The Sinister Side of Tickling

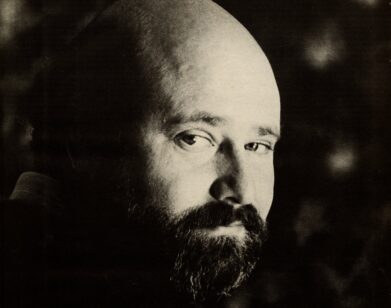

ABOVE: DAVID FARRIER IN TICKLED. PHOTO COURTESY OF MAGNOLIA PICTURES.

When New Zealand journalist David Farrier first heard about the sport of “competitive endurance tickling,” he was intrigued. It sounds, after all, like a game devised by a seven-year-old to torture his or her younger siblings. As Farrier started to casually investigate—watch a few YouTube videos, look at a Facebook page—things became increasingly incomprehensible. The framework of a competitive sport was missing—a method of evaluation, a clear objective, winners or losers—and yet a company named Jane O’Brien Media was willing to shell out thousands of dollars to fly prospective players to Los Angeles. Once in L.A., ticklers would be videoed in action. Competitors were exclusively young, male, muscular, and seemed to be predominantly white. The videos produced were bizarrely sexual, with one player tied to a mattress on the floor while the others sat on top of him, tickling his feet, stomach, arms, and legs.

With his friend Dylan Reeve, Farrier followed the tickling trail all the way to the lonely, fraudulent top. Tickled, the documentary they created, is absurd, disturbing, and sad. After debuting at Sundance and making the festival circuit—and being threatened by lawsuits every step of the way—Tickled comes out in the U.S. today. The story, however, is far from over.

“Tickling has been all consuming,” says Farrier. “We could have finished the documentary and that could have been it; you could have put it out there and hope it does well, but we’re hearing from so many people involved in this world that all of our time is taken up still talking about this film and concentrating on it,” he continues.

EMMA BROWN: How did Stephen Fry get involved? I see he’s a producer.

DAVID FARRIER: We did a Kickstarter early on, Dylan and I, and he came across the Kickstarter. I can’t speak to what he was thinking, but he saw it obviously, liked what he saw, and backed the Kickstarter at a level where we basically agreed, “Have whatever title you’re comfortable with and we’ll tell you whatever you want to know about the film as it’s going on.” He emailed, “Have fun guys, make a great documentary, and keep me informed how you’re going.” He watched some cuts and gave us great feedback.

BROWN: And at that point you were still investigating this competitive tickling league, rather than this trail of fraud.

FARRIER: Really early on we were just interested in this Jane O’Brien Media, which was very litigious and homophobic, and also seemed to be strangely bullying of the people they hired to do some of their tickling videos. I think Stephen was drawn to the story because of the aspects of online harassment and homophobia. Then, of course, for all of us, the story unfolded and got crazier and crazier from there.

BROWN: You mentioned some people refused to be interviewed. Did you get turned down a lot?

FARRIER: Yeah, a lot of people turned us down. They were dealing with this unusual situation where they had stumbled upon this tickling competition and a lot of them had taken part. Some of them had had good experiences and wanted to move on with their lives, and some had had terrible experiences and the last thing they wanted to do was talk about it again for fear it would get worse, or that I was potentially involved in this world as well. I’m just this strange man from New Zealand getting in touch with them saying, “I want to talk to you about this tickling experience you had.” There was a lot of suspicion and paranoia and that made it particularly difficult to get a hold of people.

BROWN: But you did run into people who were like, “It was a great experience.”

FARRIER: Absolutely. When you consider 10 or 15 people went to the shoots every month or something, a lot of them would get paid, get tickled, go home, and then never think about it again. Some of them, for reasons that often they couldn’t even really determine, became the target of this strange harassment campaign.

BROWN: Had you ever thought about making a documentary before this film?

REEVE: I hadn’t. [Or] it’s not that I hadn’t, but nothing ever caught my fancy and made me suddenly fancy myself as a documentary filmmaker. I usually work in television postproduction. I made some short films. It was always a form I was interested in, and I guess it was a story that turned up that seemed like the right opportunity to pursue.

FARRIER: I always wanted to make a documentary but I failed miserably until now. I tried to make a documentary about the Mongolian death worm. I went to Mongolia with my friend and we started filming, but the whole thing fell apart for a multitude of reasons. I’ve pitched other documentary ideas, and this is the first one that suddenly and very organically took off. I think it’s because the story was fascinating and resonated with people in different ways. It’s talking about online harassment and power and control, all these issues that are on a lot of people’s minds in the modern world. Also Dylan and I were sucked into this vortex because we were coming under legal threats for wanting to make the film. It was kind of unavoidable.

BROWN: How was the editing process?

FARRIER: It was edited by Simon Coldrick, who I’ve worked with in the past in television, and he’s done a few feature films more recently. He came on and was fantastic. It’s really good in the editing especially to have fresh perspective—you need to look at things with a fresh pair of eyes and see almost the perspective of an audience watching.

BROWN: Did he make you cut anything that you didn’t want to cut?

FARRIER: No, it was a pretty collaborative process throughout the whole thing. We knew where the story wanted to go, and he really smoothed things into shape. The main thing that we had to cut that was really frustrating was the introduction to Richard Ivey. He’s the tickling fetishist from Florida. I really loved his introduction—he was singing karaoke, but we didn’t have the rights to that particular karaoke song, so we had to cut the scene out. As far as what we had to cut, it was for very different reasons than what you might think.

REEVE: David was in the editing room with Simon and I was watching a cut at the end of the day, and things were cut in a way that I wouldn’t have thought of. I think that was really good as well, to have a different style. If I had spent all that time editing with them, I might have fought with them about some of those things, and I’m glad I didn’t.

BROWN: Did you watch other documentaries while you were making it?

FARRIER: Yeah. We’re all fans of documentaries, and we were all a bit obsessed with Serial and The Jinx and other longer form types of storytelling at the time. We took inspiration from the visual style of those shows, and the way you can take the viewer along on the same journey that we went on. The Imposter was another film—

REEVE: That has beautiful visuals.

FARRIER: Beautiful, wide shots for those views. [Our cinematographer] Dom [Fryer] used that as a visual style guide as well. Biggie & Tupac was a great form of inspiration because it was a documentary maker who was in the film himself, and it was interesting watching how he did that. We watched a lot of docs, and we brought a lot of different things from different films to this doc.

REEVE: There was no documentary that we could think of, and I’m still not sure of one, that really faced the same challenges as we did, in terms of how we were unavoidably enmeshed in the story and the type of story we were trying tell. All our inspirations had to come from lots of different places, whether it be The Imposter or The Jinx or even Supersize Me.

BROWN: What’s the strangest tickling utensil you came across?

REEVE: We got tickled by Richard Ivey. There were some instruments there that made sense for tickling, but the worst by far was a hairbrush that’s got the long straight frizzles and the little knobby that’s on the end. Across your feet, that’s the worst tickling you can imagine.

FARRIER: I found the electric toothbrush probably the strangest, because I never thought of the electric toothbrush being used for anything but teeth. Suddenly having it harassing a man’s nipple was unusual.

BROWN: Would you describe the film as humorous or funny?

REEVE: Certainly at parts.

FARRIER: I think it’s a real mixture. There’s humor and darkness in there, and I think one highlights the other. The film changes as well. It starts somewhere fairly funny—it’s light and it’s about a tickling competition. Then it takes you somewhere very different.

BROWN: What would you have done if some people had been successful in shutting down the film through legal means? Was there a point where you felt a moral obligation to let the world know about what was going on?

REEVE: In a sense, but I don’t think there was a time where we would have let that happen. We knew the constraints in which we could work and we had people who believed in what we were doing and fought for what we were doing. We just weren’t going to let it stop. There were times, perhaps, where things were more daunting than other times, but we figured it was the right way to go and we were really sure we were on the right path.It’s amazing how much curiosity will keep you going.

BROWN: During the Q&A after the film premiered at Sundance, you told the audience that one of them had probably been sent there to spy on the film. Was that the case at Sundance?

REEVE: I don’t know if it was at that screening or the one that after that, but Kevin, who’s featured in the film, was in the audience taking notes. [He] was noticed by the audience around him. That was obviously a surreal experience for those people—sitting in the audience and having this character from the screen next to them.

FARRIER: At another screening there were two gentlemen who looked a little out of place holding coffee cups in a very suspicious way. We figured they might be recording the film and we ended up getting the police to remove them. Surely enough, they were two private investigators from New York who had been hired by somebody to try to record the film. There’s been all sorts of fascinating things happening along the journey. With every audience, we have to assume that potentially someone from Jane O’Brien Media or hired by Jane O’Brien Media is recording things. I can only assume there’s someone taking notes in our live Q&A’s and I imagine that’s going back to the people behind Jane O’Brien Media.

BROWN: It’s strange that the private investigators would use a camera hidden in a coffee cup to try and record the film as you used that exact method in the film.

FARRIER: That was what we thought! That must have been a coincidence. These private investigators, they were the real deal. They looked like hardened New Yorkers. I thought they would have had a pretty covert way to do things but I guess they picked my method in the film, which was to shove a recording device in a coffee cup. The humor in that wasn’t lost on us.

BROWN: I can’t imagine being sent to investigate the film, watching it, and feeling comfortable reporting back afterwards.

FARRIER: Money. They probably got paid pretty well, and if you get paid to do something then you do it.

TICKLED COMES OUT TODAY, JUNE 17.