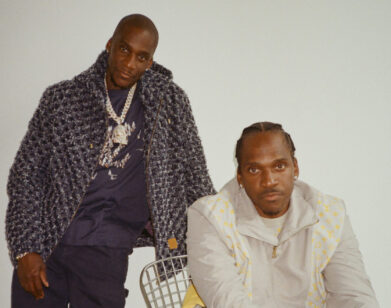

in conversation

North Face Jackets and Jordans: Aminé and Jak Knight On Growing Up Black in the Northwest

Aminé is doing some different shit. The rapper from Portland, Oregon has been creatively shimmy-ing his way through the musical landscape with a scrumptious and rebellious sound that not only excites his loyal fanbase, but also shakes the culture. Though the Aminé experience was founded on the idea of having fun—from catching a movie with “Caroline” to nonchalant pink and yellow wigs in rural areas, and even a conversation about Jesus’s hoes in his latest visual for “Compensating” featuring Young Thug—with Limbo, his long-awaited second album, Adam Aminé Daniel is exploring the gray area before real adulthood hits. Or, “Britney Spears when she was bald,” as he describes it on “Pressure in My Palms,” featuring Slowthai and Vince Staples. Even though having fun is still something he enjoys, Limbo is about what happens after the fun is over, or better yet, when the fun becomes a bore. A few days before Limbo dropped, Aminé linked up with his longtime friend, the writer and comedian Jak Knight, to discuss the trials and tribulations of growing up Black in the Pacific Northwest, the legacy of Kobe Bryant, and dating white girls. —ERNESTO MACIAS

———

JAK KNIGHT: Look, the nigga’s a rapper—the fact that he’s even on-time for this is pretty crazy.

ADAM AMINÉ DANIEL: Yo.

KNIGHT: Sup, how you feeling, bro?

AMINÉ: I feel cool. We just finished editing and compensating the video.

KNIGHT: How’d it look?

AMINÉ: It looks crazy. The skit in the beginning is wild.

KNIGHT: Dog, I was trying to explain it to my girl, and I just sounded so fucking stupid trying to explain it. I was just like, “You got to see it—the fucking room with the tennis rackets—these motherfuckers doing something different. This is dope as shit.”

AMINÉ: Bro, that’s one of the best scenes. There’s so many dumb ass takes of you dancing crazy. Bro, niggas had more than enough to fill a whole music video, it was great. When’s the first time we met? We met at what, the Satellite?

KNIGHT: We met at the Satellite, which unfortunately just closed. We met at Brandon Wardell‘s show.

AMINÉ: I just pulled up because he told me to come. I knew of you, but I didn’t really know you. I didn’t know you’re from Seattle. That’s what really shocked me. After you did your set, I was like, “Damn, this nigga’s funny as hell and also crazy.” Then he walks off the stage—I don’t know if you were single at the time, but you were definitely crazier back then, and it was funny as hell. You walked off with this crazy energy, and you were just like, “What up, nigga? I’m from Seattle.”

KNIGHT: Girlfriend or not, I’m still like that. It was so weird because my POV of it is, and I told you this time and time again—there was nobody from the Pacific Northwest to be a voice for this new generation of nigga, and I felt crazy going anywhere being myself because there was no pop culture reflection to refer to. If you were a wild Chicago nigga, there’s a 150 million wild Chicago niggas to reference. When I first saw you, I was like, “I need that nigga to become more famous so I can get more money. The more famous Adam becomes, the less I have to explain about myself.”

AMINÉ: That’s so fucking funny because it definitely was not easy though. Every time I said I was from Portland, niggas was like, “What?” They was definitely confused that a Black dude is from the Northwest. I don’t care if it’s in front of a million people or at the Satellite, just seeing you killing it on stage was dope because I didn’t feel alone as a Northwest nigga in Los Angeles. In L.A., you’re not supposed to be proud of being from the Northwest, but I am.

KNIGHT: It was such a good feeling to know that someone else wore a North Face jacket and Jordans.

AMINÉ: Nonstop.

KNIGHT: North Face jacket, and then you dated girls who wear Tom’s. You just out here rocking it—there’s such specific things about our niggadry.

AMINÉ: I like niggadry. That’s a good word.

KNIGHT: I’m so excited about all the representation that’s on TV today for being Black. Before, we had representation being Black on TV, but we didn’t have the specific representation of being Black on TV. I think that’s why Netflix just literally bought 10 years and 5,000 episodes of shit we all grew up on. I know that there’s niggas in Iowa. I know that there’s niggas in Tacoma, Washington who hear me tell jokes, and they’re like, “Yep. I know that bitch.” I think what we’re doing, and the fact that we came together so quickly is because we’re like, “I know that nigga.” In my core, I know this nigga because I had a sleepover with him in sixth grade. We used to go get fucking Mambas from the 7-Eleven and another nigga would steal some shit.

AMINÉ: I forgot about Mambas. Oh my god.

KNIGHT: Or you would do the slick shit, and the nigga would get too many Slurpees, and you would just steal a bunch of Hot Cheetos.

AMINÉ: Jesus Christ, that’s funny as hell. I definitely think I never noticed it growing up, but if you’re a Black dude from the Northwest, that shit is unique as hell. There’s definitely a fit that’s regular, there’s definitely the habits you have that are regular. It’s definitely unique in its own way.

KNIGHT: Well, you have to hold on to whatever blackness you have, and you can’t let nobody shake that shit. Because there is nobody else reaffirming it other than your momma and your daddy at the house. Every day you leave your door in Oregon and Washington, or in any space that’s predominantly white or anything that isn’t you, and you have to go out there and take your blackness, and you have to hold it, and ball it up in your fists. If anyone tries to undo your fists, you got to be like, “Nah, nigga, this is the truth. This is the answer to all the shit.” You have to wait 18 years to go to L.A. just to unball your fists. When I was in London, I balled up my Seattle niggas, and opened my hand a little bit, and Brixton niggas were like, “Yep, I know that.”

AMINÉ: You really got to walk out. Your blackness is literally something you have to hold on to really tight when you live in Oregon or Washington. I remember every Black history month, or every time “negro” was loosely used in school growing up, that was a terrible experience. I remember this white boy next to me asking, “Why do we celebrate Martin Luther King day?” And I was like, “Damn.” I had my fists balled up, that same feeling that you’re talking about. I had to really explain it, which was just annoying. That feeling is real, I can’t even lie. I know there’s tons of niggas that identify with that.

KNIGHT: You know what? They shouldn’t even have to.

AMINÉ: Exactly.

KNIGHT: They should be able to be where ever the fuck they at and have enough resources, and Jak Knight comedy, and a fucking Limbo album. Because some niggas just don’t want to leave. I do love Seattle. When it’s all said and done, I’m gonna move back to the Pacific Northwest because I’m a Pacific Northwest nigga. So many people run away from that. I’m Black for sure, but on my tombstone, I’m a Seattle nigga. Period.

AMINÉ: I definitely don’t think I identify with an L.A. nigga more than I do with a Portland nigga. That experience is different. I want to move back too, but I wish it could be better for us. Growing up in Portland, I always wished there was a yearly event, or something, that felt identifiable to us. There was a festival in Washington, but it always felt like—

KNIGHT: The bikes?

AMINÉ: Some hipster white shit that I couldn’t really identify with. I never felt like I was welcome there. There’s been tons of years in my life growing up in the Northwest where I wish there was something I could go to, or something I could be a part of and feel welcome at. So, that feeling is very real. I’m sure tons of niggas have tried, but they never succeeded. You need money, you need a connection. They just don’t give a fuck about a Black nigga throwing a festival, or a Black nigga throwing a party. The city will close it down. There have been tons of set-up ways for niggas not to be successful in that city, or Seattle, I’m sure.

KNIGHT: You know how awesome it would be to be eating an elephant ear while Project Pat raps?

AMINÉ: Bro, it’s so funny that you say elephant ear.

KNIGHT: I just want to have a big-ass elephant ear in one hand, and a caramel apple in my other, and to have Three 6 Mafia scream at me.

AMINÉ: Are elephant ears normal anywhere outside the Northwest?

KNIGHT: I haven’t had it anywhere else. I be going to Red Robin asking for elephant ears, I be at Nobu being like, “Yo, this sushi shit cool, but y’all got elephant ears?”

AMINÉ: Just hearing you say elephant ear really brought me back hella nostalgia just now.

KNIGHT: I think this is a thing that connected to the album. Do you know that you’re speaking on what a quarter-life crisis is? The transition of being a young man to a man in his late 20s—really prioritizing what and who you are? I think anybody can relate to it. The transition of being a wild young nigga, who thinks the best things in life are just being a wild young nigga, to death, and love. I can barely even listen to “Injury Reserve” without getting a little teary-eyed. I’m literally going through the same shit of transitioning from crazy early 20s Jak to, “All right nigga, I got a girl, I be paying insurance.” You just tapped into what that felt like, sonically.

AMINÉ: I think that question you just asked me was literally a question that a therapist would ask me, which is really good. You’re helping me recognize that in the album. I personally didn’t really know that when I was making it. I was just going through it, realizing my life was changing, and that these were the subjects. I don’t know how it is for a lot of other artists, but albums for me are examples of where I’m at in my life currently. I’ve never seen a therapist, so I’m sure a therapist could completely identify and help me get that. We didn’t come to the studio being like, “Yo, we want to make this sound like a quarter-life crisis.” The production just kind of happened the way it did, and the words just kind of happened the way they did as well. I guess I’m just figuring it out.

KNIGHT: “Woodlawn” felt like it’s that hit, but it still felt like yours. I’m so glad it’s at the beginning of the album because it felt like your reach back to your adolescence. Your reach back to me and my niggas driving around the city, being drunk, doing whatever the fuck we want to do. The rest of the album feels like you had an Earl Gray tea, and you had a poncho over your shoulders, and you sat at the chair, and then you wrote something, then your dog came and sat at your feet. It felt very, “Damn this nigga think he Big Little Lies? What’s going on?”

AMINÉ: I mean, true though. I definitely wrote this in a way where I was at peace. I’m always thinking about the future. “What is five, 10 years from now going to look like? Am I here to stay, or am I here to go?” That’s the crisis in your head as an artist, especially today. Music comes and goes. I don’t care how many platinum records or whatever the fuck you get. This shit can easily be gone next year unless you keep working at it.

KNIGHT: I do not think a comedian should be famous until they’re 33. So much of comedy or writing is you have to be able to explain life with life experiences. But music is built off of emotion, and the multi-emotional motherfuckers are young niggas. I think the way you took your young emotion into the transition—you can feel your feet are steady. Your hand isn’t trembling. You completely understand. Were there any moments on the album where you’re just like, “Damn nigga. Everybody can suck my dick.”

AMINÉ: Tons, bro. For me, it’s definitely the end of “Pressure Off My Palms.” It felt natural. I felt proud of what we’d done. “Woodlawn” and “Burden,” those first two tracks being the first two, it’s for that reason specifically. I’m really proud of the way we were able to put those songs together just because they both accomplish the two feelings I was trying to give on the album, whether it’s dope hip-hop samples and somber vocals, or whether you just want to turn up with your niggas. I never want to take myself too seriously.

KNIGHT: You take intros pretty fucking seriously.

AMINÉ: Intros are so fucking important to me. I literally want to pick up my phone and break it if I hear somebody’s album and it’s them talking for 20 seconds and that’s it. The intro is the opportunity to really show what the album’s about, and really update people on your life. I treat intros like they’re updates, or the tone of where I’m at in my life, whether it’s self-explanatory, or whether it’s figuratively. The sounds really matter to me in an intro because it’s your first impression. “Harbor” was before the words. It was just the beat.

KNIGHT: The kid who made that beat is European, right?

AMINÉ: His name’s Matt Weather. He’s a 19-year-old white boy from London, which is crazy. I had a session with DJ Premiere, right before COVID.

KNIGHT: Crazy.

AMINÉ: Flex. I played him “Shimmy,” and the first thing he said was, “Damn, Charlie Baltimore would’ve been proud.” To hear Premiere say that was fucking crazy. I was trembling in my seat. Then I played him “Burden,” and I told him a white boy made it, he was like, “Get the fuck out of here.” I’m proud of Matt because he really played me that beat like it was just regular. He was like, “Oh, yeah. That’s just a beat I was working on.” He didn’t think it was that crazy, and I was like, “No, nigga. This is insane.”

KNIGHT: You go absolutely apeshit on that motherfucker.

AMINÉ: It was fun putting that together.

KNIGHT: Man, that “Kobe” shit hit. People coming up to me like it’s the end of Titanic. People be damn near teary-eyed talking to me about this shit. What went into that?

AMINÉ: I think as soon as you hear it, you know what it meant. It wasn’t even the words, it was the emotion in it, the stutters in the words. Trying to piece those words together literally sounded like a grown man trying to piece his emotions together. This wasn’t one-directional, just for people who used to hoop or some shit. It was about death, and how it really affects your maturity.

KNIGHT: Kobe is such a microcosm of this whole shit fuck of a year. When I heard it, it just sounded like this big forceful ego death that every nigga had to kind of be like, “Oh, shit. God is dead. I didn’t know they could kill that nigga. That means I’m easy.” Do you feel a type of way about a project you care so much about coming out in such a fuck of a time?

AMINÉ: I mean, it’s not what I wanted, of course. But making these songs were some of the best times of my life. They really helped. It’s so therapeutic for me, just to even release it. I never planned for it to be out now—it was supposed to be out in spring—but things change, and life is life, and you just roll with the punches. I really wanted this project to be out there for people because I knew they could cherish it, especially during times like these when they’re at home.

KNIGHT: They need it.

AMINÉ: I feel like I love turnt-up shit, and I need turnt-up shit every month, and every hour. But I also need the balance of shit that’s introspective, and shit that makes me feel like I could relate to it as well.

KNIGHT: You said you haven’t been to a therapist. I’ll check your Instagram, see your story, and one story will be like, “Yo, come get this long sleeve Limbo shirt.” The next one will be like, “They’re shooting moms in Portland.” I’m sure that’s not good for your mental health.

AMINÉ: I honestly would rather not be putting out an album at all for a couple of years, but I also know that’s not up to me. It’s for the fans, too. It’s something that they’ve been waiting for two years, and I know they need that more than ever right now when they’re alone at home figuring shit out, when there are people losing their jobs. I know that music for me was always therapeutic. It gave me something to look forward to. I guess that’s the real point of it.

KNIGHT: We’ve talked a lot about that “Momma” to “Becky” decision—why you didn’t put “Becky” before “Momma”?

AMINÉ: The conversation around those two tracks next to each other was because I thought it was so funny that I had that first lyric, “Momma said don’t ever bring a white girl to me.” I’m not going to name names, but I was in a session with a producer and this other producer, and a white girl was there and she heard that. She was like, “Your mothers would actually tell you to not date a white girl?” And I was like, “Yeah.” That was so funny to me because it really told me that the conversation has never been put in music. I haven’t heard that lyric in songs. I knew it was something that people needed to hear. It wasn’t even about interracial dating so much as it is about what it’s like growing up as a nigga in Portland, Oregon. That’s what the song’s tone is more about—the second verse talking about white people clenching their purses when you walk around is really the feeling growing up in Portland. I was in middle school walking around with my white homies feeling really kind of confused as to why everyone looked at me like I didn’t belong. It just felt weird.

KNIGHT: You also had an $80,000 watch on, so I think that was probably the big issue that everyone had.

AMINÉ: You’re stupid as hell. I’m saying this happened before the music shit, even walking around in middle school. It wasn’t pleasant, man. I definitely hated myself at times and hated being Black in Oregon because it never felt like we belonged. It felt like no one wanted us there, and that hurt. That really hurt growing up.

KNIGHT: You know, you’re kind of throwing up all of these pieces of your life, and you’re telling us that you’re setting up for the next chapter, or the next era of you being a man. You got any ideas of what that is?

AMINÉ: That’s a really good question. I honestly don’t know. I’m not going to sit here and make up some great statements. I think that’s the point of Limbo. Niggas is literally in limbo. I’m still figuring it out, man. I don’t have any idea of what being an adult looks like, whether it’s a child, whether it’s fucking—I don’t know! All I know is as I get older, I am appreciating family and friends and experiences so much more. I was taking my love for my family, experiences that I was having, and success for granted. I was definitely enjoying it and living in the moment, which is also good, but to sit back and call your mom randomly on a Sunday and talk for five hours about her life growing up is almost better to me than a new Rolex. Do you feel like growing up is changing you now?

KNIGHT: I feel like our age group got the short end of the stick of the economy collapsing, Trump, I could go on and on. We’re kind of being beholden to it, but also underneath us is this atomic bomb of, “Y’all ain’t going to do us like you did them niggas.” I look at them young niggas like, “Correct. That is right. Fuck all those niggas, bro. Fly. I agree with what y’all doing.” It’s like Michael Jordan with Space Jam: just because you climb to the mountaintop and win three championships doesn’t mean there are another three championships on another mountain. You eventually have to climb back down, figure out who you are, and figure out what the next steps are going to be for yourself. More music needs to address the pivot rather than the constant euphoria of whatever moment you’re in.

———

Styled by Aly Cooper.