The Children’s Hour: Valérie Massadian on ‘Nana’

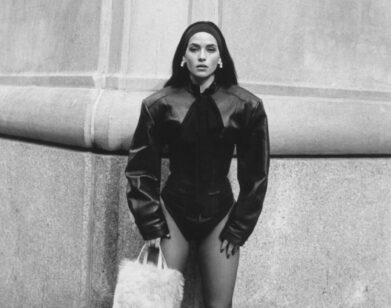

ABOVE: KELYNA LECOMTE IN VALÉRIE MASSADIAN’S NANA.

Nana, the first film from director Valérie Massadian, is one of the great debut films of the past year, a quiet, minimalist exploration of childhood in all its elusiveness. It’s anchored by the non-performance of Kelyna Lecomte, in the titular role, as a young girl left alone to fend for herself after her impatient mother (Marie Delmas) leaves the small cabin they occupy on the outskirts of her grandfather’s pig farm, and never returns. The film is intimate without being sentimental, and evokes emotions out of its unusual rhythms and spatial configurations.

Interview spoke to Massadian on the phone from Paris about her photography experience, working with children, and using nature as a character.

CRAIG HUBERT: You come from a still photography background. What is the difference for you between still photography and film, and what did you want to do with film that, maybe, you couldn’t do with photography?

VALÉRIE MASSADIAN: Life. [laughs] Photography is a dead moment. That’s it. It’s like a grave. It can be a real strength. What’s wonderful about cinema is that it’s the exact opposite, it has no boundaries. What’s not in the picture does exist. The fact that light can move—it can be sunny, and when there’s a cloud, you can see it. Which you rarely see in films.

HUBERT: I noticed that in the scene where Nana is sitting on the couch outside the cabin, you can see the light naturally moving across the screen.

MASSADIAN: Even in the woods, when she is eating the cookie. Right. The limit of photography is that it doesn’t let life in.

HUBERT: You’ve worked with Nan Goldin in the past. Has anything about her work, or the way she works, influenced your filmmaking?

MASSADIAN: The thing I really learned from Nan was the concentration of being in front of someone, and being with someone. This film wouldn’t be what it is if I hadn’t done it with Kelyna [Lecomte], the little girl. There’s not one word, one gesture—nothing—that I imposed on her. We played. Kelyna still doesn’t understand, though she saw the film three times and she saw more than most people see in each shot. If I don’t have my camera, she’s like “Where’s your camera?” [laughs] For her, and for me, it’s completely related to spending time together, questioning things—life.

HUBERT: Why make a film from the viewpoint of the child?

MASSADIAN: That was where I was the most comfortable, because that was where I could be on the ground. [laughs] It was great. No, because for me, film is physical or emotional before being intellectual. I mean, there are really heavy questions with a child—she’s a four-year-old, they ask you about death, all the heavy philosophical questions, and because I spent so much time with her I had to try to give answers. But I didn’t have to explain any psychological questions, like with an adult, which don’t interest me in films, at all. That’s your problem. The way I built the film is to leave open space. I see films as dialogues, not as monologues, which most of them are today.

HUBERT: Is the difference between working with children and adults that the adults often require some psychological understanding of the character?

MASSADIAN: The girl who plays the mother is a dancer and actor. The grandfather, it was exactly like working with Kelyna. It was exactly the same. He’s so anchored, so centered as a human being. We would talk to each other, because I was behind the camera—I could have made a completely different film, which would be them and me, a documentary. It would be interesting but I didn’t want to do that. With Marie [Delmas] it was completely different. It’s not that she needed psychological blah, blah, but she was an actor—it was very complicated for her, and then for me, that she would let go. There was a real one-to-one because I was filming them; I was always there in the space. It was really an ongoing link between us. For me, it’s complicated. I see an actor doing it; I see them trying to do something. Basically, I don’t want them to do anything. [laughs] So yeah, the work was completely different. It was actually the exact opposite: working with Kelyna and the grandfather was an act of love, and with Marie, it was confrontation. All the tension I used in the film to build her character—but at one point I was about to say stop, fuck it, there’s no mother, we’ll do something else. [laughs]

HUBERT: When you mentioned the tension, I was thinking of a very specific scene in the film, one where the mother and daughter eat together in the cabin. It is played out in an extremely long take, and tension goes back and forth a number of times throughout what is a very quiet scene.

MASSADIAN: A completely quiet scene! In this scene, the only thing I did was forbid her to help Kelyna. First, time really creates the tension—when she starts not helping, the girl has to figure out how to do it herself; because it lasts too long, it becomes something else.

HUBERT: Maybe we can discuss the rhythms of the film. You use extremely long takes, as well as a steady, mostly static camera that keeps its distance most of the time. There are no motions toward naturalism or documentary-like realism.

MASSADIAN: Well, to me, it’s not a documentary at all. The only documentary parts of it are the words—the words are their words. That’s not their life – apart from Alain [Sabras] with the pigs, that’s his life. That’s why it starts the film—it goes from the world to her head. The distance was also because I knew what I wanted to look for—the relationship to death, solitude, the physicality of a child and how often they’re shown as fragile little things when they’re like monsters and are so strong.

HUBERT: [laughs]

MASSADIAN: They are! They’re fine; we fuck them up. [laughs] I knew, because I spent a lot of time with Kelyna, that I needed to give her space. Very often people say, “Ah, I expect her to cry, I want to see her close up because it allows me to have empathy.” Well, fuck you. [laughs] I don’t want to go there. Also, because of nature—to me, there are two main characters in film, her and nature.

HUBERT: Nature tends to engulf her in the film, because she is so small. It’s almost imposing.

MASSADIAN: The thing you’re talking about, for me, gives the film a real shift. At that point, it’s flirting with reality and not reality. It could be all in her head or really what’s happening. It’s playing with fairy tales.

HUBERT: I know the film was made in the community you grew up in. Do you see the film as personal, in any way?

MASSADIAN: I think when you film you’re looking, so there’s always something that has to do with you. Choosing to do it with Kelyna already says something, because it’s an animal I understand and I can relate to.

NANA WILL HAVE ITS NEW YORK PREMIERE AT THE MUSEUM OF THE MOVING IMAGE AT 5 PM ON SATURDAY.