Midnight in Berlin with Clare and the Reasons

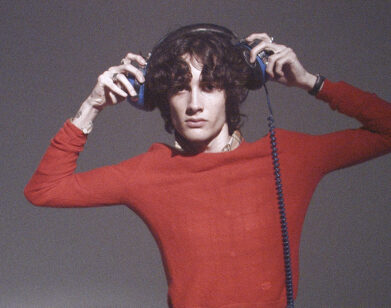

ABOVE: CLARE MULDAUR.

To write and record their third album, KR-51, Clare and the Reasons decamped from Brooklyn to Berlin for eight months. Their sojourn sounds very music-video picturesque—whizzing past the remains of the Berlin wall on scooters, eating homemade apple cake in a cute rural village. This “Midnight in Berlin” hazy lens is perfect for the band: Clare Muldaur’s breathy, vaudeville vocals, accompanied by Bob Hart’s guitar and her classically trained husband Olivier Machon’s strings. Berlin’s blotted past gives the band a mournful anchor to their music—songs such as “Colder” were written after sobering museum visits—allowing for a darker album.

Now back in the states, Clare recently spoke with us about Berlin, her early equestrian aspirations, and her Interview-loving grandmother.

EMMA BROWN: Hi, Clare. Where are you right now?

CLARE MANCHON: I am actually on Martha’s Vineyard. I’m visiting family. I have some dear friends from Berlin visiting, so we all got to come up from New York for a few days.

BROWN: Are these friends you made while you were recording your album in Berlin, or did you already know quite a few people before you moved there?

MANCHON: Two of them I knew before, through music, and one of them is a true, real German. [laughs] We’re having a great time. Good people go to Berlin. I don’t know what it is, but it seems to attract a really good kind of human being.

BROWN: What made you decide to record KR-51 in Berlin?

MANCHON: I wanted to learn how to be a good human being. [laughs] No, I think it’s just such an attractive city for the quality of life, the cost of living. The level of artistic integrity and output there is just incredible, and I think we just found it really fascinating historically and wanted to be a stranger in a strange land and be in a different headset to write music. Your surroundings really help to shape how you think about things.

BROWN: Did you read a lot of history while you were in Berlin?

MANCHON: I did. I’m no buff, but I tried to read about all the things that were around me—the general history of Germany. It’s been a rough one for the last 2,000 years. But Berlin is an incredibly hopeful place. They’ve come out of such darkness. I think they own what happened, in a way. Sometimes my mind went to the comparison of slavery in America, and how recent it is, how much we totally disconnect ourselves from it. The Germans, from what I can tell, are more like, “We did this. The German people did this, and this is what happened.” And in America, it seems a bit more like we’re not connected to it and there’s not a lot of healing around it.

BROWN: Has that changed how you feel about America’s past? Connecting yourself personally to the past is such a painful thing to do.

MANCHON: It is, it is! And it was so interesting; I was having a conversation with my German friend who’s from the south of Germany, and I said, “How do you reckon with this? How are you raised in this country to understand what happened?” And she said, “I walk around, every day, and I can’t even understand what to do with the guilt.” And when you’re a kid, they sort of pound into you, “You did this. We did this. Your parents did this. Your grandparents did this.” I think there’s just a very clear line in the sand of what happened and who wants to move forward knowing what happened. It was interesting to talk to my friend about that, because I thought it might be a sensitive subject. I guess it kind of was, but the answer was that she just lived with a lot of guilt in her pathology and her DNA.

BROWN: I saw the video for your song “Make Them Laugh” and heard it was based on a New York Times article, “A Young Clown Follows in his Father’s Giant Footsteps.” Do you often write song based on articles, or are they generally more personal?

MANCHON: Well, I did write a song about Pluto after waking up and reading what had happened. I thought I could personify Pluto a little bit. I wrote that song on the album called “Colder,” after seeing a Jewish photography show at a photo gallery in Berlin called the C/O Gallery. It was just all these extraordinary photos from just after the war taken by this Jewish photographer, Fritz [Eschen]. These photographs were really, really striking, just showing the level of dilapidation, but somehow the way the people were still getting dressed and looking very presentable on the street, and the women had done their hair and their shoes were shined, it was this very surreal, interesting example that life somehow does go on, and people do pull themselves together after such atrocities. That “Colder” song was specifically written about this one photograph of this sea of people in Charlottenburg just after the war, just before the Russian occupation. It was a protest—I’d never seen such dead-looking people, but somehow standing—and they just looked devastated in every way and burned the thing in my brain. So I wrote that, which is quite a dark number.

BROWN: The whole album seems more somber than your previous record; do you think that’s because of the setting of Berlin?

MANCHON: I think it must be. I think it’s probably a combination of my own interior world and that which was around me by being in Berlin. I think there’s a difference between dark and depressing. I do think it’s dark, but I don’t think it’s depressing. Personally, I’ve just sort of gotten a little bit darker. I’ve had some health issues, and just some stuff, and I think that’s what happens. As you go on living your life, you’re not only going to see the rosy side of things. I think it needed to be this way, and it needed to be in Berlin, maybe to help bring that out, so I was grateful to have that.

BROWN: What do you see as the point of your music?

MANCHON: Ooh. That is such an impossible question. [laughs] I was actually thinking the other day; we all want to have a purpose, everybody on Earth. I hope that my purpose can be, has been a little bit, and can continue to be giving people something that makes them feel something. I think that’s all any artist wants, although maybe other artists want a lot more than that. You want to make somebody stop in their tracks, and you want to make them get affected by what you’re doing, whether it’s happy or sad or totally in despair by some arrangement you’ve done that makes them go into a really pensive place. I hope that’s my purpose—to share what we’re making with others and have them feel something as a result. And if not, what are you gonna do?

BROWN: If I was having a conversation with someone and afterwards they said, “Oh, that just made me really upset, I’m in such despair now,” I’d feel really awful about it and try and reassure them. If somebody comes up to you and says “I loved your record, but it made me so sad, and I don’t know what to do with myself,” would you feel guilty?

MANCHON: No… no, no, no, because I know that the sadness is inside of them and I’m just helping to make them feel something. I think we can all go through our day and be completely shielded by what we feel. We can distract ourselves to a point of being totally numb, which is fine for a while, but I think it’s also good to stop and feel something about it. I really love it when people sometimes come up after a show and say, “You made me laugh and you made me cry,” because that’s equally important. It means a lot.

BROWN: Every interview I read with you sort of starts off asking you all these questions about your family and asking you if you felt like you were always going to go into music, and you always say that you wanted to be a horse rider or a professional equestrian. When did that change?

MANCHON: Well, I was a very serious horseback rider. I was actually admitting this to my German friends and they’re just coming around to believing me. I had like a sponsor, and I flew to Florida every weekend in the winters. It was very serious. The way the horse thing works is when you’re 18, you get out of the very prestigious world of being a junior in the equitation and hunters and jumpers, and you either have to choose that as a life path professionally—you become a professional—or you become an amateur, which you would only do if you were very wealthy. It seemed to run its course. I went to Berklee College of Music for this summer program when I was 17 and I was just completely blown away. I was like a zombie for music after that; I wanted to learn about it and then I wanted to take it really seriously. I also found that it was becoming more and more a way that I needed to express myself, as corny as that sounds.

BROWN: You must have had no free time as a child if you were playing all those instruments and horse riding.

MANCHON: Oh yeah. It was up at 5 a.m., go to the barn, clean out the horse stalls, feed the horses, take the bus from the barn, then go back to the barn or to a music class after school. It was super intense. I do not know how my mother did it. She’s just incredible. If we have children, I will never let them look at a horse, because I do not want them to get that bug. [laughs] It’s like a disease.

BROWN: Do you still horse ride?

MANCHON: I don’t. The kind of horse [riding] that I was involved with was such a snobby, high-end thing—it’s not the kind of thing you can have one foot in. You have to be totally in that world. And music, you have to give 100% of your attention to and 100% of your time to. I feel very lucky that I’m able to do that. No regrets, whatsoever.

BROWN: I was told that your grandmother is a New York society lady who loves Interview. Is that true?

MANCHON: [laughs] Yes. I’m actually at her house. I’m out on her little patio. She’s really, really fabulous. She’s 94, and she thinks that old people are really boring. She used to be at both Barneys and Bergdorf’s. She had a pillow company and sold exclusively for a while to ABC Carpet. She’s just totally enthralled with all things design and fashion. She’s incredible.

KR-51 COMES OUT TOMORROW, JULY 10. CLARE AND THE REASONS ARE PLAYING AT LE POISSON ROUGE WEDNESDAY, JULY 18.