LIT

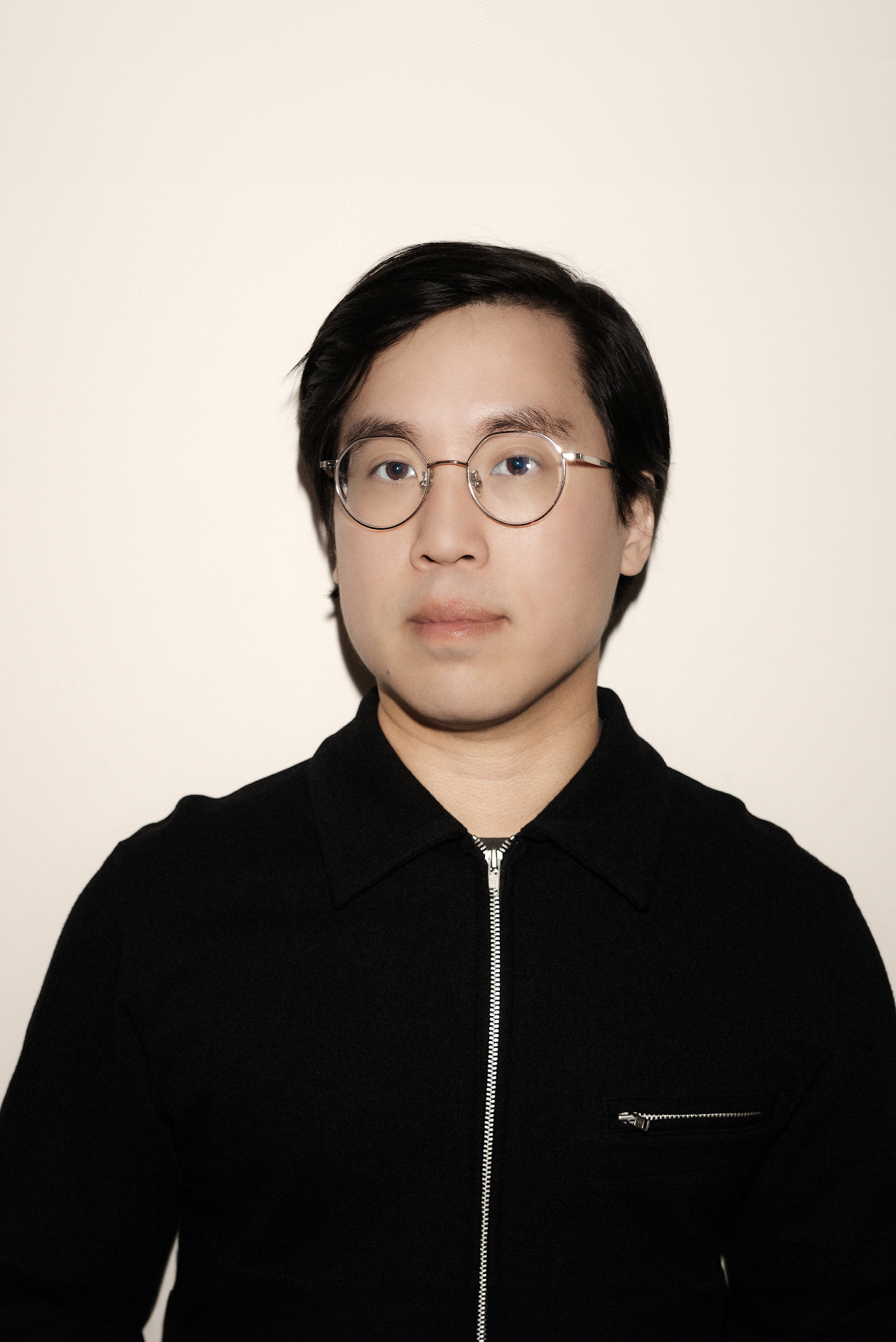

“Masturbatory Is a Compliment”: Tony Tulathimutte on Corniness and Rejection

The first time I applied to Tony Tulathimutte’s CRIT, the workshop he teaches from his living room in Crown Heights, I was rejected. Though at that point he was already the published author of a novel, Private Citizens, and the recipient of the prestigious Whiting and O. Henry Awards, he is humble, calling himself “literally just some guy” on the class billing. Still, I was crushed. “As always,” he wrote in the form email I received in July 2021, “rejection means nothing, and I encourage you to apply again…”

A clever and well-intentioned lie from a man who has thought obsessively about rejection for at least the last thirteen years. Indeed, if there is a leading scholar of rejection at work in American fiction today, it is Tulathimutte, whose second book, literally titled Rejection, is out from Harper Collins today. In the collection of linked stories, he plumbs the bitter and hardhearted, the burned and beleaguered, the scorned lovers and narrow-shouldered incels that haunt our modern world, both online and off. At risk of being too Tony-pilled: it is a hilarious, disgusting work of genius, proving outright, as he puts it below, that “masturbatory is a compliment.”

I never bought that “rejection means nothing,” and I certainly don’t after reading this book. But as for the rest of the sentence: I did apply again. From rejection, redemption; if only the characters in his book were so lucky.

———

ABRAMS: I see the book on your shelf right now. Does it feel different now that it’s done and you can’t change it?

TULATHIMUTTE: I’ve noticed this phenomenon among some writer friends. After they get the physical copy of their book, they’re stricken by this belief that they’re going to die. Like, they won’t leave their house because they think they’ll get hit by a car.

ABRAMS: Seriously?

TULATHIMUTTE: Especially for a first book. You feel like, “I’ve waited so long for this, I’ve wanted it so badly, so this can’t be real. It’s going to be taken away from me before it comes out.” So they sign the book deal and then get the fear of god in them. I don’t think it works on me because I just kind of want to die. It’d be too good. So it won’t happen.

ABRAMS: Well, I loved the book. I have the problem of a horrible attention span. I can’t read fast anymore because my brain is rotten from the internet or whatever, but I read this book in 24 hours. I literally could not put it down. And I know from what you’ve shared that that was not the case when writing it. It took a long time. Could you talk about why?

TULATHIMUTTE: There is this interesting mismatch between the subject matter, which is usually presumed to be ever-changing and disposable and relevant for a window of a week or two, with how fucking long it took to write the book, which was about 11 years. I finished the first draft of “The Feminist” in 2013. I started writing that in 2011.

ABRAMS: Your book could have a bar mitzvah. That’s crazy.

TULATHIMUTTE: My book’s not circumcised. But part of why I take a long time to write is because I’ll write something and then return to it in a couple of weeks or months and not like it anymore. I feel like if I spend a long enough time on something, then it time-proofs it a little bit. But the problem with that is I’m always updating. And those updates have ramifications elsewhere in the book. It’s miserable. But eventually, you think of it not as a process of hitting some sort of ideal state of completion but a point at which you just surrender to this torturous process. If the work that you’re doing is yielding diminishing returns, then that dictates when it’s done for me.

ABRAMS: You mentioned the moving target of your own tastes, and I think that’s a pretty good segue into the subject matter of the book, which is rejection. How did you land on all of these stories being themed around rejection? And what are you bringing to that subject?

TULATHIMUTTE: This is the exact question I’ve been dreading for months.

ABRAMS: I’m sorry.

TULATHIMUTTE: I guess, to answer directly, the topic landed on me. I didn’t land on it. Without getting into the grotesque details of my personal life, this is material that I have a hard time working with because it’s inherently undramatic. I resisted it for a long time before eventually caving and deciding to go forward anyway. The essay “The Rejection Plot” is something I wrote alongside the rest of the book. It was intended to be part of it for a long time, and was me trying to think through how to dramatize something where nothing happens.

ABRAMS: In all of these stories, plot doesn’t function with a traditional kind of forward momentum. But there’s plot in the sense that the rejection reshapes this character’s opinion of themselves. Do you think that rejection hardens you, making us crueler and sadder?

TULATHIMUTTE: Well, I think you put your finger on my solution to this sort of narrative problem of stasis, which is that instead of a plot development, you have a character development, right? The transformation of this character in the wake of one or several rejections is the general approach for at least the first three stories. But I would actually disagree that it hardened the characters. I would say that it tenderizes them. Rejection makes you neurotic because you’re scrutinizing yourself through the imagined lens of how somebody else perceived you and why they decided to reject you. That’s the engine of the character development. You either have a character like Craig in “The Feminist,” who is constantly doing this market research as to why he’s failing and coming to the wrong conclusions about it. Nonetheless, it hones him into this ideological position that’s very different from where he started. Versus somebody like Alison in “Pics,” who becomes jaded to the point where she feels numb because she’s felt everything that there is to feel.

ABRAMS: That’s interesting, the word tenderizes implies you’re taking a beating. But you take these pitiful characters and you don’t let them remain objects of sympathy, really.

TULATHIMUTTE: I’ve noticed that, implicitly at least, a lot of fiction is about empathy. It’s about the presumption that the more you get to know somebody, the more you’ll find in common with them and relate to them and feel for them and so on.

ABRAMS: What if the opposite of that was true?

TULATHIMUTTE: Definitely. I mean, that’s the impetus of “The Feminist.” You start to become more and more estranged from the character as he develops, over the course of these repeated rejections, a sort of personality theory. One funny thing about rejection is that every time you’re rejected, you find yourself cross-referencing the latest one with the ones before it. You’re thrown back into the past, and that process can take you so far away from the actual facts because you’re reacting to something inside your own head. It is an extremely private experience that’s hard for people who are not going through it to understand or relate to.

ABRAMS: It’s interesting, because you said that you don’t think of these characters as being hardened, but you have to inure yourself to the writerly world.

TULATHIMUTTE: I mean, it’s possible to be inured to literary rejections because you get a greater awareness of the fact that it has nothing to do with you or your work.

ABRAMS: But isn’t that true of a lot of romantic or social rejections too?

TULATHIMUTTE: Maybe. But you actually never know.

ABRAMS: Can you speak to how you landed on the types of rejection that you included, and what you felt like the driving force of the character development was in all of them?

TULATHIMUTTE: I started with “The Feminist.” The first three stories sort of form a trilogy. They’re written in a similar style—present tense, third person. So I felt like I needed to pivot. The idea of romantic rejection develops along a continuum: somebody who gets rejected a lot over the course of his life and is never accepted; somebody who’s rejected by one person who’s important in their life and can’t get over it; and somebody who is accepted but has so much internalized rejection that he cannot accept the acceptance. After that, I had this three-dimensional edifice. I wanted to go into a fourth dimension, so I made a story that was form-driven. It’s a Reddit post in the first person, and it’s about somebody who never faces rejection.

ABRAMS: Did you have to fight to keep that form?

TULATHIMUTTE: Well, this is interesting because the original form was very different. When I was conceiving of it as a book around 2013, I wanted to get at the topic of rejection from every imaginable angle. And fiction was just going to be one small part of it. There were going to be a lot of essays. There was also going to be a glossary. There were going to be logic puzzles, a piece that was written in the form of this like, Wittgensteinian set of propositions. There were Q&A type jokes. But I didn’t know how to corral all of that stuff. The non-fiction part got cut. It was about 20,000 words when I was finished with it. And at that point, the fiction part was almost four times longer than that. As you know, I think a lot about form in terms of driving or shaping a story even before I know what it’s about. That helped me a lot with generating material. But eventually I wanted something that was fun to read and didn’t feel like gratuitous gamesmanship.

ABRAMS: The book doesn’t read that way. Spoiler alert, it lands on this meta note where you write an imaginary rejection letter for the book itself. I was really struck by it not feeling navel gaze-y, because I think that’s hard to pull off.

TULATHIMUTTE: I’m also surprised that it didn’t feel navel gaze-y because that was sort of the intent. I don’t really like metafiction very much in general. But I also think that there’s no exhaustive approach to fiction—it’s all about execution. You can rehabilitate any method. So my dare to myself was, “Can I do a version of metafiction that doesn’t feel…”

ABRAMS: Corny?

TULATHIMUTTE: [Laughs] Right.

ABRAMS: You defined corniness in almost every class. And I think it’s a really useful exercise, especially for this book. Could you talk about that definition?

TULATHIMUTTE: I’ve been working for a long time on an essay about corniness because it’s such an occupational hazard for writers. I’m not even sure I’ve arrived at a really satisfactory definition, but the way I think about it right now is that feeling when you sense that the writer has taken for granted the validity of the effect that they’re trying to achieve with their work and is really overconfident in having achieved it. You see this when it comes to dad jokes, for example. “Why didn’t we invite the mushroom to the party? He’s a fun guy.” And then the person starts elbowing you in the ribs, being like, “Huh? Come on.” And there is this coercive feeling to it where—

ABRAMS: You, as the reader, are being forced at gunpoint to laugh or cry.

TULATHIMUTTE: Right. And the same goes for certain kinds of unwitting melodrama. Or a performative vulnerability where it’s like, “Hey, I was just really open, now you have to clap for me.”

ABRAMS: For me, that brings up another part of the form: you included emojis. Those are choices that people could read as corny, but it’s so well done. How did you execute that?

TULATHIMUTTE: It’s funny you bring up the emojis because apparently the book designers told me that there’s no font that includes all of the different symbols that I used in the book. I guess nobody at HarperCollins has ever done emoji reactions in a book before. So they had to come up with a bubble standard.

ABRAMS: That’s another place where you had to make a choice early on. Did it feel natural? Did you ever debate with yourself?

TULATHIMUTTE: Totally. The idea emerged from the same impulse to switch tracks to another plot line in the story. And so, I hadn’t seen anybody do a group chat in a story before. It’s probably been done, but I just haven’t seen it. It was actually partly inspired by Calvin Kasulke’s book, Several People are Typing. I really like the polyphonic feel of a group chat where you don’t have any of the dialogue tags or narration slowing things down. It’s just this barrage of multiple voices.

LEAH ABRAMS: Yet you were able to characterize all of the group chat. I hadn’t even really pegged Alison as a loser until I read her message and I was like, “Holy shit, I know this bitch.”

TULATHIMUTTE: It’s just because she punctuates, right?

ABRAMS: It’s that and her typing out “Haha.” But what about the “Am I The Asshole” post? How did that form emerge?

TULATHIMUTTE: That’s funny. Most people who read that story assume it’s an “Am I the Asshole” post because he is an asshole. But I wanted to leave it a bit open about which subreddit he was posting in. Originally, that story was a DM conversation on Tinder. It was about a guy who never gets responses from the people he’s DMing. So, it was already taking the shape of a monologue. I wanted another form that would accommodate that. And I just decided a Reddit post, especially the kind where people sort of show their own asses and are not aware of it, would be sort of perfect for this guy.

ABRAMS: You take these stock characters that we know on the internet to their logical extreme. And I wondered, where were you drawing from? What kinds of research did you do?

TULATHIMUTTE: This is not a research-heavy book. Private Citizens was, but this one is mainly just osmotic exposure to people and the internet. I relied on my imagination a lot more than I usually do. I made up a lot of stuff. And in terms of where it came from, as always the answer is that it’s just a weird katamari of people that you know and people that you have imagined.

ABRAMS: You take that question of whether it’s autobiographical head-on both in the second-to-last story and in the rejection letter. And I was remembering that you read “Ahegao” in the first Limousine.

TULATHIMUTTE: It was the first time I read from that story, I think.

ABRAMS: Well, what was it like to read that disgusting stuff out loud?

TULATHIMUTTE: Terrifying, honestly. Writing across difference is always scary, but it’s something that you have to do unless you are committed to only writing about characters who are exactly like yourself. I’m not gay, this character is.

ABRAMS: Actually, that was the question I wrote down after you gave that reading. And for those who haven’t read, the third act of this story is a very graphic custom order for a sex worker that the protagonist imagines. There were multiple people that left that reading like, “Wait, was that Tony coming out?” Or the people that didn’t know you were like, “I loved that gay guy who was celebrating pride.” So how do you deal with the assumptions that come with writing a story like that?

TULATHIMUTTE: Assumptions, I don’t really care. Sexuality is one’s own business. At the same time, I think that anybody can try to write about somebody different from themselves as long as the effort is made in good faith. I mean, I did take a couple of precautions in that I got a sensitivity read. But of course, I was still terrified that it was going to be misread. And that terror, when you’re really trying to get something right and you’re told that you didn’t, is material for the final story in the collection. Because that’s a form of rejection, right?

ABRAMS: Amazing that all of that can come from porn.

TULATHIMUTTE: That’s why “masturbatory” is a compliment. But I also want to do a good job of answering your question. Why does it have to be a gay guy as opposed to somebody more like me? The only honest answer to that is, I don’t know. I’ve thought about this a lot, and I think that part of my ability to fictionalize characters has to do with a sort of estrangement from my own experience. But that’s mostly an intellectual guess at it. The real answer is that’s how I pictured him, so that’s how I wrote him.

ABRAMS: One of the things that you said in class that stuck with me is that fiction can have a point, but it has to be more than the point. And I wondered if you had a point in mind while you wrote these pieces.

TULATHIMUTTE: Recently, my roommate sent me a really great quote from Edward Gorey, the goth illustrator. And it articulates the same point I was trying to make a lot better. He said, “Anything that is art… is presumably about some certain thing, but is always really about something else, and it’s no good having one without the other because if you just have the something it’s boring and if you just have the something else it’s irritating.” It’s the idea that a story is about something that’s nameable and identifiable, but it’s also gesturing to something outside of itself. That’s what gives literature its texture, [the fact] that it doesn’t mean the same thing to everybody. And this is why I’m dodging the question by quoting other people, because I don’t want to pin down a singular point at the risk of foreclosing other meanings.

ABRAMS: Well, ultimately, what I learned from you as a writer and teacher is that it’s an act of faith in your readers to leave that space. You don’t just trust that they’ll get to whatever contrived place you want them to, but that they’ll take it in some other interesting direction that you didn’t expect.

TULATHIMUTTE: And this even applies to a story like “The Feminist,” which I thought was pretty heavy-handed. I’m always saying that the best and the extremely fucking worst thing about fiction is that people will bring their own meanings to it. It gives a sort of richness, but it also means that you can get some really cockamamie readings.

ABRAMS: Speaking of cockamamie readings, how would you rank each character in terms of who you would want to hang out with?

TULATHIMUTTE: Unfortunately, I don’t really have to imagine this because I’m stuck with them. Nobody is at their best in the events that are depicted. So they all go on the shit tier, unfortunately.