Pink Moon is On Its Way

Chaser, a provocative short film by Sal Bardo, is stamped with an NSFW advisory, and with good reason. Over its 15-minute runtime, Zach (Max Rhyser)—a young, gay schoolteacher—breaks from the creeds set in by his conservative Jewish upbringing to explore the facets of his unorthodox sexuality. This exploration leads him to a “breeding ground” barebacking party in New York City. “No condoms, it’s rude,” he’s told at the door. Soon enough, the kind, enthusiastic schoolteacher is unmasked as his paradox: a sexual deviant, a “bug chaser,” a man who seeks out HIV infection through unprotected anonymous sex. As titillating as it is distressing, the film is an engrossing take on the complexities of both inter- and intrapersonal intimacy within the LGBT community.

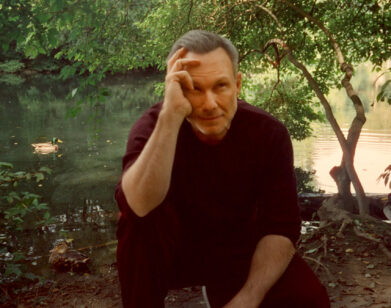

Writer/director/producer Bardo is a studied musician, a professional actor for both film and stage, and now a modestly decorated filmmaker on the rise. He notes Gus Van Sant, Mike Nichols, Jean-Luc Godard, and Gregg Araki as inspirations. Though an auteur with only three short narratives to his name—Requited (2010), Sam (2011), Chaser (2012)—topical, LGBT-themed terrain has become a staple of sorts within his work. Whereas many comparable contemporary titles find solace in the gimmick of “gay,” Bardo explores subcultures within the niche and sexuality’s varying effects on identity and community. It is a resolutely humanistic approach that leaves an impression not easily forgotten.

Bardo says that his fourth short is his best to date. Pink Moon is a companion piece to Bardo’s feature-length screenplay, his first. Depicting an imaginary homonormative society in which heterosexuals are persecuted and reproductive rights are inhibited, Pink Moon is a love story of two teens who are forced to hide an unintended pregnancy.

With the project’s Kickstarter campaign underway and rounding its final two weeks, we spoke with Bardo about maneuvering the limitations of an indie budget, finding his niche in the LGBT market, and ensuring that his “first pancake” came out looking perfect.

BENJAMIN LINDSAY: You studied music at NYU, you’ve acted professionally, and now you’re making acclaimed short films. Do you feel you excel most at any one of those crafts?

SAL BARDO: Yeah, well, I definitely feel like I’m doing what I’m supposed to be doing now. It took me a while to figure out. As an actor, you really don’t have much control over the parts you get or the quality of the material, so I made my first short film [Requited] primarily as a vehicle for myself as an actor. Then, after I wrote it, I decided I didn’t want anyone else to direct it, so I directed it myself and I sort of downgraded myself to a little cameo part. I’ve had much more success as a filmmaker than I ever did as an actor or a musician, so I think that that sort of speaks for itself.

LINDSAY: How do you feel your background in the other two affects your approach to filmmaking?

BARDO: Because of my acting background, I think I work well with actors; I think I direct actors well and I think that’s sort of where my strength is. I didn’t go to film school, so I typically surround myself with people who know what they’re doing in terms of the technical aspects of filmmaking. I’m sort of learning as I go and finding my voice, but on the other hand, because of that, I haven’t really had a lot of experience to experiment and make mistakes, so I feel a bit of an added pressure to make sure everything is done right. I had a filmmaker mentor of mine tell me really early on that—I’m kind of a perfectionist, and so [for my first film] I wanted everything to be perfect. And he says, “Your first pancake is never perfect.” I wanna make sure I make a film that doesn’t look like a first pancake.

LINDSAY: Now, with the success of that “first pancake,” Requited, I feel like it’s definitely the most commercial film that you’ve made. Did you use that success to explore darker themes in your second and third projects?

BARDO: I didn’t really intend on making any other films except for that first one, to be honest. I think for me, I just want to make movies about stuff that interests me. I have a friend who laughs because he says, “Oh, all your films are LGBT-related, and that’s not really all you’re about—you’re about so many other things.” And that’s true, but it also seems to be where I’m finding my voice in that niche right now. Ultimately, I want to expand and go beyond that, but these are just issues that, you know, I see them on the news, and that’s what gets me riled up and passionate.

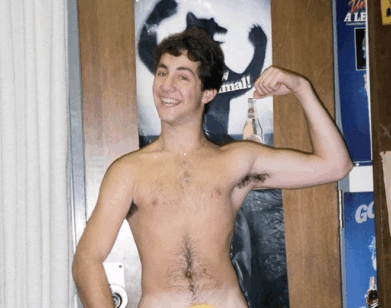

LINDSAY: You had mentioned earlier that as an actor yourself, you have a really good rapport with your actors on set. How did your working relationship begin with Max Rhyser, star of Requited and Chaser, come about?

BARDO: He was in Requited, and I typically become friends with the actors I work with, so we hung out a couple times, and we were talking about how we wanted to do something together again, and we started talking about “bug chasing,” which is something that we had both been intrigued by and sort of encountered in our personal lives, and we thought that it would be an interesting movie to make. We also have to be careful because ultimately, the film isn’t about bug chasing. I mean, that’s where the title comes from, but in the end, it’s really just about the one character who explores the barebacking scene.

LINDSAY: What is it about that bug chasing/barebacking subculture that intrigued you?

BARDO: Society still has so many hang-ups about sex and sexuality, and I wanted to explore that a bit. What makes us attracted to the taboo and how has the gay community sort of fetishized barebacking? I just wanted to understand the motivations behind these young men who I was meeting who didn’t seem to think that contracting HIV was a big deal. I’m too young to have experienced the peak of the AIDS crisis, personally. I remember growing up and seeing it on TV and in the movies, and, you know, we were taught in health class that having sex would kill you and being gay would kill you, and that’s not really the case anymore, and it’s a wonderful thing, but we have an entire generation of activists to thank for that. Many of them are gone now. I was a little kid then, but it makes me feel old to meet these younger guys who don’t understand that importance of ACT UP and amfAR and Madonna, you know?

LINDSAY: You definitely have a point. I feel like 30 years later and, at least with gay guys my age, conversation surrounding AIDS seems to downplay the fact that it was a plague.

BARDO: Maybe it’s an age thing or maybe it’s just willful ignorance. After having made [Chaser], my views of have definitely evolved—I feel like I have a better grasp on what the different motivations are, and it’s not just about self-destruction and it’s not just a negative thing. It’s a sexual expression, and it’s a reaction to being oppressed for decades. I think after generations of that, we’ve sort of come bursting out of the closet sexually, and not everyone in the community is very accepting of that.

LINDSAY: To touch on your new film, Pink Moon, the premise of heterosexuality being persecuted is a not-so-subtle nod to the way homosexuality is traditionally flagged in today’s society. Why is this story an important one?

BARDO: I guess after I made Sam, which was similarly about bullying and gender identity, I sort of wanted to continue going down that path; I hadn’t fully addressed it, I felt, creatively. It’s a premise that has been tossed around for the past 50 years. There was a short story called “The Crooked Man” that was published in Playboy in the 1950s, and that took place in a world where heterosexuals were persecuted, so it’s not a new concept, I just think it happens to be exceptionally relevant right now. Right now, there’s an all-out assault on reproductive rights in this country, and the same thing is happening with LGBT rights, as you had mentioned earlier: we’re making these huge strides with marriage equality, but whenever there’s progress, there’s pushback. Both of those issues are about personal freedom, and they’re fundamentally connected. So when I was writing the feature-length script for Pink Moon, I started thinking about how a homonormative society might affect women’s rights, not in a sexist way, but in terms of procreation. For example, accidental pregnancies would be a much rarer thing if everyone was gay, and it would only affect a small minority, so that reality would be very similar to, say, 1960s America. For me, it was a really relevant way to explore both of those issues at the same time, and it added another layer to the concept of a homonormative world.

LINDSAY: The feature-length screenplay for Pink Moon was a finalist in the CineStory Screenwriting Competition and Final Draft’s Big Break Screenwriting Contest. How are you planning on adapting that script into a short film?

BARDO: It’s funny, I really struggled for a long time. I had no interest in making another short film. I made three, and I was ready to make a feature film, but financially, I wasn’t ready. I didn’t know how to raise that kind of money, and, again, I’ve only been making films for three or four years, so I don’t have the access or the notoriety to really be able to get the script to the people who could finance it. And then it took me a really long time to figure out how to distill 91 pages into 15 minutes. That was a big struggle for me, and then I decided to just scrap it and write something completely new. So it takes place in the same world, and it’s sort of the pre-history to the feature, if that makes sense.

LINDSAY: Okay.

BARDO: So the feature opens with the main character from the short, and then for the rest of the film, there are different characters that become the main characters. So I use that character from the first scene and decided to tell his story. And in the process of doing that, the reproductive rights angle actually became more pronounced in the short. I think what’s ultimately going to happen is I’m going to go back and retool the feature, which I’m really proud of—I could shoot that script tomorrow if I had the money—but I’ve sort of fallen in love with the short concept that I’ve made, so I’ll probably go back and tweak the feature to make it a little more similar to the short. They don’t tell the same story, but they’re definitely related.

LINDSAY: You’re entering the final two weeks of Pink Moon‘s Kickstarter campaign, and you’re a little under halfway your $10,000 goal. Do you think in this day and age crowdsourcing is a necessary tool for independent filmmakers?

BARDO: Yeah, absolutely. Recently, I was talking to a director friend of mine who’s sort of a queer film pioneer and he was talking about how things are so different, but for me, I don’t know what it’s like to make a movie without being able to reach out to people directly. For me, this is the norm and this is the way it is. I guess 20 years ago, there was a lot more money floating around in terms of financing from studios and producers and it’s a lot harder to get that now. But on the flipside, we have the Internet; we have this amazing platform to reach people that we never would be able to reach prior to this. People are sort of lamenting the death of cinema and film and financing, but for me, I feel that the possibilities are endless.

LINDSAY: It’s not so much a death as it is a transition.

BARDO: Yeah, it’s a transformation. It goes back to the thing about AIDS we were talking about: each generation has a different perspective and a different reality. One generation may think that they have it better or worse, but you don’t really know, right? You only know your own reality. For me, I just wanna tell good stories, and it’s exciting to have people who I know and then people who I don’t know both contributing to help me bring the story to life.

FOR MORE INFORMATION ON SAL BARDO, VISIT HIS WEBSITE. FOR MORE ON PINK MOON‘S CAMPAIGN, CLICK HERE.