Never Stop

There are a few near-inevitabilities attached to being an iconic band with a 30-year history. There are the breakups and solo attempts; the public disputes and eventual reunions; the deaths and births and divorces and tragedies that befall the members along the way. There is also the threat of irrelevance.

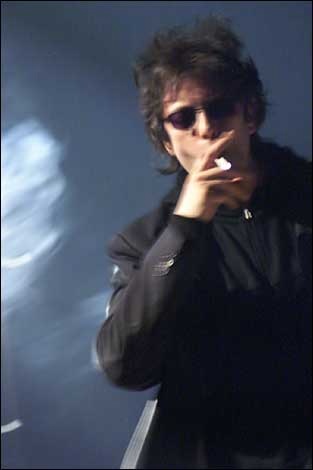

Echo & the Bunnymen is a band that rode to fame as a part of the late-seventies British post-punk musical phenomenon, and managed to earn that rare mixture of commercial success and cult-icon status with their inimitably haunting, psychedelic, and melancholic anthems. (One of their most iconic songs, “The Killing Moon,” was used for the number one in weirdo teen-angst film epics, Donnie Darko, if that tells you anything.) Over the years, they have survived a breakup, the death of two members (both by motorcycle accident) and any number of hurdles fit for a band with a lifespan that outlasts most marriages. But they’ve also managed to put out more than ten records’ worth of ever-evolving work. This week, The Bunnymen released their latest, The Fountain (produced by John McLaughlin and featuring Coldplay’s Chris Martin)–and it’s such a departure for the group that lead singer Ian “Mac” McCulloch has called it the equivalent of a debut record. This Saturday, Echo & the Bunnymen will take the stage at New York’s Mercury Lounge. We spoke with Mac about his experience making his 11th album in 33 years.

MADISON: Thanks so much for doing this. How’s it being back in New York?

McCULLOCH: I still feel dwarfed by New York. That’s a good thing. I do feel comfortable here as well, and excited. But Peter, my manager, he said, you know, “We can have this! We can, we can have the city!” [Laughs] I said, “Petey, no. No one has New York. You just kind of enjoy it while you can in whatever way. But New York has you.” I’m not sure I could live here. Maybe when I was younger, but I need space now.

LM: Let’s talk about The Fountain. I thought the album was great, and quite different from what you’ve done in the past. I read that you felt that, in some ways, it was like a debut.

IM: It felt like that. It was like, where’s all this energy coming from? Well, I knew what it was; it was the production side: John [McLaughlin], Simon [Perry], Dave [Thomas], gave it a lot of attack. And a lot of the drumming is actually programmed.

LM: Oh yeah? Back to the drum machine…

IM: Well, kind of, but Dave’s the best programmer of drums I’ve ever heard in me life. ‘Cause he worked out his beats, you know–he didn’t just go, “Oh doon-doon-doon-doon.” I think on this album, down to the drums and bass, we’ve all toughened up. And I’ve wanted that for years. Pete de Freitas was the best drummer in the world. I think finally there are elements of what I think Pete would be drumming like if he was alive now. It’s more exciting, this record. And everything sounds like it’s in your face, which is what I wanted. We wanted to master it loud and mix it loud. That was always one thing–we’d get our records and be like, “Why are these so quiet?” And they would be quieter even on the radio when everything was compressed. So that was something I wanted to address finally. There’s a punkier angle to the bass and drums on this record. But like, proper Chris Thomas-produced Sex Pistols punk rather than, you know, the other kind of scruffy punk.

LM: How has the recording process changed for you over the years?

IM: Well, this album was co-written with people. It was a production team. I went down to London to kind of listen to what they are with the view of maybe working with them on other stuff. They said, Here’s the mic, and within seconds, “I Think I Need It Too” had the whole melody, most of the lyrics–within minutes. I had one chorus and then I went for a piss. In one side of my head I was doing the guitar and then I went back in–probably should have washed my hands-and said, “I’ve got all the chorus, but I’m singing it in me head so give us the mic and just go straight to the chorus so I don’t get confused.” And then we went into it. I knew after listening to that one, just that one thing. Even going to the toilet, it was that excitement–like, “I’ve got to get back in there!” It was just a different way of life for me and it’s what I wanted. I play most of the guitars. I’m bass, I’ve never done that on the album. Keyboards as well, which I’ve never done.

LM: The record has a whole different feel to it, which I think is interesting. It’s much more accessible than some of your earlier stuff.

IM: I would say it is different. But to me it’s only because it’s more in your face. Some of our records you have to listen to more because, you know, most people are pretty one-dimensional. So we try to give them as many dimensions on this record while still catering to their simplicity. And it’s good to have a record that, you know–in the past, some of our records, you can’t just have them on. You have to sit down. But with this, you can just turn it on. And those records are good as well. That’s something that is good to be reminded of.

LM: I was reading some interviews before this, and it seems like people are really compelled to compare you to U2. Not in terms of the music, but the trajectory of your careers. I thought that was a little bit strange, because obviously you’re so different.

IM: Yeah, but that’s what you do. But this “trajectory”–they were born knowing where they were going, you know? They were probably born to the same mum in four different wombs. I don’t know if you can be fan of U2 and expect … they have some good tunes, but you’re not going to get anything emotionally rewarding out of it. People do, you know, there’s a lot of people who believe that Bono’s saying something. He’s so disgustingly creepy. Plus, he’s out of his fucking mind as well. You know, all of this born-again Christianity. That was his whole thing in the ’80s. When he came to America and wore the cowboy hats and said, “We’re born-again Christians.”

LM: Ha, right, I forgot about that. It’s weird, though, they’ve been together forever. For awhile, it looked like the Bunnymen were really done for good. What made you want to return to the band?

IM: Yeah, it was in the ’90s that we were apart. And then a friend phoned up–he used to do our sounds–he phoned up when I was away one time, and my wife answered the phone, 12:30 in the morning. He said, “Elaine you’ve got to tell Mac, we’ve got to get the Bunnymen together again.” He said, “I’ve been listening to old, live tapes; they’re the best band in the history of time.” When she told me, it started me thinking–I couldn’t stop thinking about it. And everything was exciting, like making a cup of tea–I just thought, Fucking hell. And I realized–it’s like my best friend or something, the Bunnymen.

LM: It’s part of your identity.

IM: Yeah, it’s the way I express myself in artistic terms. You know, I can express myself in whatever way, whether it’s to channel that into something important or something good. It’s Echo and the Bunnymen, it’s really important. And it is funny ’cause people say, “Oh, bands should only last for so long.” What you don’t get is that if you start out with a band that’s teenage angst and rock and roll whatever, clichés–or born-again Christianity and cowboy hats–then I do think you sound a bit foolish when you’re singing about kinky boots and all that stuff. But if it’s a name as strange as Echo and The Bunnymen, that’s not necessarily a band name, that’s a banner or something. And that’s the difference, I think. You know, I don’t think of Lou Reed and The Velvet Underground as a 21-year-old. I think of him as Lou Reed, 40-year-old. I’m the same with Leonard Cohen, who’s never young. It’s less about the age. It’s what he’s delivering and what it conjures up. With The Beatles, I can’t imagine John Lennon being younger than 30, ever. And I think that’s a great thing.