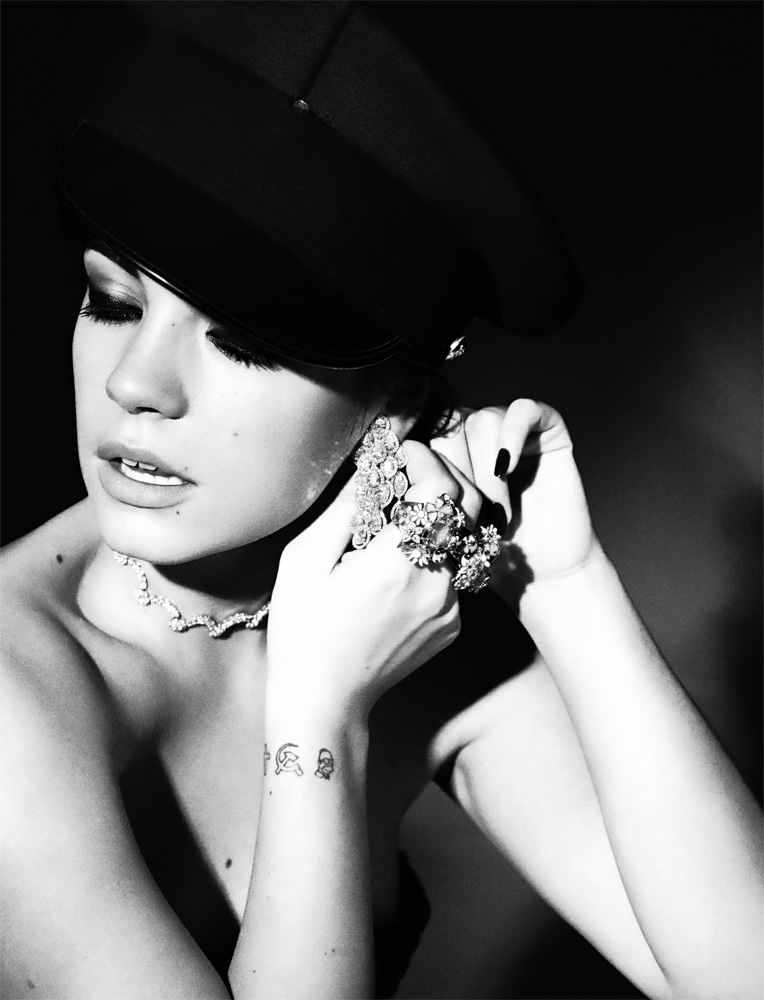

Lily Allen

In the last three years, Lily Allen has become a MySpace poster girl, released a hit record, achieved international fame, punched a paparazzo, gotten drunk at an awards show, slagged off Madonna, and kicked in the door for an undulating wave of nervy female British singers armed with varying degrees of wit and attitude. Along the way, she stumbled upon a new formula for how to become a pop star in the 21st century. The question now is if she can figure out how to stay one.

As anyone who has ever heard Lily Allen’s music can attest, she is a fervent believer in the shock-and-awe school of relationship songwriting. This is a method by which the singer demonstrates a complete disregard for certain conventional boundaries surrounding the discussion of one’s love life, declaring all subjects and subject matter—no matter how intimate or uncomfortable—fair lyrical game, and wrapping up these paeans to outspokenness in a musical package that’s as inventive as it is uninhibited. It’s the kind of songwriting that, for example, produces couplets about the lackluster endowment of one’s former boyfriend sung over irresistibly infectious, dub-tinged pop tracks. It’s also a big part of the soulful British girl-power-charged revolution that Allen—the daughter of British actor and television presenter Keith Allen—ignited a few years back with the release of her debut album, Alright, Still (2006), kicking open the door for Amy Winehouse, Duffy, Adele, and numerous other singing ladies with big voices, attitudes, and romantic bones to pick. This month, the 23-year-old Allen returns with her sophomore effort, It’s Not Me, It’s You (Capitol), on which the themes get more all-encompassing (God, mortality), the subjects more involved (self-medication, daddy issues), and the artist emerges an older, wiser, more fully realized animal—albeit one with the capacity to deal with the aforementioned material in earnest and still write a song entitled “Fuck You.” Damien Hirst, who has known Allen since she was a schoolgirl spouting off about the boys in homeroom, recently met up with the singer at Claridge’s hotel in London.

DAMIEN HIRST: How old were you when we met?

LILY ALLEN: About 3 years old.

DH: I met you at 3? No . . .

LA: I was pretty young.

DH: Yeah, you must have been. You were probably 6 or something like that. You used to come to Gloucester [music festival] with us. You came, like, three or four times or something.

LA: No, you came with us three or four times. I went about 10 million times. You stopped coming.

DH: Yeah. I started to hate it.

LA: It was like all of the people who were there had completely lost it on acid. This girl came up and was like, “Have you seen my boyfriend, Jacob?” I said, “What does he look like?” And she went, “He’s about this big.” [gestures with fingers]

DH: About three inches.

LA: [both laugh] I was 14 years old.

DH: Maia [Hirst’s wife] went to Glastonbury [music festival] one year. When she got back, I said, “How was it?” She said, “Great, but I got stuck in the elevator for about two hours.” I was like, “The elevator in Glastonbury? Where were you going?” She said, “To the subterranean bar.” And I was like, “Oh, my God! There’s no elevator and no subterranean bar at Glastonbury!” But if you saw it at Glastonbury, then it must have happened . . . Anyhow, I’ve known you all this time.

LA: And look how far I’ve come.

DH: You could say that at this point you’ve outshined your father. And he’s quite good about it, isn’t he?

LA: Yeah, he’s really happy. But there’s a thin line between jealousy and pride.

DH: Of course. Sometimes it’s difficult.

LA: But Dad and I are the only father-and-daughter acts who have both had No. 1 songs in England.

DH: I love facts like that. For example, do you know the only pop group with a name that’s a palindrome to have a chart hit with a title that’s also a palindrome?

LA: Was it a-ha?

DH: Close. It was ABBA, with “SOS.”

LA: A-ha was quite a good guess, though.

DH: So would you say you were an overnight success?

LA: Well, since you’ve known me for so long, would you say that I was?

DH: No, but I do remember all of a sudden picking up a newspaper one day and seeing that you were on Top of the Pops. It seems like it happened overnight . . . But maybe I was just taking lots of drugs.

LA: You weren’t taking drugs at the time—you’d stopped by then.

DH: You had a deal with London Records, right?

LA: That was years and years and years ago.

DH: But even the stuff I heard you making back then—I thought it sounded brilliant. And original as well, which was a bit surprising.

LA: Its originality surprised me, too, actually. I don’t know . . . Is the kind of success we’re talking about ever not overnight? But I do think because of who my dad is, people were ready to make a celebrity out of me.

DH: I love this quote that you said: “Everyone is so obsessed with celebrity culture. They

presume that because my dad has been in a couple of B movies and wrote some shit football song,

I’ve been driving around in limos all my life.”

LA: That was quite funny.

DH: But, you know, we got asked to rerelease “Vindaloo” [the hit song that Hirst collaborated on with Keith Allen and Blur’s Alex James for the 1998 World Cup] a year or two back, and your dad said no because it would interfere with what Lily’s doing.

LA: Yeah, he’s good like that.

DH: So you got into performing and singing because of your dad’s connections, and then you screwed your way to the top . . .

LA: I screwed my way to the middle.

DH: See, I got success very early, and then I fucked my way to the bottom. When did you know you were going to get singing for a career? Were you entertaining at school?

LA: No, not at all. I wasn’t into anything at school. I used to get really embarrassed. I used to get asked to do performing things, and I’d go to all the rehearsals, and then I’d pretend to be ill on the day I had to actually perform. I was very unhappy at school. I didn’t get on with people my age.

DH: Why was that?

LA: I don’t know. Adults were far more interesting. I think I spent too much time with adults, and I just thought kids were stupid.

DH: Do you think you missed out on anything?

LA: Not at all. I feel like I got quite a lot of stuff out of the way that people my age are just kind of confronting now, like alcohol and drugs and relationships. Are you allowed to smoke in here?

DH: You’re not—unless you sit by the window. Why don’t you go sit by the window?

LA: Why don’t you grow up?

DH: I quit smoking . . . But I like the way that people who start out young have to kind of grow up in public, and the way that everything sort of changes. Do you ever think about how you’re changing or how you’re going to change?

LA: Yeah. I’m a different person now than I was a few years ago when my first record came out.

DH: Do you have writers and producers who you work with?

LA: Well, I have producers who I write my songs with. This record I did with one person, Greg Kurstin. He did all the music and I did all the lyrics and melodies that I’m singing. I write and record at the same time, so I make it up as I go. I can’t write things when I’m not working. Like, if I’m home, I’d rather just watch TV. I don’t want to go home and write songs.

DH: Do you think about direction at all?

LA: No. Nothing is premeditated or preconceived.

DH: So how is this new album, It’s Not Me, It’s You, different from your first album?

LA: It’s a bit darker. There’s a lyric in the song “Him” that you’d like. It’s about humanizing God. The verse goes, “Do you think he’d drive in his car without insurance/Now is he interesting or do you think he’d bore us/Do you think his favorite type of human is Caucasian/Do you reckon he’s ever been done for tax evasion/Do you think he’s any good at remembering people’s names/Do you think he’s ever taken smack or cocaine/I don’t imagine he’s ever been suicidal/His favorite band is Creedence Clearwater Revival.”

DH: Do you believe in God?

LA: No.

DH: I’m glad we got that one out of the way.

LA: I also don’t believe in sports.

DH: You’re smoking in my room. I hate that.

LA: Oh, God! I’m talking to a man who literally breathed smoke into my crib when I was a baby.

DH: Except we’ve already established that I met you when you were 6.

LA: I was still in a crib when I was 6.

DH: I am so glad I don’t smoke anymore. It’s a nightmare, smoking. You have to be so committed.

LA: I know.

DH: I used to smoke even when I was ill—first thing when I’d wake up in the morning.

LA: That’s my favorite smoke—when I’ve got a chest infection.

DH: In an interview recently, a guy said to me, “I was looking through your old interviews, and I read something where you said that you don’t trust people who don’t smoke. What do you think about that now?” I was like, “Oh, well, now I don’t trust people who do.” What a chameleon. What do you think about the fucked-up state of the music business? Do you think you’ll have to invent a future for yourself?

LA: No. I just hope I can stay famous enough for a little bit so someone rich will marry me. [laughs] That’s all I really care about these days. You should worry if you’re a boy in a band, but not if you’re a girl.

DH: But I suppose if fewer people are buying records, then it becomes more about performing.

LA: Because you actually get money for performing, and you don’t really anymore from selling records.

DH: But then you have the punishing schedule.

LA: Yeah, I do. I can tell you exactly what I’m doing to the hour each day in a year. It drives me fucking mad.

DH: When do you get time to make new stuff?

LA: I don’t really. I need to put aside time to do that.

DH: Have you got a shrink?

LA: Yeah. I was supposed to see him this morning, but I forgot. I’m glad I didn’t go, because I would be really tired right now if I had. My appointment was for 9 a.m., so if I’d gone, I would have had to get up at 7 a.m., gone to my shrink, and then gone straight from my shrink to a photo shoot, and then I would have done that all the way until now. And then I have a dinner after this that will go until at least 11 p.m., so I would have done a pretty long day. I’m a busy girl.

DH: Doesn’t that make you want to fuck it all off?

LA: I schedule holidays.

DH: You’ve got to try not to pencil too much into the future because in a year’s time, you will definitely have changed. There’s always booze as well.

LA: I don’t drink anymore.

DH: You’ve stopped for good?

LA: I’ve stopped for the foreseeable future.

DH: Was the drink getting out of control?

LA: No. I just decided that I didn’t want to give people ammunition to write things about me. I mean, I’ll just take cocaine now without any alcohol. [laughs]

DH: I’ve tried. It’s a nightmare. You become a jibbering wreck.

LA: God, I can’t imagine what that must be like.

DH: Yeah, it’s stupid. It’s the most horrible thing in the world. You’re just totally wired. And because everyone else around you is drinking and you’re not, it makes you really want to drink. But you don’t drink, so you just have more cocaine, which makes you more wired, and then everyone else sort of crashes out, and you say, “I hate myself.”

LA: I’ve been getting into art recently. I don’t know if you knew that.

DH: I heard you bought some paintings by Paul Simonon from the Clash.

LA: Yeah, and I bought a Christian Marclay piece off Jay Jopling [art dealer and gallerist].

DH: Really? What did you buy?

LA: This piece called Untitled (Guns N’ Roses and Survival of the Fittest), which is this thing of tapes.

DH: You’re mental! What got you into that? You’ve got more money than sense, buying that rubbish. I bet you like those fucking guys who cut them cows in half and do all that rubbish. That’s not really art! [both laugh]

LA: That’s a good thing to buy, art. Isn’t it? In this day and age? In a recession?

DH: Yes, it is in any time.

LA: You timed your auction quite well, didn’t you?

DH: Yeah, I think I was very lucky.

LA: If it had been a week later, it could have been a different story.

DH: If it had been 24 hours later . . .

LA: Do you think?

I just hope I can stay famous enough for a little bit so someone rich will marry me. That’s all I really care about these days.Lily Allen

DH: Yeah, it would have bombed.

LA: Was the credit crunch the day after?

DH: It was on the actual day of the auction—that was the day of the crunch. I woke up in the morning and in the newspaper it said, “Black Monday.” I thought, “Oh, shit. The crunch.”

LA: I don’t know how they’ve managed to brand the recession. I think I might start to make my own cereal called Credit Crunch. It would just be a cereal laced with speed so you don’t need to buy food for the rest of the day.

DH: So here’s a beauty question: What are some of the obstacles you’ve confronted as a woman?

LA: Putting on a bra is quite complicated.

DH: Have you got any long-term friends who you’ve taken with you into this newfound stardom?

LA: Yes.

DH: I think that’s important. I always get suspicious of famous people who’ve only got other famous people as friends.

LA: Well, I’ve never had any friends who are really famous who I didn’t already know.

DH: Is it work for you then, doing what you do?

LA: Yeah, it’s hard work.

DH: If a guy jumped on your back, would you leave him on or jerk him off?

LA: I’d leave him on.

DH: What about all this attention you’ve gotten? How do you feel about it?

LA: I love it. That’s why I do what I do.

DH: The attention is good, isn’t it?

LA: Oh, yeah. It’s brilliant.

DH: How would you like to be remembered?

LA: I don’t care what people think of me now, so why would I care when I’m dead?