The Tender Hand of JD Souther

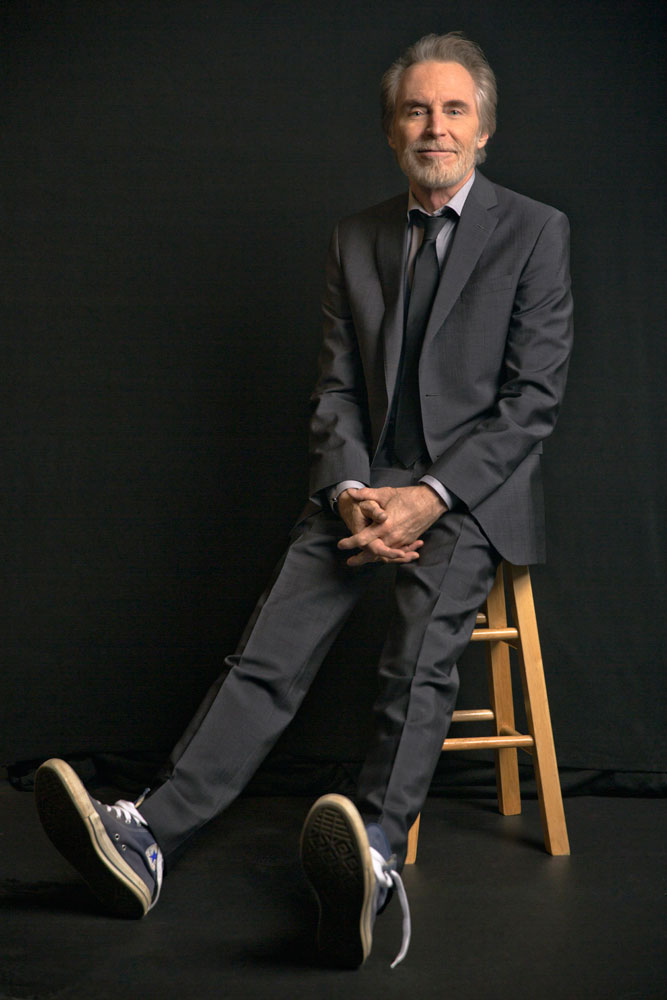

ABOVE: JD SOUTHER. PHOTO COURTESY OF JEREMY COWART

JD Souther is one of the most celebrated songwriters of his generation. Chances are, if his name doesn’t immediately ring a bell, then one of his songs most certainly will. Souther had a hand in penning some of the most memorable songs from the ’70s and ’80s, including hits for The Eagles, Bonnie Raitt, James Taylor and, of course, himself. (His track “You’re Only Lonely” was a classic hit of 1979.) Souther, along with a cadre of like-minded musicians, came to be forever associated with the country-rock aesthetic of late ’70s California, a vibe that continues to inspire musicians today. His reputation as a songwriter—a position solidified by his induction into the Songwriters Hall of Fame in 2013—is as legendary as his storied personal life, which includes now-mythical love affairs with the likes of Linda Ronstadt, Judee Sill (her song “Jesus Was A Crossmaker” was famously written about him), and Stevie Nicks.

That being said, however, Souther’s work is much more dynamic and multifaceted than just the mellow, golden ’70s music with which he is commonly associated. Raised on a steady diet of big band and jazz during his childhood, Souther has routinely returned to that music—as well as the genius songwriters of the early 20th century (Gershwin, Cole Porter)—for inspiration. On his new studio album, Tenderness (out tomorrow, May 12), Souther combines these musical threads, striking a perfect balance between understated jazz and the ineffable pop narratives that have been the backbone of much of his greatest work. Prior to the release and just before his show this past weekend, we sat down to speak with the musician in New York.

T. COLE RACHEL: Congrats on your new album. I know you are sneaking into New York this weekend to play a show at the Café Carlyle.

JD SOUTHER: I always wanted to play the Carlyle and I hope after the album’s out we’ll be back at the Allen Room or some place considerably bigger, but I love the Carlyle. I used to stay there in the ’70s. I used to go see Bobby Short there when I was really young.

RACHEL: Do you enjoy being on the road and playing live in front of people?

SOUTHER: At one point I took 25 years off from it, [so] I can’t say that it was always great, but yeah, I love performing. I love playing music with my friends in front of an audience. I can’t say the traveling part is that much fun anymore.

RACHEL: I love that your new record really plays like an album. I think people have sort of forgotten the art of making an album, or what it means for something to be of a piece, not just a collection of singles that you’re going to maybe buy one or two of from iTunes.

SOUTHER: I very much appreciate you saying that. It was designed as a set. I wanted it to work as a collection of songs and the album is kind of cinematic anyway, with those beautiful string charts by Billy Childs and some fairly exotic instrumentation from me. I just wanted it to be like a little noir film. I hope every song stands on its own, but it was really designed to be a good short film and a good set that you could listen to top to bottom and feel satisfied.

RACHEL: You’ve kind of flirted with making this kind of music before, but I feel like this record really shows off a lot of your influences that people may not know about. So many people might still associate you with a ’70s California thing and this really speaks to your love of jazz music and great American songwriters.

SOUTHER: Thank you. I think I’ve been influenced by everything I’ve ever heard. The first thing I ever heard was my grandma, who was an opera singer. The first song I ever learned was the Nessun Dorma from Puccini’s Turandot. My father was a big band singer, so I used to hear him walking around the house singing standards all the time. By the time I went to school, I probably already had had—whatever the conscious years are between [ages] one and five—complete saturation with Cole Porter, George Gershwin, Rodgers and Hammerstein, Jimmy Van Heusen, Sammy Cahn, Jules Stein, Dorothy Fields, all those standard writers. That was just the repertoire at our house. My parents didn’t like country music, so that I discovered via rock ‘n’ roll later on. I played in rock ‘n’ roll bands all through school, but I never lost my love of this kind of music, mostly this kind of song construction. Think back to the early rock ‘n’ roll records and the average record length in the ’50s—and well into the ’60s—was two and a half minutes. It’s very hard to put that much songwriting into two and a half minutes.

RACHEL: You’ve always had such a great flair for creating narratives in your work. I know people often say that all songwriting is really just telling a story, but there are certain songwriters that are more like literal storytellers. My favorite songs of yours, “New Kid in Town” for example, really work like little short stories.

SOUTHER: I think people are in such a hurry now to get to something catchy. When I started making records, the real square guys would always say, “Don’t bore us, get to the chorus.” Nowadays it seems like people want something of a hook even in the intro and something really recognizable even in the first verse, at the sacrifice of possibly depth or storyline. Maybe we should amend that quote to say every song should tell a story.

RACHEL: Yeah. It’s a little depressing how much contemporary music isn’t really about anything. It’s about repeating a mantra; it’s all hook.

SOUTHER: I try to tell as much of story as I can. There’s always subtext; in a couple of those songs you have a really sinewy under story going on, but they all, I hope, go somewhere, like a little journey. I think of this album as a trip down the L.A. streets after it’s been raining for two days and it’s at night. It feels that way to me, like a Raymond Chandler book or something.

RACHEL: It’s cool to hear you talk about jazz, too, because it’s so rare. I interview so many artists and they never want to acknowledge the importance of jazz on contemporary music.

SOUTHER: I know! I talk about it sometimes and very often that part of what I said doesn’t get into the finished interview. It’s the music I grew up on. I started playing on violin for a year in fourth grade, but I got tired of defending my violin with my life after school. I had also fallen in love with jazz by then, so I wanted to play tenor sax, but I was a small kid and it was a little unwieldy for me. So I learned to play clarinet, which is the same key, same fingering. Then, when I was 12, I discovered drums and it was all over. I was a jazz drummer the rest of my life. I had a jazz trio, a rock ‘n’ roll band, and I played drums in junior high, high school, college, big bands, and I played timpani in the symphony. I am a drummer. It’s the one instrument I actually play pretty well. It’s just hard to carry on your back.

RACHEL: It’s not easy to lug around a drum set.

SOUTHER: I wanted something tonal that I could write songs with and someone left a guitar in my apartment in 1968 back in L.A. I’d never even held a guitar until then. I started noodling around on it and I thought, “Well shit. Not only can I play chords and voicing and find melodies and counter melodies on here, I can also put this thing on my back and get on my Triumph motorcycle and get to the Troubadour and back.” It was almost that simple.

RACHEL: I’ve spent a lot of time with bands and people who make songs, but I still find the process of songwriting so fascinating and mysterious. Do you find that your way of working or the way you write songs or even the way that you think about constructing songs has changed a lot over the years? Or do you still sort of have the same mindset?

SOUTHER: The mindset is probably always the same. It’s a little three-step thing that happens in the very beginning: “Oh, I’ve got a great idea. Quick find a paper and a piece of pencil or a piano,” and then you pause and think, “Oh God, is this really a good idea?” Then everything else after that is just filling in the blanks, or trying to concentrate, or meditate, or medicate, or something, your way back to the original thought because that’s the kernel that began the tree. It’s like biology. It has all the information and its DNA that you need to write the song. All you need to finish it is patience, and a good musical vocabulary helps and being well-read helps too. You really need to find whatever that spark was that made you leap out of bed at two in the morning, scramble for your No. 2 pencil and pad, and illegibly put down six or eight lines. Sometimes the next day you find them and they’re pretty darn good. Other days you just think, “Oh, maybe not.”

RACHEL: Do songs usually begin for you, in your mind, with lyrics before melodies or before music?

SOUTHER: I’d have to say, on average, there’s probably no methodology. I have a wonderful piano that I really love, a handmade Yamaha grand. Sometimes I’m sitting there and it sounds so good that I find some little melody or a phrase that leads me into a song, but probably more often than not I actually grab a notebook. There are journals scattered all over houses on my farm and I write something down and hope I find it later. As I said, I hope I can return to the idea with some sense of what put me on the chase to begin with.

RACHEL: It’s a funny process, kind of mysterious…

SOUTHER: I was watching an interview with Paul Newman once years ago on that program James Lipton has, Inside the Actors Studio. Newman was trying to explain something about a scene or a performance, and he got tangled up in the explanation, threw his hands up, and went, “I don’t know, it’s all smoke and mirrors!” My friends who I was watching it with were both actors, and one of us said, “What a cop out,” and the other one said, “You know, he’s kind of right.” There’s a certain part of assembling a piece of art, or in the case of painting, just knowing when to walk away from it, that really, you can’t quite plan, study, or prepare for. You have to have some degree of luck on your side.

RACHEL: I think that’s true for all art, really. Is songwriting a skill that can be learned? Or do you find that most great songwriters have some innate knack for it?

SOUTHER: My friend, a brilliant novelist and poet Jim Harrison, always says that you have to be a great reader to be a great writer. I think the same is true for music. You have to be a really good listener. I think one of the things that’s made Linda Ronstadt’s career so incredibly rich and powerful and valuable to all musicians is that she has what jazz guys call “big ears.” She hears everything, and she really is more responsible for my career than almost anyone else because she was in my house when I was writing the first songs that I thought were good. She just set such a high bar. She picked the best songs of mine, the best of Warren Zevon’s, the best of Lowell George, the best of Jackson Browne, and she did the best of Karla Bonoff’s. She was an incredibly astute listener—not to mention an absolutely stunning singer and interpreter. Listening is everything. If you don’t listen to a lot of music, you won’t know a lot of music. It’s that simple.

RACHEL: Having written so many songs that have been interpreted by other people in different places and times, I would think that, as a songwriter, it must be so satisfying to know your work continues to have a life out in the world and see it re-imagined by other people. Are you ever surprised by that?

SOUTHER: When I hear new recordings of songs of mine, particularly songs that have been around for a while, I’m always delighted. I don’t even think about whether it’s a good performance, I’m just intrigued, and the stranger the interpretation, the better. I don’t know if you’ve ever come across this, but there is a Taiwanese hip-hop girl band called S.H.E. that has a version of “You’re Only Lonely” that is incredible. It has hip-hop verses after every chorus. They look like they’re 15, these little Taiwanese girls. I don’t think they’re actually playing any instruments; one of them has got a turntable and one of them is kind of holding an electric guitar, one’s kind of holding and playing a keyboard. But they’re just singing and they adhere faithfully to the song, and then they have a hip-hop verse after every chorus.

RACHEL: That’s so wild.

SOUTHER: It’s on YouTube. It’s just cool as can be.

TENDERNESS IS OUT TOMORROW, MAY 12, VIA SONY MASTERWORKS.