LIT

How Venita Blackburn Wrote a Sci-Fi Novel About Sex, Grief, and Debt Collection

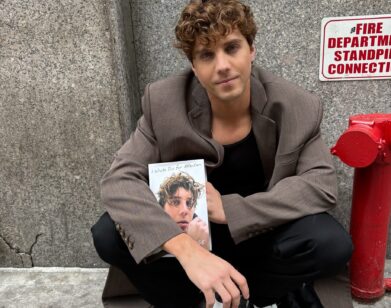

Venita Blackburn is one of our greatest living prose stylists. Her first two books, both story collections, are stuffed to the brim with some the best short stories I’ve ever read, and her highly anticipated debut novel, Dead in Long Beach, California, deploys Blackburn’s signature, crystalline, time-bending sentences to heart-stopping, stay-up-all-night-reading effect. The narrator of Dead in Long Beach, California is a collective, non-human “we,” an imitation of human consciousness after all humans are gone and the material world is only a digital memory. The “we” of the book remembers everything and everyone that ever existed, including Coral, our witty, funny, obsessive, graphic-novelist protagonist who finds her brother, Jay, dead by suicide in his apartment. In an instant, she decides that it’s easier for her to impersonate him online than confront his death.

Part of the magic of this book is that it is a portrait of devastating grief that possesses all the energy and momentum of a bank heist. Every time Coral communicates as her dead brother, it’s like seeing another gun, and by the end of the book, there are so many guns in the room that the anticipation of one going off is deafening. Between witnessing Coral’s grief-ridden present and memories of her family and Jay, the “we” also gifts us excerpts of Coral’s work in progress, a story about an extremely hot lesbian assassin debt collector who has an affair with a genetically modified lady scientist named Anemone. It was an utter joy to talk to Blackburn about this expansive, singular book on a Zoom call earlier this week. Blackburn, wearing her signature, gold-rimmed, rose-colored glasses, talked to me about how money feels, the absurdity of debt, and reaching for sex in the wake of death.

———

RITA BULLWINKEL: Oh my gosh, Venita. I am so excited to be here with you talking about Dead in Long Beach, California.

VENITA BLACKBURN: Thank you for doing this. This is great.

BULLWINKEL: Black Jesus and Other Superheroes and How to Wrestle a Girl are two of my favorite books I’ve ever read. And Dead in Long Beach, California, I just gobbled it whole in one sitting. I really feel like it is a book of science fiction. How do you feel about that genre camp?

BLACKBURN: I don’t think about genre like that, so I don’t approach any kind of work with one tone or angle as the goal. I have to have the voice that matters to me. But for this one, I did have this intention of doing this sort of high fantasy sci-fi, speculative kind of world that was tethered to our current modern world in a way. And as I kept going, I figured out, “Oh, the thing that’s nagging me, the thing that’s most hard to write is actually the part that’s closer to reality, and that’s the part I need to start investing more of my energy in.” That was a turning point during the early drafting stages, where I had to readjust the proportions and the vision and the scope. But I always knew it was going to be a little bit out of this world. Of course, the original title was “Lesbian Assassins at the End of the World,” so I was definitely going to reach far beyond what we know in this tangible universe. So that was fun to write, especially during the pandemic, when I was very disconnected from humanity. I wanted to be someplace safer, someplace where I understood everything, where I knew what was going to happen. So I started to get invested in that process and, apparently, that is a pretty cross-genre kind of way of looking at a story.

BULLWINKEL: Something that I loved about the narrator is that they use this phrase, “This is what we know for sure,” which felt like such a relief. This book is about so many things, which is what just totally electrifies me about it. It’s certainly about grief, but also about how money feels. Was the feeling of debt and the feeling of money something that you were consciously circling around?

BLACKBURN: I’m always consciously circling around this. I’m always looking at my retirement funds.

BULLWINKEL: Me too.

BLACKBURN: Also, I have a personal fear. I have lots of phobias. I have a mushroom phobia. And I don’t know what this phobia is, but the fear of debt should have a classification. It’s a very real thing for me. There’s something really constraining and terrifying about owing someone something. It reminds me of the fragility of my existence, where anything can be taken away at any moment based on some calculations, some numbers, fluctuating interest rates. These are horrifying circumstances. So, to me, debt really is just a highly specialized agent chasing me with the gun at any moment, so it created that world. But also, it’s not that far away from how we live, right?

BULLWINKEL: Yeah. The language of the mortgage, if one reads mortgage loan documents, is the language of the breaking of the legs. It is fully like, “This is the order in which we will repossess your belongings.”

BLACKBURN: The concept of property, too. People put a lot of faith in property as this foundational element of civilization, where you have to have this concept in order to motivate people to act and contribute to the world because this is the thing that’s promised to you.

BULLWINKEL: It’s a totally bizarre, collective delusion because what even is it? It’s not even something you can hold.

BLACKBURN: It is an invention, and it’s a complicated invention. It’s the hammer, the light bulb, the gun, the concept of property. It’s just one of those things that we’ve made up and it sticks with us. Once you have it, you can’t let it go. And also, when a culture encounters another culture that does not have that, it’s about trying to convince each other that this is a better way of life. Of course, whoever has the most physical might will be the one that absorbs the other.

BULLWINKEL: This whole book has this feeling of impending disaster, like when Coral is not going to be able to sustain the lie that she’s telling about her brother. And in the midst of that, there are these really affecting, anxiety-ridden scenes, both in memory and in the present, like the scene with Summer at the casino. Casinos are these theaters of the absurdity of money and debt. You don’t know if it’s morning or night. How did you think about those casino scenes?

BLACKBURN: I love your questions, Rita. Nobody talks to me much about the money aspect that’s going on in the book, but I love it. I actually enjoy gambling, that’s one of my bad vices. But also I haven’t quite figured out how to write the people in the casinos. I’ve been observing them since I was 21, and I know the fever. It’s akin to addiction, it changes the brain and all of that kind of stuff. I don’t know how to write about that kind of person yet, but the environment itself is just too good for me to let go. It’s one of those fixed places, almost like a moon or something, and it was a good environment for the situations of these characters.

BULLWINKEL: That drive to the casino to meet Summer totally had heist energy to me. Another thing I’m dying to ask you about is how you understand narrative time. One of the things that I’ve always admired about your work is the way you dissolve and bend time back on itself and seem to compress it and expand it in this completely insane suspension-of-physics way. So I’m interested in your perspective on linear time.

BLACKBURN: I think flash fiction needs to be really good at expanding small moments. But also, it can do the opposite, it can take huge lifetimes and compress them into a page. It’s really hard to do, although it looks easy when you do it, but that’s one of those big writing goals and practices. I have to remember the motion that will achieve that sense of movement and time. The mind is not linear, we don’t think that way. Memory doesn’t work that way. And I know this because of my own way of thinking. I’m so bad with actual dates and times. It’s always in flux. So that sense of movement and fluctuation, that kind of fluidity of memory, that’s me, that’s how my brain works, so I’m always going to have to embrace that when I see it on the page.

BULLWINKEL: Yeah. I have so many questions.

BLACKBURN: Take your time.

BULLWINKEL: Okay, this book is really sexy….

BLACKBURN: It’s kind of horny in a weird way, yeah.

BULLWINKEL: It’s very, very funny, it’s very sexy, and there are these pretty explicit parallels drawn between grief and desire. That seems so true, and not well-tread.

BLACKBURN: I think we just probably don’t articulate it as much, but it’s definitely there. I would call this one kind of a love story on top of a grief story. There is that thing that happens to the body when you’re getting close to death—you reach for life, you reach for something that’s going to feel electric, and of course, sex is an obvious way of doing that. Expectations of grieving and the real thing are very different. For this character, I thought I was going to go in the real direction and not just in the present, but also in the past and in the future as well, and how that circles around itself in the body. So it’s kind of silly. The fan fiction scene was extra silly. I like to have moments of lightness and play no matter what the topic is, because that, too, feels human. We’re not these beings that isolate and get locked into a certain emotion. We have to be able to see all the beads of ourselves.

BULLWINKEL: When I think about your prose on the page, and why I think you are one of our great living stylists, I think about your lists. You have these electric lists that I’ve never seen anywhere else in literature that almost read how I’m pretty sure relational aesthetics work—this idea that if you put two objects next to one another, they have to have meaning, and the power of the artist is in picking the objects to place next to each other. So, how do you make them?

BLACKBURN: Thank you. I’ve never heard that term about art. Say the term again.

BULLWINKEL: The term is relational aesthetics.

BLACKBURN: I love it. Because that’s what it is. I want to make sure I have an eye around the world, for things that you can find in different parts of earth, not just one region, not just Compton. And then, I want to blink into the abstract just for a second, give me a thing we can’t see but that we feel, and then we bounce around and they get closer and closer, the abstractions in the sentence. And of course, the final thing is vanity. Because I was raised Southern Baptist, a lot of scriptures are in my brain. There’s some very beautiful books in the Bible that I think constructed a lot of the way I look at language. And Ecclesiastes has a lot of lists. Psalms and Proverbs, they have that rhythm and that poetry. I do appreciate that you appreciate the lists, Rita, because I do think about them. It’s not just a throwaway thing.

BULLWINKEL: I love them. So much of what I love about your work, Venita, and you can see it in these lists, is the way you dissolve linear time, because you really are doing something that only a book could do. Film can do some things, but it’s so voyeuristic and linear.

BLACKBURN: [Laughs] Don’t ruin my film deal. I don’t have one, but I’ll take—

BULLWINKEL: Where’s the Dead in Long Beach, California movie? I’m personally waiting for it.

BLACKBURN: It’d be weird to do, right? You’ll have to have some kind of weird voiceover and all that kind of stuff that is not quite what it’s like to experience it on the page. So I’m with you; some things only work in a certain kind of form the best way.

BULLWINKEL: This book deals pretty heavily around the archetype of the mom, the good mom or the bad mom. Maybe it’s something that I’m circling in my own life and I’m projecting, but it feels like it’s partly about mothers.

BLACKBURN: Oh, definitely. I write about dysfunctional mother-daughter relationships and also the complex layers of femininity and tortured femininity and things like that. That’s a theme that does pop up a lot in my work. I have a good mom. She was my best friend, so this is not autobiographical in that way. But I have seen bad mothers up close. And I’ve also seen ordinary women that are just being alive, being human. But, by our standards, they would be considered bad mothers, and that fascinates me too. So I always have to write about the things that trouble me, that I’m trying to understand, that maybe don’t have any clear rules to them. That complex, dangerous mom or dysfunctional maternal instinct, that’s a powerful one that I’m always circling back to. And I think that’s my self-imposed sense of therapy practice or whatever it is to try to keep finding some grace in the horror. I keep writing it over and over again to get to that point. It is one of those elements of life and people that really nag at my brain. BULLWINKEL: Well, I’m so grateful that I got to spend this time with you. I feel like we’ve only ever hung out in crowded writer’s conferences, which have good and bad things about them.

BLACKBURN: That is a thing. We’re going to hang out in March.

BULLWINKEL: I’m excited. I’m just forever in your debt.

BLACKBURN: No, not at all. Remember, we don’t believe in debt, just friendship, just compassion.