excerpt

Geoff MacCormack Looks Back on His Lifelong Friendship with David Bowie

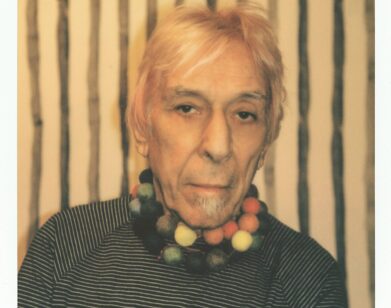

Songwriter and producer Geoff MacCormack met David Bowie as a primary school companion, but their shared love for music made them a lifelong inseparable pair. In this excerpt from his recent photographic memoir, David Bowie: Rock ‘n’ Roll with Me, published by ACC Art Books, MacCormack revisits the particular period in the late 60s when Bowie’s march to fame began.

———

Haddon Hall: The Beginning of Success (1969–1972)

Madame George’, Van Morrison, 1968

Thanks David for introducing me to the divine album “Astral Weeks.”

In 1969, David had moved to a fantastic Gothic, raised ground-floor flat in Beckenham with his girlfriend and soon-to-be wife, Angie. Haddon Hall was one of many grand Victorian and Edwardian houses built in the suburbs of London for the wealthy who wanted more space as well as easy access to London. I lived in such a place from the age of 12, when my family moved from Bromley to Beckenham, until I left home for West London. My mother’s house was at number 1 Blakeney Road, about a quarter of a mile from where David and Angie were going to live.

Haddon Hall was an extremely grand double-fronted abode, and the area David rented had a magnificent hall with stairs that led up to a double-sided gallery from where Joan Crawford would have been entirely happy to have descended. Unfortunately, the gallery didn’t actually go anywhere as it was boxed off to create more apartments, but there was enough room to sleep around the balcony, which many people did. Some of the most important balcony guests were three musicians from Hull, Mick Ronson, Woody Woodmansey and Trevor Bolder, later to become the legendary Spiders from Mars.

I remember David introducing me to the wonderful Astral Weeks album by Van Morrison around this time, which seemed a perfect backdrop to the interior of Haddon Hall. I would come down from where I had moved to in Bayswater, London, and visit David at the Hall, sometimes in ‘The Rosko International Road Show’ truck, which always amused him.

David’s musical output seemed to be really prolific around 1971 following his ‘Space Oddity’ hit, which peaked at number 5 in the UK charts at the end of ’69. The follow-up single ‘Holy, Holy’, however, didn’t fare so well, and it looked like David might not repeat the success again. But he was writing all kinds of stuff in all kinds of styles; he even wrote a song about his car called ‘Rupert the Riley’. It’s a wonder that he ever mentioned his Riley (a 1932 Gamecock) since the bloody thing nearly killed him. It happened like this: he was trying to start the beast by cranking it into life the old-fashioned way, with a starting handle at the front of the car; problem was, he’d left the old pig in first gear. As he turned the handle with a mighty effort, the thing lurched forward and pinned him to the vehicle behind, just missing the main artery in his leg. Luckily, he was right outside the police station in Lewisham where the cops who had been laughing at the long-haired idiot trying to get his old wreck going, jumped into action with their first-aid kit. George (Underwood) and I went to visit him in Lewisham Hospital a couple of days later. On seeing his pale, sad little face, we burst into a chorus of Clarence Carter’s song ‘Patches’, which goes ‘Patches, I’m dependin’ on you, son, to pull the family through, my son, it’s all left up to you’. I remember he gave us an ironic smile, the kind of smile one might reserve for your oldest friends after you’ve run yourself over in your own car.

David wrote, or allocated, songs for everyone around him, as if he were on a journey and wanted to take us all along. This was also David’s ‘Li Li, La La’ period. He wrote a song for me (‘How Lucky You Are’), which ended with ‘Li Li Li Li Li Li Li Li Li’. He also wrote a song for George (‘Hole in the Ground’), which started with ‘Li Li Li Li Li’. Even the song ‘Time’ ended the same, admittedly two years later. One could argue that the most rewarding moment of this ‘Li Li, La La’ period was the ending of his ‘Starman’ appearance on Top of the Pops in July ’72, which would launch him as a star.

David wrote a song for Freddie Burretti as part of the Arnold Corns band project, and the song ‘Andy Warhol’, for the singer Dana Gillespie, with whom David had had a relationship in the late ’60s. ‘Andy Warhol’ was recorded separately by Gillespie and David in 1971 and appeared on her album Weren’t Born a Man in 1973, which was produced by David and Mick Ronson, as well as on David’s 1971 album, Hunky Dory. David also wrote ‘All the Young Dudes’ for Mott the Hoople.

Of all these songs, which were all recorded with us, ‘the artists’, mercifully only a few of them are known to the general public. Mott the Hoople’s version of ‘All the Young Dudes’ was released as a single in 1972, making number 3 and number 37 in the UK and US charts respectively. The Arnold Corns’ tracks later emerged on Bowie’s albums, Hunky Dory and The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars.

Part of David and his generosity was wanting to take his friends on the journey with him. He would invite us to a recording of a John Peel Show at the BBC. He took George Underwood and his wife Birgit as guests on a mini-US tour, traveling on the luxurious liner Queen Elizabeth II. He asked his friend Freddie Burretti to become his clothes designer. And, sometime later, he asked me to become a member of an extended band.

A QUESTIONABLE DEAL

‘Use Me’, Bill Withers, 1972

The reason David had this new freedom to create music without restriction was due to his new management, who had come recommended to him by his label manager at Philips Records. Litigation clerk Tony Defries and show-business accountant Lawrence Myers had recently formed a business partnership, Gem Music Group. To their credit, they not only saw potential in David, but they offered him what seemed like an attractive deal–one that would supposedly alleviate his day-to-day financial niggles, as well as secure his long-term future. And so, they came to an agreement for Gem Music Group to work with the rising star.

I was never really sure whether David completely understood the arrangement Defries was proffering. I don’t know whether he went along with it out of a desperation to get to the level he desired—deserved even—thinking that he’d deal with it at a later stage when he was established, or whether he signed the deal because he was so eager, after all his previous disappointments. Either way, he took his eye off the ball. The deal he signed was basically as an employee of what would become MainMan, Defries’s new company, not, as he may have thought, as a partner. The vague outline of the details in the contract is something I would only discover around the beginning of 1975 when David and I were hanging out in LA, and he was suddenly broke.

Myers involvement with David would last just a year and a half. Defries wanted to open an office in New York where he planned to build a music empire, adding new artists like Iggy Pop and Dana Gillespie to the roster. Some of the new artists would willingly sign, but others like Lou Reed and Mott the Hoople didn’t. Since David’s ascent was being funded with Myers’ own money to the tune of £75,000 (then an absolute fortune) and he was fed up with all the ‘maybe signed’, ‘could be signed’, slightly deranged-looking ‘artistes’ hanging around his offices, he decided to strike another deal with his partner. This gave Defries the opportunity to start a new company–MainMan–taking Bowie and all the other signed artists for the return of his investment, plus a share of future profits up to the sum of £500,000.

When Defries acquired this sum mysteriously quickly (probably from RCA Records), Myers was happy with his quick return and bowed out. This, in time, would reveal itself to be an expensive arrangement for both Myers, who missed out on taking a percentage of David’s future earnings, and David himself, when years down the line in the late Nineties it was alleged that David had to pay around $25 million to Defries for his original masters.

Tragically, years later, in 2012, Defries was to lose it all and more in a $9.5 million lawsuit with Capitol Records, EMI and others. And, allegedly, he lost a further $22 million in an offshore tax-evasion scheme.

Listening to the new management hold court at Haddon Hall was rather like being at one of those Satsang group events that I’d been to with my friend Chris, but without the smell of incense or the yogic positions. Instead, there was always the pungent smell of a Havana cigar which Tony would always be smoking, used as a kind of Churchillian prop. Deep reverence was paid to his every word as if he were the one with the Knowledge, sagely proffering a new wisdom. David would sit quietly listening, with Angie sat at Tony’s feet, beaming like a dolphin at feeding time. I have to admit, even though we didn’t much care for each other, he was a top-draw spieler and he delivered what he said he would.

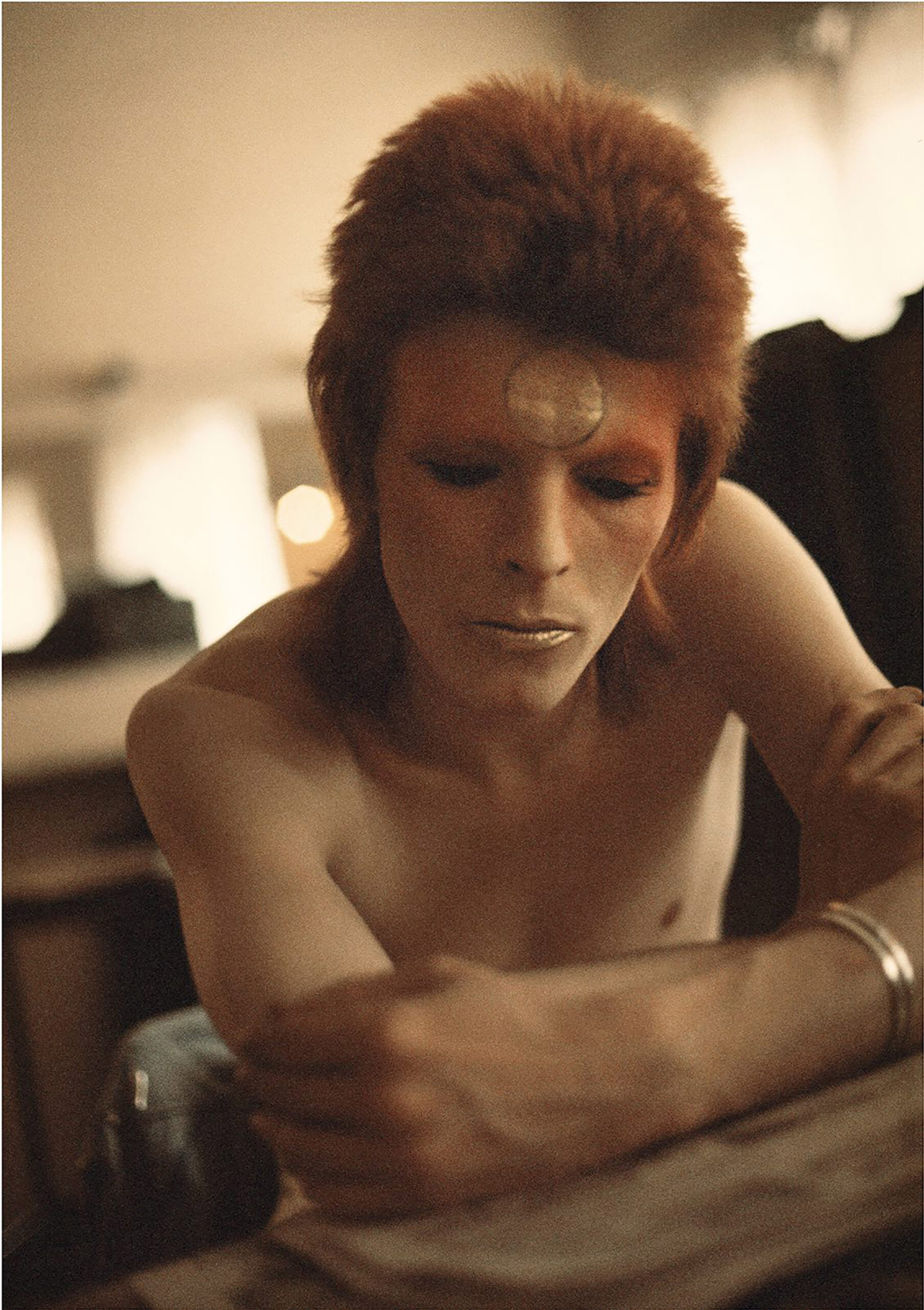

ZIGGY STARDUST

‘Handbags and Gladrags’, Chris Farlowe, 1967

Sometimes my girlfriend, Desna, and I would bring armfuls of clothes from the women’s clothing boutique Feathers down to Haddon Hall for Angie and David to try on. The little nylon fake fur-lined jackets that David (and the Spiders) were photographed in many times at the beginning of the ’70s, at the start of the Ziggy phenomenon, came from Feathers.

Desna was working as a trainee buyer for Feathers on High Street Kensington, next door to Kensington Market. The store was run and owned by the Burstein brothers, Sydney and Willie, and their wives. Sydney’s wife, Joan, later affectionately known in fashion circles as ‘Mrs B’, was the brains behind Browns of South Molton Street, which she started after Feathers in 1970 and which was known for championing new talent. I would sometimes collect Desna from Feathers and I vividly remember this very pleasant, handsome guy who was always wrapping fabrics around Desna’s dainty feet exclaiming, ‘I have this wonderful idea’. A few years later, Diana Vreeland, the editor-in- chief of US Vogue, saw this guy’s portfolio and encouraged him to make things. For Manolo Blahnik the rest, as they say, is fashion history.

When Mrs B left Feathers to open Browns, Desna went along as a trainee buyer. As Browns quickly expanded, they opened a section for men’s wear in the basement. I worked there for a short while until they fired me. Actually, they got me to sack myself by asking me to clean the lavatory. Then it was just a matter of waiting, oh, five seconds, for me to tell them to go fuck themselves and, hey presto, I was gone. I then got another unsuitable job at the men’s boutique Mr Fish on Clifford Street. Neither of these positions were thought-out career moves, just fill ins.

David or Angie (or both) had been talking about men’s dresses and during my short stay at Mr Fish I noticed, tucked away, this small rail of heavily discounted men’s gowns. I knew of only one man in London who might be interested in this un-repeatable sale, and he lived at Haddon Hall.

When I called David, he was at Mr Fish’s boutique in record time which, strictly speaking, was unnecessary as the garments had been languishing there, unsold, for quite some time. David tried a few of them on and it was as if they’d been made for him. I expected Mr Fish to be at least pleased, but he stood there impassively, almost bored, and not even Angie’s squeals of delight made a dent in his demeanour. Perhaps he had realised that the Mr Fish bubble had well and truly burst. However, I’d like to think that somewhere down the line Mr Fish, while browsing through some albums, came across David Bowie reclining on a chaise lounge wearing one of his creations on the album The Man Who Sold the World and that a wry smile registered across his handsome face.

David and Angie’s son, Duncan Zowie Haywood Jones, was born in May of 1971, a joyful occasion which prompted the writing of the song ‘Kooks’, which appeared on Hunky Dory. The song’s debut was heard on the BBC in Concert in June with John Peel. David, who was in great spirits enjoying the birth of a son and a new-found productivity, was in celebratory mode; not ‘let’s get loads of booze and have a piss up’ but ‘let’s all bowl down to the BBC and celebrate on the air waves’. The show was cobbled together by David at Haddon Hall in a very short time and, as well as the Spiders, friends and neighbours were all invited along to do a bit: Dana Gillespie, George Underwood, Mark Pritchett from across the road from David at Haddon Hall, and me. John Peel announced me as Geoff MacCormack, who lives down the road. The whole affair was to become part of Bowie at the Beeb, a compilation album which was released in 2000, nearly 30 years after the sessions. To say it was loose would be an understatement. We sang the Ron Davies’ song ‘It Ain’t Easy’ together, with varying degrees of hilarity; David sounds slightly crazy, I sound like my mouth’s full of cotton wool, George sounds completely crazy.

Another even weirder happening later in the year was the arrival from New York of the stage play Pork at the Roundhouse in London. The play was loosely written by Andy Warhol and New York writer/director Tony Ingrassia, with a cast including The Factory personnel Geri Miller, Tony Zanetta, Wayne (Jayne) County and Jaime (de Carlo) Andrews, with photography and stage management by Leee Black Childers. I really don’t remember much about Pork except that it was rather silly and had lots of nudity. David became friends with some of the cast who would later be recast by his management at MainMan in various new roles such as ‘president’, ‘vice president’, ‘tour manager’ or ‘office managers’, as they became part of David’s crew and entourage until the mid-Seventies. I must say, I very much liked the cast of Pork, especially Cherry Vanilla, who was fabulous fun, and dear Leee Black Childers, who was perhaps the sweetest of them all.

The year 1972 kicked off with David’s 25th birthday bash at Haddon Hall. Lionel Bart was one of the guests and it was the first time I’d seen him since the old Mod days in Soho when he used to float about with a posse of good-looking young men in tow; he was very charming and friendly. Lou Reed, who was also in attendance, had met David in New York in September the year before. He and David sat together for most of the evening in an exclusive club of two, while Angie was the perfect hostess flitting from one person to another making sure everyone was happy. David looked in great shape with a new short haircut and what would become the Ziggy look. I think we all ended up at El Sombrero nightclub in Kensington.

That year would turn out to be the busiest and most grueling schedule for David so far. He finished recording and released The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, produced Reed’s album Transformer, completed a 29-date tour of the USA, mixed Iggy Pop’s Raw Power album, sailed both ways across the Atlantic, wrote and recorded Aladdin Sane, did press and TV appearances for an album and four singles, and collaborated with Lindsay Kemp, putting on two major shows at the Rainbow Theatre in London.

I was living in Notting Hill by 1972, when David’s new single ‘Changes’ popped up on the radio. This was incredibly exciting, not just because it was David but because it was a piece of music that was so different, yet at the same time so accessible. The fact that the album it came from, Hunky Dory, (December ’71) also had ‘Life on Mars’ and ‘Oh! You Pretty Things’ made the album, to my ears, both contemporary and original, while ‘Queen Bitch’, a harder, rockier sound influenced by the Velvet Underground, linked beautifully to his next album The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars. A year for great album releases – from Stevie Wonder, War, Neil Young and the brilliant Bill Withers album Still Bill—1972 also saw three albums directly related to David’s output: his own, Ziggy Stardust, and producing Lou Reed’s Transformer and Mott the Hoople’s All the Young Dudes.

Towards the end of 1972, David started to record his follow-up album, Aladdin Sane, at Trident Studios in St Anne’s Court in Soho. I somehow ended up doing some backing vocals, which I no doubt did for a laugh and probably didn’t even bill for them. It was like ‘just helping a mate out’ kind of thing. Apparently, I also did the percussion for the track ‘Panic in Detroit’. My memory isn’t clear on any of this, which sounds crazy to most people – I mean, how can you forget working in Trident Studios with David Bowie?! I can only suppose that because I wasn’t a session man, it was all a bit, well, casual.

However, knowing the songs and arrangements on Aladdin Sane at the recording stage must have put me in good stead later when David wanted to expand his sound for the 1973 tour.