Screen Time with Yvonne Rainer

In 1966, while recovering from major surgery, Yvonne Rainer directed her first film, Hand Movie, from the confines of her hospital bed. Heading eastward to Manhattan from her hometown of San Francisco in 1956, Rainer soon abandoned studying the Stanislavski acting method to train with Martha Graham. Eventually, she fell in with some of the most iconcoclastic artists of the era—Merce Cunningham, John Cage, and Robert Morris among them—and became a founding member of the Judson Dance Theater, the hotbed of avant-garde experimentation situated out of the Judson Memorial Church on the south side of Washington Square Park.

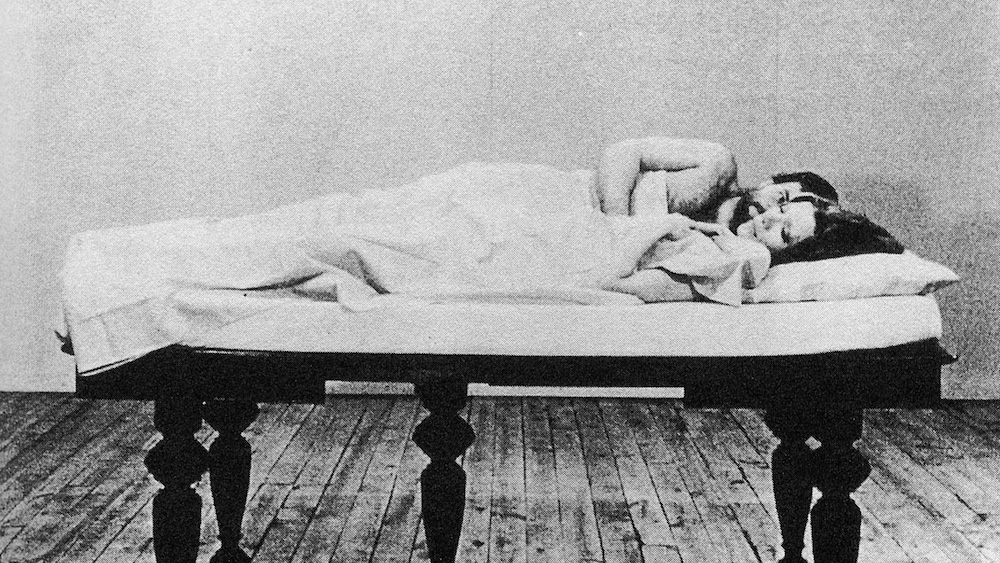

Rainer’s preoccupation with the modes of performance and her groundbreaking choreography, which revolutionized the history of dance forever, echoed Judson’s Cage-ian minimalist credo and eschewed dramatic stylings, favoring movements of the everyday and the banal. But by the late ’60s, Rainer was looking for other narrative options. Silent, running eight minutes long, and filmed by William Davis, a dancer and fellow member of Judson, Hand Movie depicts Rainer manipulating her palms, wrists, thumbs, and fingers against a solid backdrop in a manner remiscent of the ways in which the body moved in her composed dances. The burgeoning feminist movement and experimental film work being made by the likes of Andy Warhol and Hollis Frampton soon incited Rainer to leave choreography and take up film as her primary medium. (Rainer made her last film, MURDER and murder in 1996; she returned to choreography in 2000 when Mikhail Baryshnikov invited her to stage a performance for his White Oak Dance Project).

Starting tomorrow, the Film Society of Lincoln Center will mount a retrospective of the legendary artist’s film work, “Talking Pictures: The Cinema of Yvonne Rainer.” The series—which spotlights her seven feature films, including Lives of Performers (1971); Kristina Talking Pictures (1976); A Film About a Woman Who… (1974); and her early shorts alongside influential works, such as Maya Deren’s At Land (1944) and Laura Mulvey and Peter Wollen’s experimental feminist text Riddles of the Sphinx (1977)—is a tour de force showcase of Rainer’s own particular brand of écriture féminine. It examines politics, gender politics, heterosexual and lesbian partnerships, and of course, the heavy business of being a woman making art.

Last week, Interview called up the octogenarian artist while she was on Long Island’s North Fork.

COLLEEN KELSEY: I was reading a transcript of an interview that you gave for the MoMA archives in 2011. At the time, you said that you were a filmmaker between being a choreographer and a choreographer. How are you defining yourself at the present?

YVONNE RAINER: I’m a choreographer and ex-filmmaker, sometimes a writer. What else? Performer.

KELSEY: “Ex-filmmaker” seems pretty strong. Are you completely against making a film in the future?

RAINER: It’s unlikely. I’ve been out of it for so long, and I’m well into my eighties. I never did enjoy the production part of it. I enjoy calling myself a techno-dummy. [laughs] And I love working with dancers. I have a stable company who seem to enjoy working with me.

KELSEY: What first brought you to New York?

RAINER: My older brother knew these New York-born anarchists after the Second World War and I went to their parties and houses. They talked a lot about New York. And then I met Al Held in San Francisco, a painter. We got together and he moved back to New York and I went with him to study acting at the Herbert Berghof School of Acting.

KELSEY: Were you always dancing?

RAINER: No. I attended some concerts in San Francisco, but in my teens it never occurred to me that I could do anything like that. Then I kind of stumbled into this acting school in San Francisco, and I loved performing. They gave me bit parts. There’s a play called All the King’s Men that later became a film, and I was in the crowd scenes. My one short solo in it—I was up on a platform—I was the mother of the main character, and the lights came up and I was in this peignoir and I screamed, “You killed him! You killed him!” And the lights went off. [laughs] But I loved being in the spotlight.

KELSEY: I don’t want to talk about Judson too much because I want to get into your films—

RAINER: Yeah, thank you. [laughs]

KELSEY: But what was that creative switch for you? What was the first inkling that you wanted to make a film?

RAINER: The second wave feminist movement came along in the late ’60s, early ’70s, and I began to be restless as a choreographer. For ten years I’d made dances, and the kind of dancing I did, I began to feel had limitations. I didn’t make it an expressive kind of dancing that dealt with a wider range of subjects. I had been exposed to European art films and the New American Cinema, structuralist cinema, and I just saw film as offering greater possibilities for my interests. I got a Guggenheim [grant] in 1969 and I began to make haphazard scripts dealing with a group of dancers. I made a performance and a film on this $10,000 grant. So I was launched into filmmaking—the story in short.

KELSEY: Do you see short films such as Hand Movie as experiments or sketches?

RAINER: Yeah. I had made these short films. I don’t think I used the camera myself. I was in the hospital, and one of these films [Hand Movie] was just of my hand, a close up of my hand moving. I had had surgery. I’d been seriously ill. A friend came with an 8mm camera and filmed this close up of my hand moving. I used that—it was projected to one side of a dance I made, The Mind Is a Muscle. I made about five or six of these short films. Ten minutes, the roll of 16mm film determined the length. I was already thinking about film in the late ‘60s.

KELSEY: When you started making feature films, starting with Lives of Performers, did you have any indication of how inherently political your films would become?

RAINER: I should say that feminism gave me permission to deal with my own emotional life and put it up front in certain ways, or use film as a way to examine, at that time, my own heterosexual experience. Lives of Performers was the beginning of that kind of investigation. But also, the film was influenced by the aesthetics and structures of experimental film as that was taking place at the same time. Hollis Frampton was a big influence on me at that time.

KELSEY: And what about the influence of someone like Warhol, and his work with duration and silence?

RAINER: Warhol, definitely. The late ‘60s, the idea of duration. I always like to cite John Cage’s mantra, “If you can stand it for two-minutes, try it for four.” In fact, when I look at some of those early films of mine, I think, “Oh my God. Cut it, cut it.” [laughs] The general sense of duration has changed over the years, my own sensibility with it.

KELSEY: How do you feel watching some of these early films?

RAINER: It depends on the film. My favorite are Lives and the last two, I guess. I never made another film like that first one, which had no synced sound. The reactions of the performers themselves, who were looking at a rough cut of the film and laughing and making comments. If you look at the seven films, you can see an evolution towards more conventional techniques like using professional actors and reverse shot and other cinematic ploys that lend themselves to Hollywood illusionism. Even in the last film MURDER and murder, there are devices that are constantly undercut in the characterological illusion of the film.

KELSEY: You’ve used Sontag’s term “radical juxtaposition” when talking about your films. What does that mean to you?

RAINER: Briefly, it’s about putting two things in the same frame that don’t match, a voiceover that does not match what you’re seeing. So two parallel trajectories that you have to follow at the same time. Also, I was always drawn to devices that made for unpredictable changes and cuts. From jump cuts, to changing the subject entirely. I guess you might call it Brechtian—using conventions to draw the spectator in and using distanciation devices to make you self-conscious looking at a film. And having a critical perspective on it. I once had a conversation with [film theorist and filmmaker] Peter Wollen, and I asked him, “Do you ever lose yourself in film, even a Hollywood film or a traditional narrative film?” And he said, “Never.” [laughs] He doesn’t allow it. But I was very interested in using some of these traditional devices, but undercutting them, undermining them at the same time. For instance—even in my second film—you’ll hear a voiceover and then I cut to an intertitle that continues what that voice has been saying. That isn’t exactly radical juxtaposition, but I can’t think of another example at the moment. Maybe you can.

KELSEY: Last year I interviewed Babette Mangolte about her work with Chantal Akerman; you worked with Babette on a number of films as well.

RAINER: She taught me everything about filmmaking. I owe a lot to Babette. She had worked on 35mm films in France, and she came with all this knowledge and immediately jumped into experimental filmmaking in New York. I met her through the film historian Annette Michelson, and she was instrumental in my first two or three films. In fact, in Lives of Performers, the dance part of it, she filmed and edited. I didn’t have much to do with that. But then we worked together on the editing. It wasn’t until maybe my third film that I edited by myself. I learned a lot from her.

KELSEY: Did you feel a connection between choreographing dance with the body versus “choreographing” a film through editing, working with actors, et cetera?

RAINER: Here the element of duration comes in very much. When do you end something? I’m thinking of the beginning of my current choreographic endeavor, where it begins with the units in movement with little abrupt changes of direction and style and movement. Harmony was never one of my strong suits or interests. Changing the terms constantly is what interested me. Although like Journeys from Berlin/1971, there are these long passages of narrative about German history in the ’70s. There’s that continuity, but it’s conducted by rolling titles. As soon as I get into images and language, that’s a whole other story, and radical juxtaposition can operate, you might say. Like in Journeys, the helicopter perspective of the Berlin Wall while you hear two people, a man and a woman making dinner and talking about Baader-Meinhof. Everything gets connected. That screen is very hard to disrupt.

YVONNE RAINER: TALKING PICTURES RUNS UNTIL JULY 27. FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT THE FILM SOCIETY WEBSITE