After an 8-year hiatus, Robyn learns to move her body again

Robyn’s voice, like all iconic things, is complicated. It is at once sweet and clear, like that of a child star on the Broadway stage, but with the haunting, helium-alien quality of Björk’s trademark feather-wail. Robyn is a true eccentric and a total Tinker Bell and an emotionally adept healer of universal wounds. I knew it when I played her first cassette single in my bedroom and demanded that the world show me love—and what it’s all about. I knew it even more when, on a trip to Sweden during the fall of my junior year of college, I was browsing a record store and saw the sweet face of the former bubblegum star staring up at me defiantly. Ready for her “Konichiwa Bitches” revamp, she was now dressed like the leader of an interstellar biker gang. In the years since, she has proved herself to be part conceptual performance artist, part dance floor diva, even singing with the Lonely Island to jokingly remind us all to “pose nude for a family friend” and “never speak of it again.” When I danced to Robyn’s “Dancing on My Own” in the third episode of my TV show, Girls, I felt like I was posing nude. I felt wildly vulnerable, all limbs and breath and instinct. And I wanted to do her proud because her music had offered me so much joy and freedom at times when both felt hard to come by. Robyn’s new album, Honey (which I was lucky enough to tease in the final season of Girls), is both stripped down and amped up as she lets us in on the eight years of growth via pain that precipitated it. She is so deeply open and she gives us so much that it feels greedy to ask for more information, but I do anyway.

———

LENA DUNHAM: I’ve loved your work since I was a teenager, and you’ve gone off in so many startling, different directions with your albums that I sometimes couldn’t believe that I was listening to the same person. What have those transitions been like for you?

ROBYN: For me, it’s really defined by that feeling of not really knowing if you’re going to make it through or not. That’s usually when you transform the most—and it feels like a big risk because you really don’t have that safe space to go back to.

DUNHAM: You know, there’s a lot of talk about the fact that you’ve taken time between records, which it seems like almost nobody does anymore. Did you have self-consciousness about taking that time? And how do you feel about it now?

ROBYN: I think it was scarier when there wasn’t an album. But now that there’s an album, and there’s still all this love from the fans who have waited for the record, I just feel really happy to be able to release it. But what’s interesting to me is how the minute you start talking about it, it becomes more of a story than the actual experience of my own life. I love telling stories, but I also am more aware now of how complex reality is and how difficult it is to really explain what happened or how I felt. Maybe that sometimes makes me a little bit vague, because I don’t want to really put my finger on anything or set it in stone. In the beginning, it was because I was just really sad and heartbroken and I made these really important discoveries in my therapy that were so groundbreaking. It was hard for me to get out of bed and stuff. But after a while it became more about really enjoying how much there was to feel and think about and understand about myself. And when I got past the scary part of it, it became about climbing down so that I could hear all of those emotions more. The music I made also became really softer because of that.

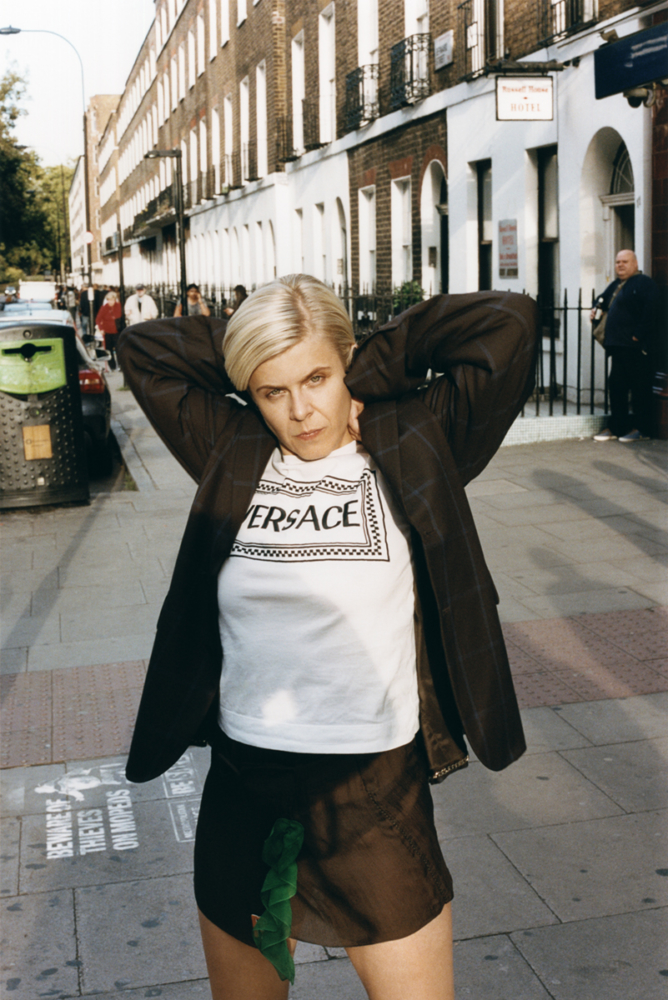

Jacket by Martine Rose, T-Shirt by VERSACE, Skirt by Prada

DUNHAM: How did you know when you were ready to put music into the world again? One of the reasons that I put things out so often is because I feel like if I stop, I might suddenly go, “Oh my god, I can’t believe I’ve been this vulnerable. What the fuck is going on?”

ROBYN: I don’t know much about making films or TV programs, but what’s cool about being in the studio is that you have more time. Filming costs so much money, so it’s such a nerve-racking process, whereas being in a studio is quite cheap compared to that, so you have more time to work on things until you feel good about them. That makes it easier to explain a certain feeling and be in a vulnerable place, while making sure it does what you want it to do.

DUNHAM: When I write, I feel like I’m in a process, and that’s a beautiful thing to feel.

ROBYN: Yes.

DUNHAM: You have such a pronounced aesthetic that has been such an unbelievable influence on pop. Does that aesthetic arrive and change naturally for you?

ROBYN:It’s really a process of going deeper and deeper into the things I like. So the aesthetic never really changes, it just becomes clearer and more pronounced. Hearing is a subjective experience, but I never really understood that it’s the same with seeing as well. I always thought that everything we see is the same for everyone. But having these more psychedelic experiences of being really, really sad made me realize how brittle reality can be.

DUNHAM: You’ve covered enormous ground emotionally. I remember reading when I was really young about the first song you had written being about your parents’ divorce. I know that your second album wasn’t able to have the same kind of release in the U.S. because you talked openly about the conflict of abortion. You’ve talked about heartbreak and loss. And now you’re talking about a huge range of emotions, and the experience of clinical depression and really intense darkness. For me, I know I can always get through any circumstance as long as I have art and a sense of positivity. But when I’m not able to is when the depression becomes something that’s almost outside of me, like a force that has whirled around my life and covered up everything.

ROBYN: I understand what you mean.

DUNHAM: I thought you would.

ROBYN: I don’t think that I had experienced that kind of depression before. It was a new level for me, and I’m actually really happy about it now because it made my life richer and allowed me to understand other people’s feelings better. For me, it was triggered by other things that happened outside of me—a breakup and a friend I really loved who passed away. It put me in a state I wasn’t able to control at all, where there was this disgust for everything and nothing really mattered.

DUNHAM: I’ve had that moment in my life a few times, and I think the moment where you see yourself making art again and your inspiration comes back is better than anything else. When you want to ride your bike again. When you want to go to dinner again. When you want to hug your parents again. Was there a first song or lyric when you thought, “Oh my god, I’m back”?

ROBYN:It was parts of “Honey,” that line, “The waves come in and they’re golden, but down in the deep, the honey is sweeter.” There was such a physical pleasure and sexuality to making music and creating this soundscape in which my body could experience those kinds of feelings again. That’s when I felt like I was coming back—but it wasn’t even about coming back, because I myself had really changed.

Jacket by Martine Rose, Skirt by Prada, Shoes by Paco Rabanne

DUNHAM:Your dancing has been such an influence on me. Did you miss dancing during this period of privacy? Or was dancing something that you did in private?

ROBYN: A lot, actually. When I started to move my body again, dancing was the first thing I did. I learned how to dance samba with my friend from school who’s a samba teacher. She’s amazing! She works in a hospital with really sick people who are dying, and when she feels like she needs to regroup herself, she goes on vacation to Berlin and goes raving, or she goes to Brazil to dance samba.

DUNHAM: Wow, that’s amazing! Part of the reason your music speaks to me so much is that even when you write about romance, you’re using it as a metaphor for something that’s bigger and universal. “Dancing on My Own” is all about these bigger questions of what it feels like to be a person and try to get pleasure from things in the world. It’s not really about looking at somebody else from across the room and wanting to know if they have feelings for you or not. So much of this album comes from heartbreak, but it also brings you to these gigantic questions.

ROBYN: I think writing about romance is about defining what’s in between people—because there’s something really bad about discovering that you actually don’t know what anybody else is feeling. You can guess and have ideas, but then there’s always going to be that distance between you and someone else. I was never really friends with that idea until just recently. Of course, some people are much more okay with it. But I think connection is the thing that is the most real. That’s why I love listening to Prince or Kate Bush, because it makes me feel like, “Oh my god, I know exactly what that feels like!” Sometimes I think that maybe that’s what romance is about—it’s a way to mirror yourself.

This article appears in November 2018 issue of Interview Magazine.

———

Hair: Kei Terada using R+Co Hair Care at Julian Watson Agency.

Makeup: Thom Walker using Bobbi Brown Cosmetics.

Production: LG Studio.

Photography Assistant: Paul Lehr.

Fashion Assistant: Camille Marchand.

Manicure: Jenni Draper at Premier Hair and Make-up.

Special Thanks: Kimpton Fitzroy London.