apple of our eye

A. G. Cook Dissolves Into the Light

A. G. Cook is the most ambitious producer in the world. Seven years after founding his PC Music label in London, he’s just released 2 debut albums: Apple, which has 10 tracks, and 7G, which has 49 tracks over seven discs arranged around his seven favorite instruments. This year, he’s also produced Charli XCX’s album how i’m feeling now and Jónsi’s Shiver (out October 2), released an EP as DJ Lifeline, and put out the 31-track mixtape Appleville, featuring friends and many artists that may or not be him. Taken together, it’s the most interesting artistic project of this plagued year, a pure expression of art for art’s sake, a deep personal archive, and a deranged prog masterpiece for a summer of total delirium. It’s a labyrinth to be explored here in our bardo where time stands still, an absurdist cubist puzzle that shows Cook and his collaborators from several angles at once, and, like all the best pop, makes you feel all kinds of distinct, conflicting emotions at the same time.

Talking to Interview from his hideout in Montana, he explains how to transcend streaming, explode palettes, and listen aggressively, while examining the duality of pop, software as prosthetic, production as self-portraiture, the dissolution of binaries, and the infinite possibility of music.

———

DEAN KISSICK: You finished Apple around a year ago. Why did you decide to release it now?

A. G. COOK: I had always wanted to have quite a long lead-in time. I was very used to there being loads of PC Music releases that were the opposite of that: we have it in, we upload it to SoundCloud. Sometimes we have a bit longer, but it’s never really been executed to the standard I wanted to go for with an album, especially with trying to transcend the streaming vibe. I wanted to have enough lined up and figured out that I could make it a way more interesting rollout than just getting it ready when we need it.

The 7G release was planned around the time that I was wrapping up the album, but it turned into a much more confident form as we got closer. I was thinking of maybe doing seven mixes, breaking up the palette that I had on Apple. Somehow, when I listened back to those album mixes, I was even slightly shocked by how specific the palette was in terms of instruments, or the way I was using all those things quite equally, whether it’s Supersaw or guitar or what I would call “extreme vocals.” I wanted to do something that would flesh it out, explain it and give it a perspective that was not just, “Oh it’s a novelty, I’m playing guitar now.” I was always thinking of exploding the palette of the album, and this year, as I got closer to it, I thought, “Oh, mixes don’t make as much sense now.” It should just be another debut album or a partner album to Apple.

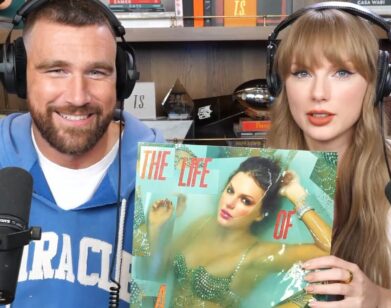

A.G. with Charlie XCX. Photograph by Charlotte Patmore.

KISSICK: Let’s talk more about exploding. You have a very exploded approach: you make multiple versions of the same song, and sometimes the same riff appears on different songs. You have many different aliases and two debut albums, but one of them’s got seven discs.

COOK: I mean, there’s a few layers. I guess when I say the word “exploded”, I’m always thinking of those instruction manual diagrams where you suddenly have an exploded view of something as well, and it’s a multi-perspective way of looking at something. Whenever you listen to music, there are so many expectations of what normally happens: a chorus, or bridge, or even just how you expect someone to sound singing. There are all these things that you don’t necessarily have to think of in a very active way, but all these expectations playing off other music, like all the other music you’ve ever heard up to that point. A song can feel interesting because of everything you know about all that material up to that point. You have a lot of songs where the outro, the bridge will suddenly have this total shift, but that wouldn’t be satisfying at the beginning of the song. You’re building that fun narrative and giving it a completely different perspective.

Doing covers, I was really interested in that gray area. Because it’s not a remix, and you can just completely do it as long as you don’t edit anything, as long as the lyrics are intact, you just waive the publishing over. That’s one of the reasons I became interested in covers as well as remixes of my own material. I think I might be particularly aggressive as a listener. I’d hear a song like “The Best Day” by Taylor Swift—I just heard it in a supermarket—and I thought, “Wow, the melody of this is really skillful and oddly dissonant.” I thought, if it was slowed down by a good 50%, you’d really hear how intense that vocal line is. And then once I had that idea, I also wanted to investigate the song itself, to try out my own version.

A.G. singing ‘Chandelier’ at Pop 2 live show in New York City in 2018. A.G. Cook/PC Music.

The “Chandelier” cover also came from hearing Sia’s original track and thinking, this is such a ridiculous song, so audacious. It’s really skillfully evoking this pop music metaphor, swinging on a chandelier like a soaring vocal. I wondered, what could possibly make this soaring vocal more soaring? Well, if the key dropped at the same time as the chorus, you would technically be able to have even more space above the ground, swinging on the chandelier. And if you could trust someone like me trying to sing with someone like Caroline [Polachek], that’s going to create even more distance. So in a way, it’s an aberration of “Chandelier,” but it’s also getting closer to the true version of “Chandelier,” or my own truth regarding that song. This exploded view of things, for me, feels like a really genuine way of looking at things. I think the true version is in between the two albums, between 7G and Apple, if someone manages to absorb both. The true debut is in the crosshairs.

KISSICK: Damn.

COOK: I feel like, for people who have managed to immerse themselves in it, that’s communicated in some way. Also, not to go on about lockdown, but—

KISSICK: No, please do.

COOK: It gave me more confidence to do something that would probably require more listening, because I was just fine myself doing that more. It’s way easier to get into more longform stuff now. Everyone has either more time, or different uses of time. I used to hear all these pop songs in Uber rides or in cafes, that’s how I sometimes used to know that songs did really well, because they’re around, I didn’t even have to choose to listen to them. Now that’s evaporated, I’ve found myself listening to full albums, or just other odd releases or mixes or things I was interested in but never got around to, and that also gave me confidence to make something that would require more immersion.

That’s enabled a more confident view of putting out a lot of content and hoping there are links. Even though I’m stepping out a bit as an artist, I don’t really feel like I’ve crossed the line between being a producer or a performer now. All those things are very connected to me. My work with Charli is quite personal. Obviously this is going inwards, using my own voice and having to figure out the right musical landscape. Multiple versions, or the demo quality of something somebody transformed into a slick version, is something I’ve always been interested in—that feeling of being self-recorded, and sometimes reworked obsessively, and sometimes left alone. I’ve always tried to encourage singers I work with to record themselves. I’m trying to make people aware that anyone can record themselves and anyone can be involved in that way and we can all do covers of any songs we want and generally remix things. That feels like a very real way of listening to and participating in music now.

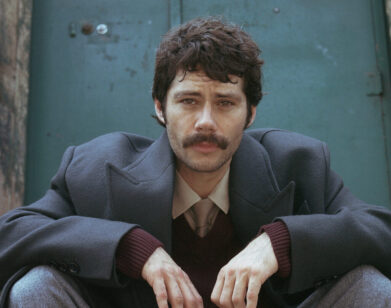

AG. Cook, SOPHIE and Charlie XCX. Photograph by Henry Redcliffe/PC Music

AG. Cook, SOPHIE and Charlie XCX. Photograph by Henry Redcliffe/PC Music

KISSICK: Do you think you’ll ever go full pop star?

COOK: That’s a kind of funny question, but I like it because I don’t know what it means. Just the definition of what a pop star is is changing so much. The pop star role is probably going to become more multi-layered and involved: people doing their own production, their own things, working with other people. I always stand at the same place and don’t move for a while. I don’t think I’d really go for becoming a pop star, and I definitely enjoy being in the studio, but I like that boundary being blurred. Over the last few years, I’ve just seen it get closer and closer to what me and my friends have done.

KISSICK: I read a quote from you, “Pop music is about confidence and escapism and how bittersweet those things feel.” Why are they bittersweet?

COOK: Let’s take a three-minute pop song, or something that’s trying to be like that. It tends to have quite a defined voice. This tightness, and the vocals being up front, and the lyrics being one central idea repeated, it can be really enjoyable to listen to something like that, and fun, but also bittersweet, because it’s monolithic in a way. It’s just escapism. I find my work, and listening to music, is a big form of escapism, because you get lost in this piece of art that has this very defined approach, even if there’s lots of interpretation and lots of personal resonance. It’s so well-defined for that duration of time, and that in itself is bittersweet because of the comparison with either real existence or real thought. There’s a feeling sometimes when you’ve worn a song out, or think it has a different meaning, or it becomes associated with a memory. It’ll function as dynamic escapism, but eventually you’ll associate it with that exact time and place that you got into it. The funny way that it interacts with your brain—that is how it’s bittersweet. I’ve always been drawn to music that has a bit of that. Not music that’s self-aware about that, but that encourages it by having some duality. Whenever I hear a song that’s just purely upbeat, or like one-note, it doesn’t really stick for me as much. I feel like “Oh Yeah” is a fairly good example, but there are a lot of songs like that.

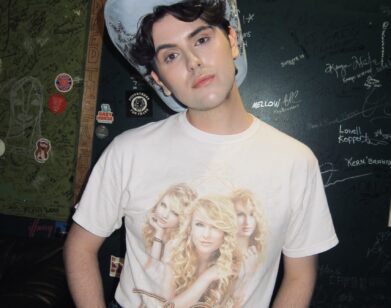

Photo by Timothy Luke.

KISSICK: You’ve also described Apple as your approach to personal computer music. Your approach to personal computer music feels very personal. Has this always been the case with you?

COOK: For me, what always made something feel appropriate to be part of PC Music was this idea of it feeling personal to the artist, but beyond that, someone’s using technology in a way that’s highlighting how there’s this interface between using a device and trying to be expressive with it. I’ve always thought of my own relation to music software as like having a prosthetic, because I can write music unplugged or at an instrument, but all my favorite stuff is done around the computer. I’ll be clicking things in, able to rearrange what I’m doing while I’m there. My brain is just operating on a different level. It feels like part of me, but it’s clearly this other element, the way the computer has become this musical notepad, the way I can even hear myself back immediately, layer things, edit things, click things in; the music I have done on computer feels generally more personal and more like myself and more reflective than I would have been. It’s this sort of capturing yourself, viewing yourself, and reflecting on it—consciously editing, but also losing yourself in the moves, ambiently existing in your own music. Some people ask, and this is a classic twentieth-century thing, is the computer going to ruin music? But I’ve always felt, for the generation that I’m part of, that it has a suggestive quality that is magnifying the humanity that’s involved.

KISSICK: That’s very hopeful. I’m also very hopeful. Do you think sincerity and optimism are particularly important now?

COOK: Sort of. As much as they always are. I think sincerity is a quality that sometimes just disappears when you start talking or thinking about it. I can see sincerity in all sorts of things: in a sarcastic comment, an ironic comment. It’s very much about context and understanding where other people are coming from. For me, it’s never been an issue. We’ve all been exposed to so much content and so much stuff, and some people like to think of a high and low culture, or certain things being guilty pleasures, like if anyone’s using pop music in a different way, then that obviously can’t be a sincere thing because it’s too conceptual. But actually, it’s probably like shocking sincerity, and that’s the bridge.

For me, the goal is more of a sense of freedom. If there’s any loose philosophical or political feeling in my stuff, it’s related to the sense that literally anything could happen. There are so few rules in terms of how I can put something together. It has to be sounds and it’s linear. That means you’ve got this crazy freedom at any moment to do something that’s expressive in a completely different way. I’ve enjoyed being prolific and working quite quickly and not getting too stuck in things, and not getting too stuck in concepts either. That’s what drives me. I’ve been talking lately about dissolving some of the binaries, like man versus machine. Electronic, acoustic. That’s the zone I’ve always thought about, but I’m starting to approach a level of experience with music where I can quite confidently talk about it. The binaries are just ridiculous. They’re very free-flowing and much more open than they tend to be defined as. That’s the niche I’ve been experimenting in and researching, and that’s the thing that makes me feel more optimistic.

Photo by Timothy Luke.

KISSICK: Can we talk more about the niche? The dissolving boundaries?

COOK: There’s this zone I’ve always felt annoyed by, not by the music itself, but by how people categorize it: the tasteful middle ground. “Isn’t that amazing how Radiohead mix obscure electronic music production, but with a more Britpop sensibility?” The way that tasteful middle ground was given more importance than the stuff that blatantly influenced it—that felt like duplicity. That whole time leading up to PC Music, everywhere I looked, I just saw people fighting for these opposites or different spaces. For me it was banal to even categorize things like that. There is a difference, you know, between OK Computer and “…Baby One More Time,” but there’s also a lot of overlap in how things are engineered and put together. There’s tons of craft going into Max Martin productions and there’s also tons of crazy gimmickry going into Radiohead and other things. It became a farce, listening to people argue over genres and authenticity and all that. I generally did, and still do, see a lot of things interacting with the same kinds of platforms. Even more so now that all music is done through computers. You could be trying to do the most acoustic, really nicely made country music, and you’ll see all these accidental parallels with other genres because people use the same tools and work in this hybrid environment. That’s why I like examples that actually go for it. It’s why I’ve been talking about Shania Twain. She made one of the biggest pop crossover albums of all time [Come On Over (1997)], and she feels very real, but it’s so slickly produced. It’s just so tight that the good tracks are perfect and the ones that don’t work are hard to listen to. A lot of records like that in the last couple of decades also had to do with the technological aspect. That’s broken a genre division without people even realizing it. It’s accidentally really progressive even though it’s totally within pop music. I think you’ll see way more of that now, with TikTok and so on. TikTok really flattened genres because it’s so condensed, so much about how you can pluck out a cut of something. It can be anything that ticks some sort of mystic box. I feel happy to be in this.

Although a lot of the core ideas are things I’ve been thinking about for seven or eight years now, they’ve opened themselves up to me in a way bigger way lately. Like having the confidence to apply myself to something like Jónsi’s album. I know that he’s a fan of the same music as me, and I know I’ve been influenced by his harmonic stuff, and now I can really try and navigate a way where it’s genuinely his voice, but also really ambitious. To do something like that, you have to be breaking down those boundaries that I was talking about. You can’t get hung up like, “Okay, now I’m going to make a piece of music post-rock.” Like, no, that’s not even useful to think about. Think about the real personalities involved and about material and try and make an open-minded, idealistic version of it. If you work enough on it, it’ll just come together.