Unmasking Isabelle Huppert

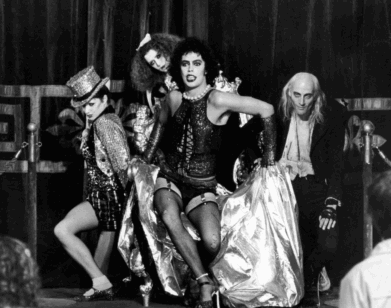

KOOL SHEN AND ISABELLE HUPPERT IN ABUSE OF WEAKNESS. IMAGE COURTESY OF STRAND RELEASING

At the age of 61, actress Isabelle Huppert has made over a hundred films. She’s worked with Jean-Luc Godard, Claude Chabrol, François Ozon, Michael Haneke, Wes Anderson, Claire Denis, David O. Russell, and avant-garde theater director Robert Wilson. As a winner of the Cannes Best Actress award (twice) and former President and erstwhile member of the jury, she’s one of the most visible dramatic actresses of her generation. John Waters, writing in Artforum last year, called her his “favorite actress in the world.”

Huppert has manipulated her petite, lithe frame (even at 5’2″, we are taller than Huppert) and her sculpted, patrician beauty into embodying some of the most charged, manic, and emotionally turbulent roles in cinema over her four decade-long career—a feat of not only talent, but also a certain fearlessness. They’ve included a self-mutilating, masochistic pianist (2001’s The Piano Teacher), a working-class woman giving illegal abortions in Vichy-era France (1988’s Story of Women), a homicidal postal worker (1995’s La Cérémonie), a mother in an incestuous relationship with her son (2004’s Ma mère), and an existential “expert” (2004’s I Heart Huckabees). But to hear Huppert tell it, when we meet with her at her hotel suite in midtown Manhattan, putting and shedding the skin of a character is just a “mask.”

In 2004, French filmmaker Catherine Breillat (Fat Girl; Sex is Comedy) suffered a severe stroke as a result of a cerebral hemorrhage. She pushed herself towards recovery, preparing a screenplay of her novel Bad Love set to star Naomi Campbell, and courted convicted conman Christophe Rocancourt to co-star as the male lead. Over the subsequent months, Rocancourt swindled Breillat out of nearly €700,000 worth of checks in her deteriorated condition. She eventually took him to court, won her case, and chronicled the experience in a book, Abuse of Weakness, which she has now adapted into a film starring Huppert as the filmmaker, Maud, and rapper Kool Shen as Vilko, Rocancourt’s doppelganger, opening this Friday for a week-long run at Film Society at Lincoln Center.

Breillat sets up an icy, penetrating account of the unsettling and perverse power play between the two of them, which vacillates, on both sides, between infatuation and exploitation. Huppert’s bold embodiment of Maud’s physicality and wavering mental state—from the opening scene of her lifelessly jerking out of bed, to her slowly regaining speech, continuing grappling with her cane and heavy orthopedic footwear, and her erratic treatment of Vilko, from nonchalantly signing him checks to quite, literally, attempting to push him out of her life—is a study on lucid and altered states.

Huppert, in New York for The Sydney Theater Company’s production of Jean Genet’s The Maids (in which she co-stars alongside Cate Blanchett and Elizabeth Debicki), which ends its run this week at the Lincoln Center Festival, will next be seen in Ned Benson’s The Disappearance of Eleanor Rigby with Jessica Chastain and James McAvoy and is set to start filming Norwegian director Joachim Trier’s Louder Than Bombs, with Jesse Eisenberg and Gabriel Byrne, this fall.

COLLEEN KELSEY: Maud is a fictionalized, abstracted version of Catherine, but how close do you think it was to her own personal experience?

ISABELLE HUPPERT: I think it’s very close, actually. The film is based on the book she wrote not long after the story happened to her. It’s hardly fictionalized. She’s a filmmaker in the film, and Catherine is a filmmaker. She has kids. I think the most fictionalized element might be me, because, obviously, I’m not Catherine. So, there comes fiction from my presence on screen. I was able to build up my own story and build up my own character with my own self and my own reactions, so it really becomes a film and not a documentary. Catherine puts it so nicely. She says, “It’s a film from me, but it’s not a film about me,” which says it all. It’s really her statement as an artist, and not a realistic documentary about her life. She really meant it as an object, a cinematic object, and that’s how she wants people to watch the film.

KELSEY: Considering how personal this process could be for Catherine, translating what her experience to a product onscreen, did you notice if making this film was particularly healing or cathartic for her?

HUPPERT: From the beginning, writing the book was already a healing process. She was always very energetic, very strong, even right after the stroke happened to her. From the very beginning she really wanted to survive, first of all, and then to recover as much as she could. For her, going on was being a filmmaker. Going on with her creative life was really a part of the surviving process.

It was really, really important for her that she was still able to make films. She still is, obviously. She has the same kind of life as she had before [the stroke]. You have the physical story that happened to her, and then came this encounter with this man, which was just unbelievable. It certainly helped her to try to understand, even if there was really no answer. At the end of the film she says, “It was me, but it wasn’t me. It was me, but it wasn’t me.” She goes back and forth. There is a black hole, that she can’t really understand why she did that. In this questioning, the answer is implied. You don’t know why you do things, but you do them. That’s precisely what it is about.

KELSEY: How do you define the relationship between Maud and Vilko?

HUPPERT: It’s sort of a childish relationship in a way, sort of adolescent, because there is no sex. There might be a sexual attraction, but it doesn’t go all the way. It’s childish, it’s playful, it’s perverse sometimes, because he understands perfectly how to control her, and she understands how to control him. It’s a power game most of the time. Obviously, yes, there is an attraction, but the attraction does not only come from the weakness. Yes, she’s dependent, because when you have this kind of physical disability, you feel dependent on anybody. But it’s not only that. He’s dependent on her too, because he understands she’s an intellectual. She has cultural and social tools that he doesn’t have.

KELSEY: I found the mutual infatuation very interesting because initially she wants him as the character in her next film, so he has this appeal as a muse or something, and it seems as if he is her possession at first.

HUPPERT: As a director towards an actor, you have control. She writes him all these checks and she pays the money and it’s like there was a veil on her consciousness. She doesn’t want to understand. I think that from the very beginning she does understand—you give money to someone, you understand what you do. But there was a veil that she doesn’t want to uncover. She doesn’t want to face reality. I don’t know if it’s so readable in the film, but there is one moment when she really realizes. It’s on Christmas, when they’re all sitting by the tree and he offers a handbag to his young wife. I insisted that at this moment there should be a close-up. Catherine was not going to do it. But as an actress, I felt that that was a very important moment. When she sees it, she understands clearly. As long as the money exchanges go between her and him it’s okay, but all of a sudden it goes through another person—

KELSEY: She sees where it’s going.

HUPPERT: She watches the bag and then something comes to the surface of her consciousness that something’s gone wrong. It clicks quite quickly. All of a sudden she wants the money back.

KELSEY: Throughout the film, I was so curious about the mental space that Maud was in. Sometimes it feels like she’s almost in a dream, especially with all of those shots of her in bed. Did you do any research about the psychology of how people are after they come out of stroke, what’s going on in terms of cognitive function?

HUPPERT: I didn’t. I thought the fact that sometimes she’s a bit in a limbo comes from the fact that she had a stroke. That can also be an explanation when you do something without really thinking, or your connections are not so sharp in a way, so at some point I thought, “Okay.” But I didn’t really use that consciously. It was more of an afterthought than a strategy in my building of the role.

KELSEY: So in terms of preparing for a role, is it mostly emotional for you and less about research?

HUPPERT: Yes. It is and it is not, in a way, because if you are too emotional then you don’t have enough distance to understand what you do. It’s a very strange type of emotion. I think no matter what you do, on screen or on stage, it’s a sort of delayed emotion. I mean, it is an emotion, but you are not quite in it, because you do it, so you can’t be in it by doing it. Otherwise you will be overrun by it and then you will not have any distance and any control on what you do. It’s like what she says at the end, “It’s me and it’s not me.” Most of the time, you can find a way for roles to be exact metaphors of what you do as an actress. It is emotion, but is not emotion. It’s a paradoxical scheme of what you do.

KELSEY: Something that I’ve always appreciated about Catherine’s films is her distinctly female point of view and her telling of female-centric stories. What’s her approach like on set as opposed to other people you’ve worked with?

HUPPERT: First of all, she’s been a friend of mine for years, but it’s always a bit weird being very friendly with someone and then all of a sudden you find yourself in a totally different position, she as a director and me as an actress. Even though we are great friends, sometimes you have to adjust because it’s a separate relationship all of a sudden. She’s known for being very stubborn and sometimes very authoritative. She has a certain ideal about what movies should be, which is her ideal, not necessarily what movies should be universally, but that’s at least what she thinks. Sometimes you have to argue and negotiate. But it was a positive arguing. I understood because also she has the eye of a painter. She wants things to be exactly the way she thought about them to be. She has a vision, obviously, and it’s always interesting to be a part of that vision.

KELSEY: As an actress, how much of yourself do you surrender to a director?

HUPPERT: It’s a compromise. I don’t think I ever surrender, but it’s always possible to be a part of that vision and also to be the mask, in a way, because when you do a role, obviously you wear a mask, but behind the mask it’s yourself. The mask is there not by necessity, but because you are in the story, you say things, you say dialogues, you are in fictionalized situations. The story operates always like a shelter in which you can totally be yourself. But to what degree, nobody can tell—only you.

KELSEY: What do you think movies can tell us about real life?

HUPPERT: I think they say a lot, movies even more so than theater. It says a lot about the invisible, that movies are so fascinating. The camera lens is like a microscope that goes beyond the surface. It’s like you’re exploring a secret, so you explore the director’s secret, you explore the actor’s secret, and therefore you explore the universe’s secrets. [laughs] For me it’s a lot about that, about exploring the invisible.

KELSEY: Do you see a connective thread of all the different types of women that you’ve played throughout your career?

HUPPERT: Me. [laughs] I would say that would be what they have in common. I’ve played so many different women. In the dramatic roles I’ve done, there is a something that ties them to one another in the sense that they’re all survivors, not necessarily winners, more like winning victims, which I think is probably more close to reality than playing Amazons or Wonder Woman or things like that. I think that strangely enough, the comic roles allow you to display a bigger branch of what you can be. There are many different ways of being funny. I’m not sure that there’s so many different ways of being dramatic.

The choosing of a role is so difficult for me. That’s the real challenge: to choose the role, not to do the role. Once you’ve chosen them, the process is much easier. Some roles are easier to choose, some roles are more difficult because they are more daring. Sometimes you have to dare. Even Abuse of Weakness, when you have to do a physically diminished character, it’s not that difficult, but it’s a way of showing yourself. I pick someone like Erika in The Piano Teacher [2001], for example, it was a daring choice which I never regretted afterwards. Sometimes you have to go that far. If it wasn’t for [director] Michael Haneke I would’ve certainly been a lot more intimidated and I’m not sure if I would’ve dared doing it. Given that it was Michael, I knew what he was capable of, and I knew I was going to be protected. Even if you are protected, at some point you are also exposed. But it’s important to be exposed.

ABUSE OF WEAKNESS OPENS AT FILM SOCIETY AT LINCOLN CENTER IN NEW YORK STARTING THIS FRIDAY, AUGUST 15, FOR ONE WEEK ONLY.