EXCERPT

How Sista Grrrl Riot Made Room for Black Queers in Punk

“Black Punk Now,” edited by Chris L. Terry and James Spooner, takes a wide-ranging look at the underground history of Black punk music through interviews, fiction, illustrations, archival photos, and comic strips. The following excerpt tells the story of New York City’s Sista Grrrl Riot, an early, vital Afro-Punk movement. “Black Punk Now” will be published by Soft Skull Press on Oct. 31.

———

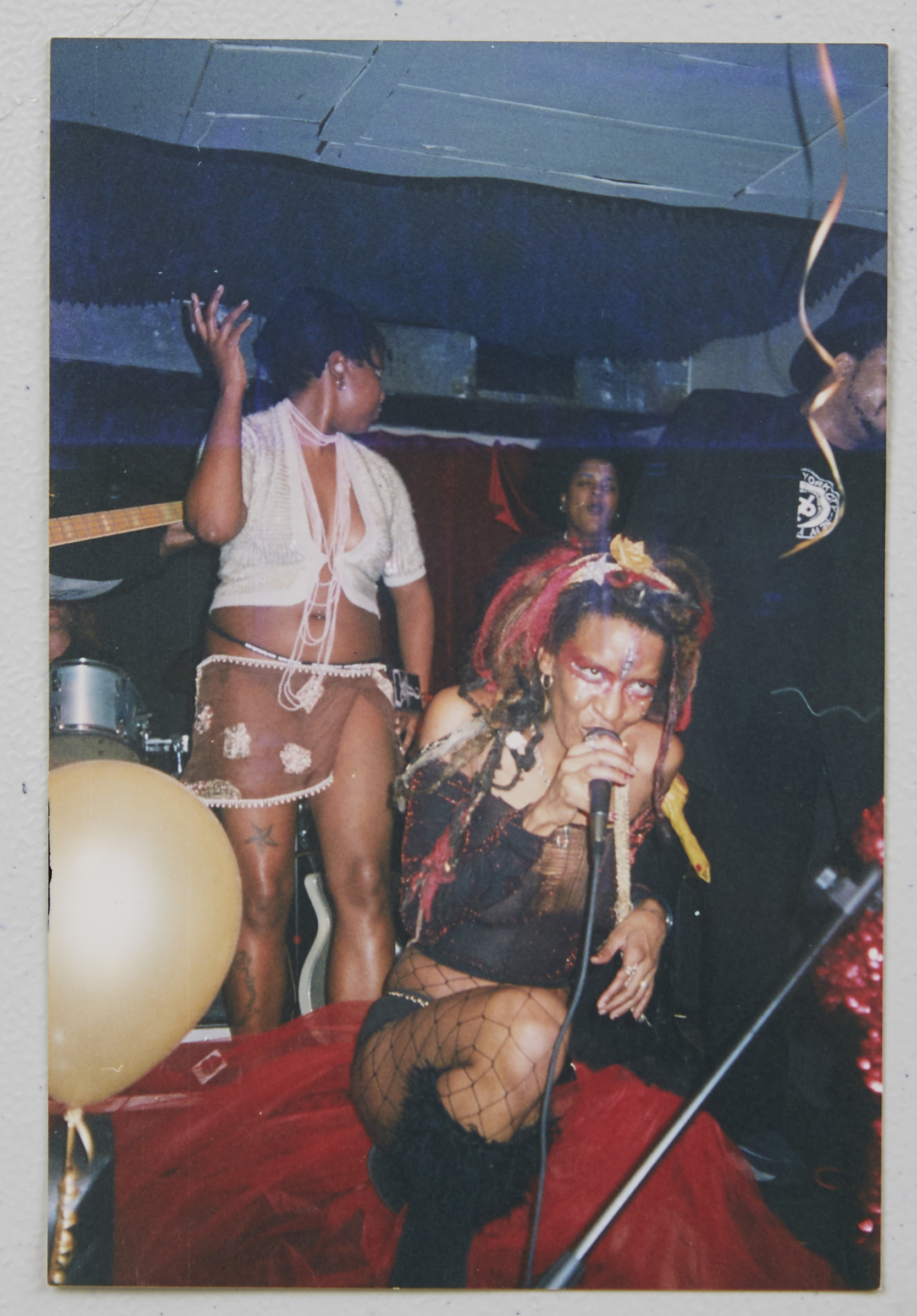

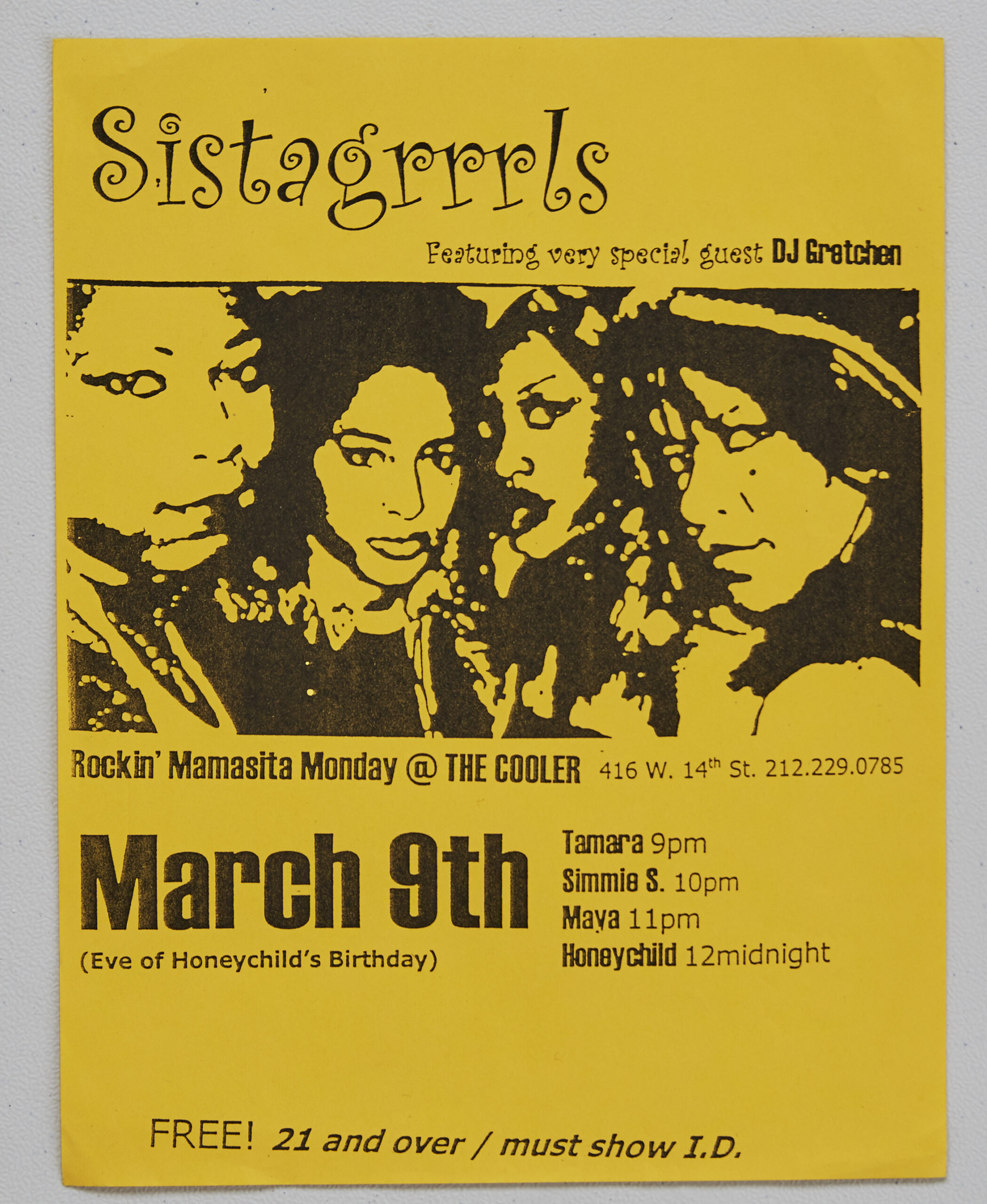

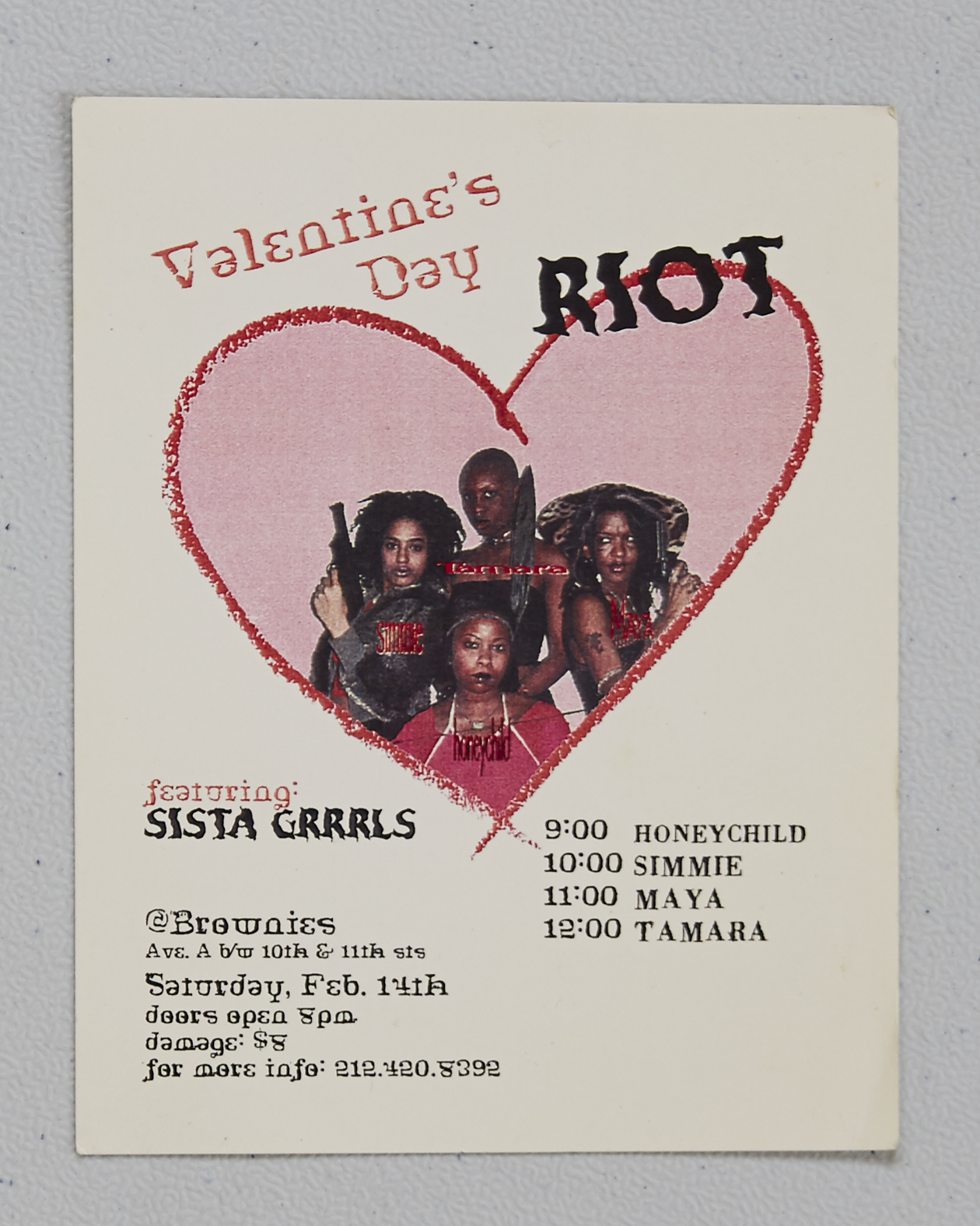

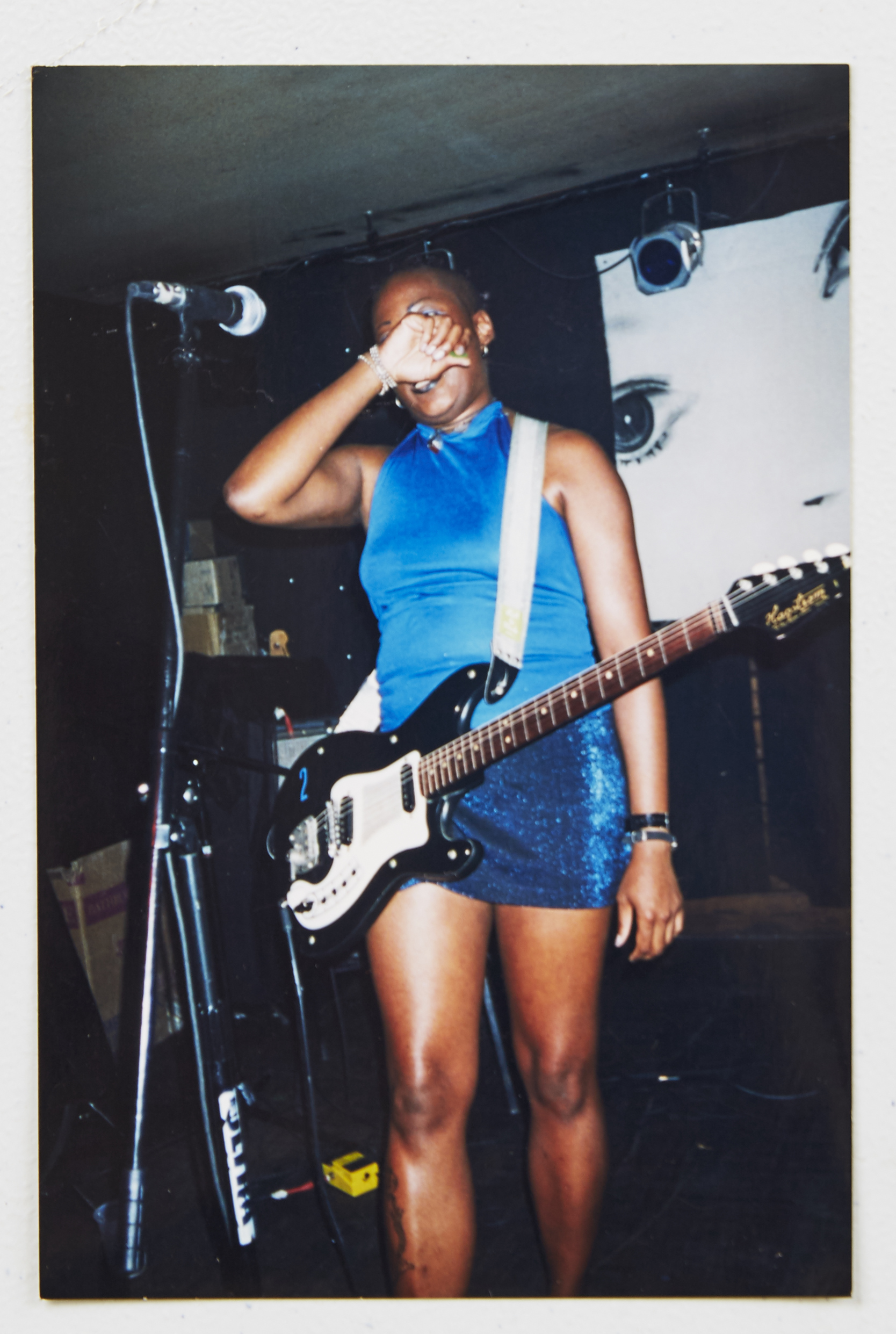

Starting on Valentine’s Day, 1998, New York City-based musicians Honeychild Coleman, Tamar-kali Brown, Simantha M. Sernaker (a.k.a. Simi Stone), and Maya Sokora produced a series of concerts under the moniker Sista Grrrl Riot. Using their connections to New York’s indie music venues, they took turns producing shows, creating flyers, and arranging each evening’s festivities, resulting in an “Afropunk” space before Afro-Punk existed.

Since there is a desire to mythologize the past to make sense of the future, there have been rumors and innuendos over the years regarding what Sista Grrrl Riot was about. To be honest, nothing has come close to the magic this collective produced since then, as the amount of Manhattan-based live music venues has shrunk, and those that survived through the 2008 economic collapse, gentrification, and the COVID-19 pandemic are not as socially, culturally, and racially diverse as they should be in a bustling, cosmopolitan city. So, while all the women have gone on to advance their solo careers, they agreed to sit down for a group chat to talk about what it was like being young, Black, and ambitious creatives who carved out a space to define themselves and their music on their own terms.

———

How did you meet?

Honey C: I want to say we met in ’96. A friend had met and invited Tamar-Kale over for dinner. We saw you walk in and we’re like, “Yo, there’s a really cool woman in here. Let’s go steal her out of the kitchen.” And I remember thinking, “Damn, she’s cool.” When I met Simi, she had a pack of cigarettes in the strap of her bra, a black lace bra on and boxer shorts rolled up like hot pants, with a violin.

Tamar-kali I happened to be playing a gig at Brownies [a former rock club in downtown Manhattan], and Simi was one or two acts before me, and I was transfixed, and I was like, “Who is this girl, breaking my heart with the fricking violin?” I had previously met Maya through my brother [collaborator], Jerome, who played with me, and he was telling me all about her. When I first saw her play live, I rushed the stage like a maniac to get to her.

Maya: Really, you know? And you did. You looked angry. And then I remember after the show, you were threatening to beat my ass . . .

Tamar-kali: Because you did the damn thing. That’s how we do.

Maya: That was your introduction to me. I know. I was like, okay, how fucked up is this post-hardcore New York energy? It’s hella aggro. Like, are we going to fight or fuck? Like, what’s going to happen here? I just needed to know.

Honey C: Yeah. And that’s when I met you [Maya] because she had also been telling me about you. She’s like, “No, there’s this sister. And she is like the punk Betty Davis. And she’s out there, and I just need you to come and meet her, come to this other show.” So, I get to the show, and Simi’s onstage. I knew half of her band, and I was like, “Wait a minute, these dudes like rock.” I was just like, whoa. Everybody in here is Black–”Where am I right now?” Because I’ve been to Brownies hella times through these electronic dance parties and never seen any of us in there. So that was a life-changing night.

Maya: And that was where we converged. That was my first time seeing Simi, and that was my first time meeting Honeychild.

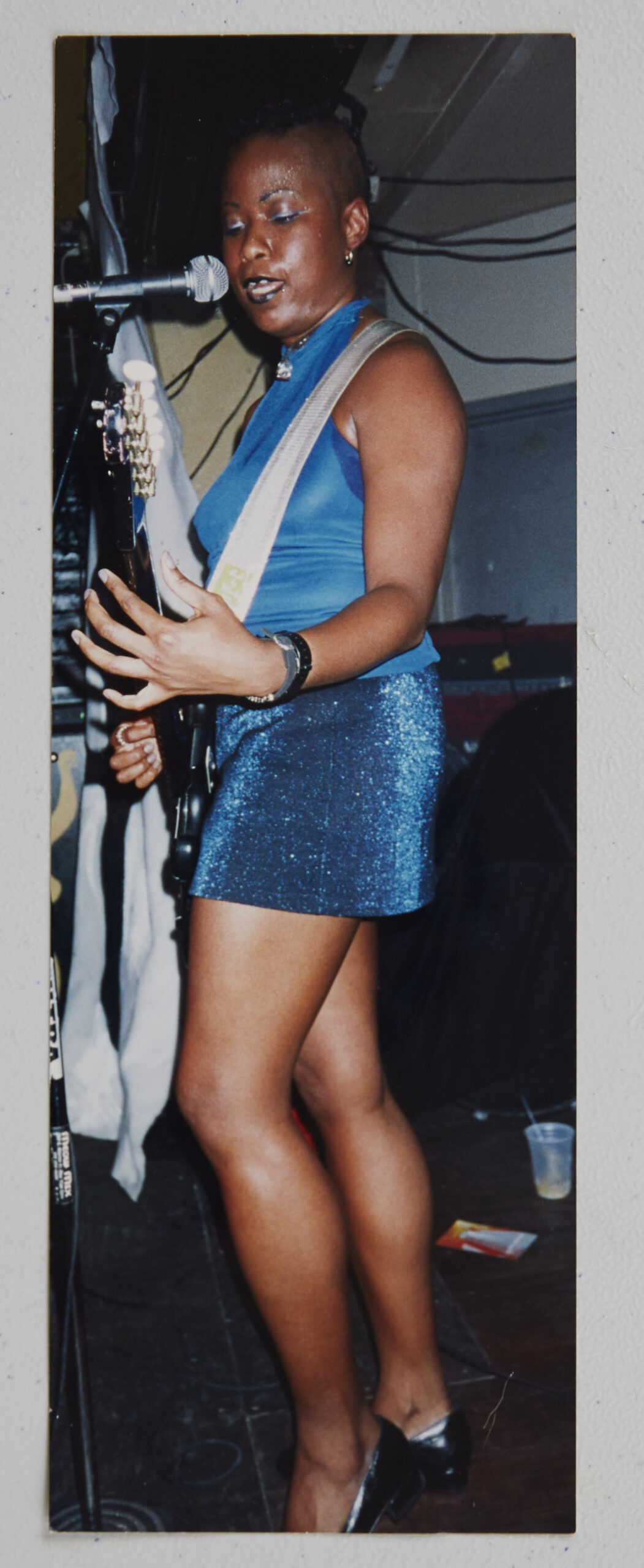

Simi: I remember the first time seeing Maya play with that electric guitar. We were like these Black girls, and we were all stylish in our own way, and we were good at our instruments and songwriting. Was that what connected us? Yeah.

What were the things that you talked about on how to arrange a show with the four of you?

Tamar-kali: Well, we were all women who were booking our own shows, writing our own music, doing whatever. So, when we have the meeting, I remember being like, Look, I don’t know anybody. So why don’t we, like, come together on some show shit? I booked the first one at Brownies or whatever, I had a connection. Maya did one at Webster Hall. I did one at the Cooler. So it was that kind of situation where it was like, we’ll pull things together. Me and Honey C. come from that DIY punk rock background. So, we’re like, “We’re not going to call them shows. We’ll call them riots,” and any riots I threw, I did the flyers. Same with Maya. Same with Honey C. See, that’s the way we rolled. I think Simi, at that time . . . you were probably the only one to have ended up with a manager.

Simi: I did end up with the manager and a band of men, all boys. But I feel like he was pretty down with what we were doing.

Tamar-kali: For the most part, the shows were very much steeped in that punk rock DIY ethos.

How did your shows get advertised?

Tamar-kali: Well, everybody had their own fans first, so, like, we were doing that thing already? Whoever produced the show, you know, they were, like, the producers. So, they were paying the cost to be the boss. They were handling the door, doing the splits or whatever, and they would give us the flyers to distribute.

Simi: It was phone calls, and it was word of mouth, and we sold out CBGB, you know, like it was packed.

Tamar-kali: We were in New York. We were doing our own thing and had our own fan bases. Then, because of the spectacle of all four of us being on a show at the same time, [we] attracted other people and namely other Black women who were curious about the Sista Grrrl Riot show, whereas they might not have felt safe or comfortable before.

Simi: We were really pushing that our shows be safe spaces.

How did you feel within these spaces in terms of your physicality on stage because you were sharing the stage with three other women? Did you find that these performances were liberating to you personally, sexually like in terms of expressing yourself on stage?

Simi: Hmm. Well, I mean, I grew up in a place where there were a lot of beautiful women around. I never felt like I was like the sexiest person, or the prettiest person, because I just wasn’t. I was kind of a dork, and everyone was so cool. So, the beauty of working with these three was so inspiring, and we were all so different in our sexuality, I don’t feel like there was a lot of pressure; I used to wear, like, nothing, though I know we were in our twenties.

Tamar-kali: Yeah, I was on some fucking, like, queer feminist shit, like, you know, I might be under some nipple shields in a black shirt, but I felt so comfortable at that time. What I was, was what I felt like philosophically, and I think you’re very idealistic when you’re young as well. But meeting with these women, I felt like I could be my full, pure, unadulterated self. And it felt so good. But then the problem was that, because of us coming together in certain ways, the spectacle of us brought energies from the outside that were not aligned. It was a beacon for people who were like us. But then it also was the spectacle that whenever there’s a buzz in New York of any sort, the things that people draw people in. People started coming to see what shenanigans were going to happen, like, who was going to get naked? That, to me, turned it into something else.

I know that when people think of, let’s say, black women and rock and roll or punk or hardcore, there’s always this “Ooh, that sounds sexy.” And they think that there’s this sexually subversive thing going on because they’re not used to seeing Black women playing rock or anything heavy. DId you get any type of vibe from people kind of, like, fetishizing you because of your image versus the music you were playing?

Tamar-kali: Then there were some weirdos at a couple of shows. There were some total weirdos. Some thought we were into necrophilia, and we got some fetish-types there. We probably could have done a whole record beating people’s behinds because there was some truth in that.

Simi: I don’t ever remember feeling scared. I was trying to be a white boy, like a thin, sexy white guy. I was like, those are the people that played punk. I wanted to be like that. I didn’t want to be like Belly or like any of those like chicks. Sorry, but those softer women, those ’90s girl bands, which had no Black people in them.

Maya: You know what it is? Here’s the thing about sexuality in music and what was different with us, and maybe why we attracted freaks or whatever: I didn’t notice that with our thing because it was already there. But here’s the thing that’s different: Music and performing on stage was, and still is, for me, a literal act of intercourse. It’s intimate and there is this energy and sweat and it’s powerful. And I think that’s true with a lot of artists. You’re sharing this intimate part of yourself, you’re opening yourself, you’re naked in a lot of ways. But I think that with women in music, that sexual energy that complements women is submissive and they’re opening themselves very softly to be dominated or to be the soft flower in some way. And that’s fine and it’s lovely and beautiful. But I think the energy with the three of us was different and we are all dominant people. I remember that some of the bands, some of the musicians who I still love very much, had a hard time with me not letting them take over the production of the songs. They had a hard time taking direction from me. And it was my music because my music was very three-chords simple, and I played with badass musicians who would be like, “Okay, so she gave us the chord structure? I’m just going to run with it.” No, don’t run with my shit.

Tamar-kali: And that’s the beauty of us coming together, right? Because it’s like we could have a soft place to land. Everybody understood what we were going through. It wasn’t a mystery. It’s like you try to have these conversations with people and they don’t, they really don’t understand. They don’t understand how you’re a musician. You have your credits, and you have your experience, and folks are mansplaining to you all day, even if you know they are undermining you. Your name is on the marquee, but the sound person wants to talk to everybody except you.

Do you think that these performances changed the perspective about Black people performing punk music?

Simi: Yes, yes.

Tamar-kali: I don’t know about punk, but I tell you, what I would venture to say is that the landscape of the downtown music scene where Black folks were concerned looked a lot different after us.