This electronic pioneer thinks we’ll eventually beam music straight into our brains

This year marks the astonishing 50th anniversary of the release of Morton Subotnick’s landmark Silver Apples of the Moon, one of the first electronic albums commissioned by a record company and also one of the first to break the top ten on the album charts. Affectionately referred to as “The Godfather of Electronica,” Subotnick was heralded as an innovator, using a Don Buchla-designed synthesizer—in 1967, an outlandish piece of musical equipment—to create not just a new music, but a new approach to music. This past Friday, Subotnick performed the piece to a rapt audience at NYU’s Skirball center. It sounded remarkably fresh and contemporary, in line with the abstract, modular electronic music that’s currently in vogue with labels like Warp or Spectrum Spools.

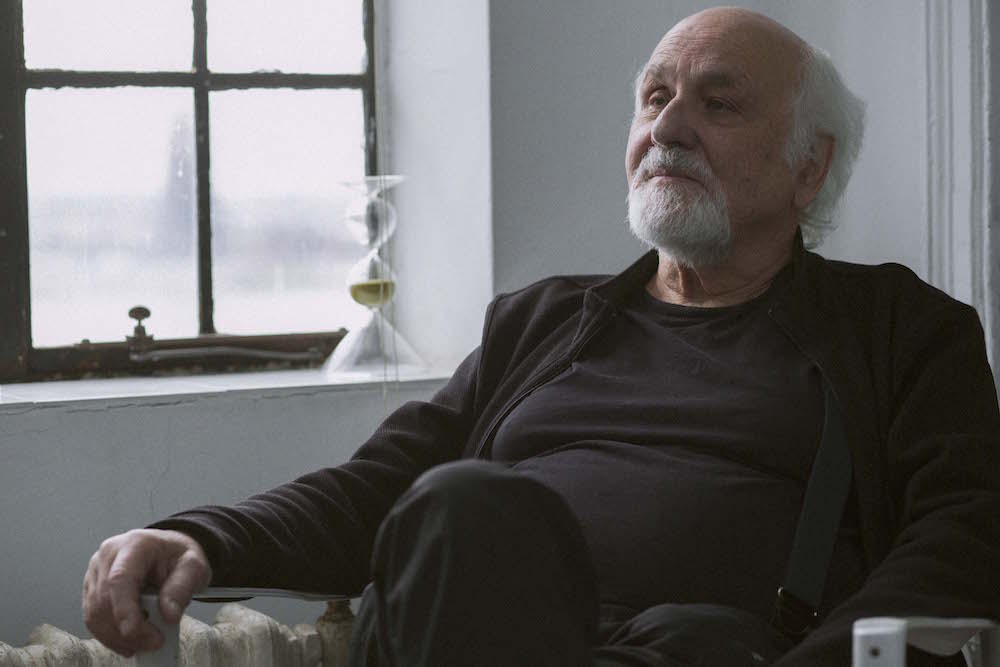

Silver Apples of the Moon is a record that will be forever linked with discovery: for listeners in 1967 discovering alien worlds; for listeners now, discovering that breakthrough moment frozen in time; for Subtonick himself, now 84, discovering the potential of new instruments and new mediums. It is the gold anniversary of the album that brings us together in his Tudor City apartment last week. As Subotnick will imply throughout our two-hour conversation, it is the context of the work that makes it so important: that moment where he turned his back on the clarinet, the keyboard, and his classical tradition, to forge something wholly new.

DALE EISINGER: Tell me about some of the changes you’ve seen in how music is made and consumed over the last 50 years.

MORTON SUBOTNICK: You used to be able to say that music reflects the kind of general metaphor of the period. For instance, the tonality of 18th-century music is Newtonian physics. It’s this balance of everything balanced against something else. They saw the universe that way. There’s not one person now, there’s not one group of people, who sees the world that way in a single metaphor. You can’t get a single metaphor for the world! An exercise I give to students is to sit at the end of the day, where you can see the horizon, and watch the Earth go up. And you can do it, but you have to know that the Earth goes up, that the sun is sitting still, and we’re going this way! [laughs] It wouldn’t occur to you to even do that unless you knew that.

I give a lecture called The Transistor, The Tape Record, The Credit Card: The Technological Big Bang. That to me was the moment to music to what the printing press was to language. Before the printing press, to read a book, you had to go to Alexandria, Egypt. And they would take three months to a year to copy one book. So most people didn’t read. They were not literate. Most people didn’t hear music, they only heard the music that was near them. So if they lived in the Ozarks, that’s the kind of music they would hear. If they lived in Berlin, they would hear historical music. So the difference between the person growing up in the Ozarks and the person growing up in Berlin or New York was huge. One was literate and one wasn’t. In China, I think up until relatively recently, villages, if you got a letter, you would bring it to someone who read, and they would read the letter to you. So it didn’t exist before that movement, the literacy, the potential for literacy, and that grew much faster than I expected.

What does it mean that an 18-year-old kid could play at Carnegie Hall? What does it mean to their life at that point? It means that they played the piano or violin or whatever it is, from the time they were four years old or five years old, that’s all they did. I played the clarinet, in high school. I played a concerto with an orchestra. By the time I was in high school I was playing professionally in Los Angeles. But up to that point, up to high school, I spent an average of two to four hours a day practicing. And by the time I was a junior in high school, I was spending two to four hours learning music theory and music history and beginning to write music. So if that’s seven to eight hours a day, that means I slept in school, because I had to get up really early to do it, and I didn’t do much else. I lived this life! If you did a normal life, you wouldn’t have been doing that. You would be in baseball and football and going to parties and going to the movies and doing all these other things. So when the time comes, and you’re 18 to 19 years old, there’s no way you’re going to play a concerto with an orchestra, and there’s no way 90% of those people who get there are going to do anything else with their lives.

These trajectories branch out and meet on the street and say hey how are you, but they just go. Now we have histories of genres of dance music that just keep coming out. We still remember disco, but we have these other things. What we get is an infinite number of trajectories. The metaphor for me, the 20th century metaphor, the main philosophic concept for the 20th century was existentialism, right? The science was relativity and the music was twelve-tone. There were a lot of others, but those were the ones that maintained their hold. So we had a single metaphor. What fucking metaphor do we have now? Do we have a single metaphor? Yeah, it’s quantum: you just don’t know. And we’re comfortable with that. We’re saying, I don’t know what’ll happen if such-and-such happens. We don’t know and we’re comfortable. No one was comfortable with that when I was growing up. You had to know because it was going in one direction. We had to know where we were going! What’s your goal? I don’t know, I’ll know it when I get there. The multiplicity itself, looking from the outside, may be the metaphor.

EISINGER: What do you think is the future of music?

SUBOTNICK: I think of it like the Dr. Scholl’s foot pad, when you step on it, it kind of oozes out. [laughs] The present is kind of oozing out a little tiny bit of the future and a lot of the past and around it goes. Every step you take is a step into the future. But the past is huge. But you don’t know anything about the past except what you know. The past exists only in the present, you only know what the past you and present you know about. We learn about things and then they become part of the present.

Now take this and smoke it: in your lifetime, and maybe even in my lifetime, you will see the edge of the Big Bang. You will see it physically, a picture of it that will be taken by something. And everyday when you look at the stars you’re looking at things that have been there for a billion years. So it’s in the present, but it’s been dead for a long time. So if you don’t comprehend that, when you think about history, if you think of history as a linear thing, a bunch of events that led up to something, then you could trace it. But that’s really limited in terms of this understanding. So if you understand that we’re living in the future of that star that isn’t there, it gets pretty complicated at that point, right? So you can’t really talk about it that way, because it’s over, that way of understanding the world. That’s why I try to get people to actually see the Earth go up. The Earth rises at the night time, and falls in the morning. So if we could learn to say, I’ll see you at Earth rise, and we know that that’s seven o’clock at night, you could begin to get some sense. That’s what I loved about Santa Fe. You went outside and you knew you were on a rock just flying through the universe. It’s a whole different way of thinking about it.

We’re not about to get anything that is going to significantly change everything, in music. There’ll be big breakthroughs that the commercial people will do. If you look at what Apple has done, every new object they make makes it easier for you to buy things and harder for you to not get those fucking things thrown at you. I know there are ways to turn it off, but every time I want to play a sound, iTunes pops up. You have to fight the thing or live with it. It’s not conducive to the kinds of things we are talking about. The fine art world is less capable of producing that than the other world because it’s now become significantly a living museum. They don’t want to change. And the people there don’t want to change. And there’s no reason to because it’s not the only trajectory of music.

EISINGER: What about the moment where those worlds collide? Like when Silver Apples of the Moon climbed the charts? Do you see that as a moment in new music?

SUBOTNICK: Yes. And I’m happy that it was because that’s what I was looking for. I never dreamed that it would ever happen, I just dreamt it. Silver Apples was a different way to conceive music. It didn’t have a keyboard. It had pitches and all that stuff. But it was out there. It was a different way to put it together. Everything about it was different and there was nothing really like it. And because of this trajectory, and I—physically, mentally, by seeing the Earth go up, by getting rid of the clarinet, and getting rid of all that background, but keeping all my knowledge and ability to make a ground zero piece of music with electronics, thinking I was a hundred years in the future and what that might be like—I think I accomplished that. I got letters from people saying, “I wake up in the middle of the night seeing green monsters from another planet, is that what you had in mind?” [laughs]

I’m sure a lot of people were on dope and hallucinating and all sorts of things, and I didn’t have any of that. It wasn’t like I cared. It was my objective and I think I fulfilled it because I knew what the timing was. I knew it was a very short period of time before the industry would take over and that they would take me over like everybody else. Once Switched-On Bach came out, that then became the model that everybody used. They didn’t use my model. It wasn’t until much later, when the younger people from the pop world became the avant-garde people.

So there will be all kinds of new musics. But that’s not where music is going. That’s only where you know. And there’s kind of a dead end for each one. They don’t disappear. We continue symphonic music. We continue country Western. We continue disco. We continue all these things. They don’t just go away. And you think they would, but because of the recording, they can’t. If it was only on printed paper, it would disappear. But the literacy in music is through the ear, so a lot of people are experiencing it for the first time.

The real change I see in the future is a technological shift. Like automobiles. Once they become driverless, you don’t need parking lots, you don’t need parking places, it changes everything. In music, that kind of a change isn’t going to be because of the content of the music. It’s going to be the delivery of the music. You couldn’t do it now, but in the future, if the delivery gets to that point where we actually are translating music neurologically, down the line that will change the delivery of music, so that we actually get rid of musical instruments as such. So if I have a prediction, I don’t know about that in particular, but it’s going to be in the delivery not the content, and heading in that direction generally.

EISINGER: What do you think is the greatest lasting impact of Silver Apples of the Moon and why does it still resonate with people today?

SUBOTNICK: I think it resonates because it is pretty unique. I placed myself in a unique spot in that period of time. I had to step aside from the modernism that I grew up with and try to imagine a world where records were the way you heard music. And so you would have a listening room, and that was the new chamber music. It was chamber music where you had discs and you would pull them down and put them on your record player. So sort of a science fiction view of the future. And I had to write a piece for that. So it wasn’t going to sound like a Beethoven string quartet quartet or like Wagner or something like that. It wasn’t going to be modernist. It would be something else. And it couldn’t have the same kind of shape that you would do in a concert hall. It would be something different than that. And I did all those things, not everything perfectly, but I think when you do listen to it from this point on (I’ve been forced into now) there really just isn’t anything like it from that period. It wasn’t a period that this was going on!

I was trying to break the fine art tradition. I’m not against fine art. Not at all—that’s really my home. But it’s only a small percentage of the human being on the Earth.

I know it’s not a great piece, and I’m not sure it’s a particularly good piece. I mean, it’s good. But I don’t think it’s so good that it’s going to live forever for that reason. I think it’s going to stand exactly for what I made it, and that’s pretty damn good! That seems to be what has happened, and there’s a certain momentum that makes that more likely that that’s going to be there for some time.