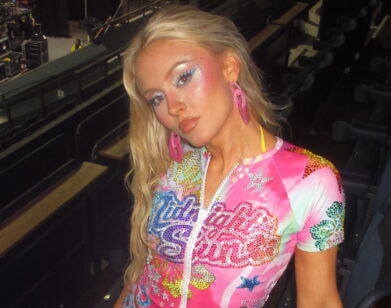

Exclusive Song Premiere and Interview: ‘Lip Gloss Anthem,’ Sega Bodega

ABOVE: SEGA BODEGA. PHOTOS BY MARTIN D. BARKER, TAKEN ON LOCATION AT GLASGOW BOTANICAL GARDENS

Scottish music is just bagpipes to a lot of us in the rest of the world—and if you were to take a trip to the Edinburgh Festival this year, there’d be plenty of kilted pipers vying for tourist change in the streets, doing nothing to help shift stunted stereotypes. But there’s been a progressive music scene coming out of Scotland for years. The School of Art in Edinburgh’s neighboring Glasgow has sent alumni bands like Orange Juice and Franz Ferdinand out of their halls and onto the international stage, making Glasgow a citadel for creatives that has given the post-industrial streets a Williamsburg-style makeover.

In recent years, the city of Glasgow has become a hub for progressive electronic music. Native producer Hudson Mohawke set the pace with a unique sound that combines Gaelic gloom, space-age R&B, and hip-hop, gleaning the favorable attention of Kanye West, among others. Salvador Navarrete, aka Sega Bodega, is the Glaswegian beatmaker who’s continuing in the great tradition of his innovative countrymen. He’s been on remix duty for the likes of Jakwob and Lana Del Rey and has also featured live alongside SBTRKT and Julio Bashmore. His debut EP, 34, is an intricate release that shows off the myriad facets of his eclectic influences. Rich cinematic sweeps and Atari bleeps are central to his esoteric audio mix, which never strays far from the dark, gritty streets of his stomping ground. We spoke to Navarrete via Skype and talked sights, sounds, and serial killers.

DOMINIC MAXWELL-LEWIS: So you just shared a bill with Mykki Blanco. How was that?

SALVADOR NAVARRETE: It was pretty amazing. I was on after him, so I got to watch the show.

MAXWELL-LEWIS: Oh yeah?

NAVARRETE: Yeah, the energy he had was insane. It’s really good to see something happening like that in hip-hop.

MAXWELL-LEWIS: What kind of reception do you get in London compared to Glasgow?

NAVARRETE: I don’t know. I’d say that compared to Glasgow, audiences are just… calmer.

MAXWELL-LEWIS: Scottish crowds are pretty wild, from what I hear.

NAVARRETE: They’re fucking crazy.

MAXWELL-LEWIS: What’s the craziest thing you’ve seen at a Glasgow show?

NAVARRETE: The other week at this club called Make Do, a guy tried to take a shit on a speaker, but that’s about it. It’s not usually just single events like that. Just the overall vibe of a big night out in Glasgow is intense. It’s so good.

MAXWELL-LEWIS: Let’s talk about your sound for a second. There’s so much going on, but there’s a definite cinematic quality in your music. Have you considered scoring films?

NAVARRETE: That’s what I’d love to do. A big, orchestral Hollywood style epic. My favorite thing to do to pass the time when I was bored on the Internet was to find scenes from films that don’t originally have music and add music to them, whether it’s mine or someone else’s. I found I could accentuate these amazing moments. So I’d say it’s something I’d 100 percent like to do in the future.

MAXWELL-LEWIS: Let’s talk about your influences. I heard elements of so much in 34, from Tetris to Balearic house.

NAVARRETE: I make electronic music, and I know that. But even within that, I really hate how everything in the genre is so quick to be on to the next one. It’s just getting the youngest, hippest producers and throwing them on everything, and they blow up within months. I don’t want to be a part of that. I think it’s because I hate so much of it that I do what I do.

MAXWELL-LEWIS: So you think electronic music is more about the “scene” than the music?

NAVARRETE: It’s just something that bugs me sometimes, when I see producers who were making dubstep two years ago who are now making garage stuff or Disclosure/Cyril Hahn stuff now. I’m not saying it’s a bad thing to evolve, but to do it so drastically makes me kinda think it’s not so much about music, but more about being “with it.” I just hope the music isn’t going to be dated in six months’ time. My biggest influences honestly are probably HudMo and Rustie.

MAXWELL-LEWIS: What about Hudson Mohawke and Rustie? I mean because of the success of those guys plus the labels Numbers and LuckyMe, do you think that there are higher expectations for people coming out of Scotland?

NAVARRETE: Yes, absolutely. The thing about them that I like is that they never really “blew up.” They’ve been around since 2005. They just arrived over time at where they should be. But there was never a point at which it suddenly just happened. I mean even today when you play Hudson Mohawke’s track “FUSE,” people just go crazy.

MAXWELL-LEWIS: Do you think Glasgow is a more innovative place than others?

NAVARRETE: I think so. It seems as though when people start something here it’s just so different.

MAXWELL-LEWIS: Less constrained?

NAVARRETE: There just don’t seem to be any rules to it here. It just is what it is, and you can’t explain it.

MAXWELL-LEWIS: You shy away from genres; why’s this?

NAVARRETE: That’s because these days no one has a clue how to name the genres they’re listening to anymore. The only way we’re going to get past these flavor-of-the-month names, like trap or whatever people feel like naming stuff at the moment is by keeping it simple. If we just call it electronic music, then we’re all safe.

MAXWELL-LEWIS: While we’re on the subject of names, the titles of the tracks on your EP are pretty intriguing.

NAVARRETE: Well, Konerak and Tuomi are actually the names of people who were killed by Jeffrey Dahmer. You know who he is?

MAXWELL-LEWIS: The serial killer?

NAVARRETE: Yeah. He tried to bring people back from the dead and eat them and loads of really insane things; but this Konerak guy was 14, and Jeffrey Dahmer drugged him at a bar and took him back to his place, but he woke up and escaped. He was running down the street naked with a smashed-in head, and found some police; but Dahmer found him and convinced the police he was his boyfriend, so they released the kid back to him, and within an hour he had been chopped up and his head put in a freezer. [pauses] And it’s a really nice name too, Konerak.

MAXWELL-LEWIS: So you’re drawn to the darker aspects of life?

NAVARRETE: Serial killers are my favorite thing. You can watch so many documentaries on them and they’re just these fascinating, unique characters.

MAXWELL-LEWIS: I guess so. You lived in Barcelona for a while, did that bring any sunshine to your music?

NAVARRETE: No. [laughs] The main reason I moved back to Glasgow is because I didn’t do a thing while I was there. I finished I think two songs in six months. There was just so much else to do.

MAXWELL-LEWIS: So you’re a creature of your environment. Do you need your home surroundings to create?

NAVARRETE: Yeah, I think I just need to be in a place where there isn’t much going on as well. I think the only reason I can sit down and make a song is because there’s generally not much going on here during the week.

MAXWELL-LEWIS: So your process involves not being distracted in a place that isn’t distracting.

NAVARRETE: Yes, absolutely.

MAXWELL-LEWIS: Just quickly, your song “We Don’t Know What Sexy Is” is a big statement. Who do you think makes sexy music?

NAVARRETE: Bondax make sexy music. They’re focused on making really slow, smooth beats. They’re sexy.

SEGA BODEGA’S DEBUT EP, 34, IS OUT NOW ON WEEK OF WONDERS. FOR MORE ON THE ARTIST, VISIT HIS FACEBOOK PAGE.