How Rachel Lears Filmed the Moment Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez Changed Politics Forever

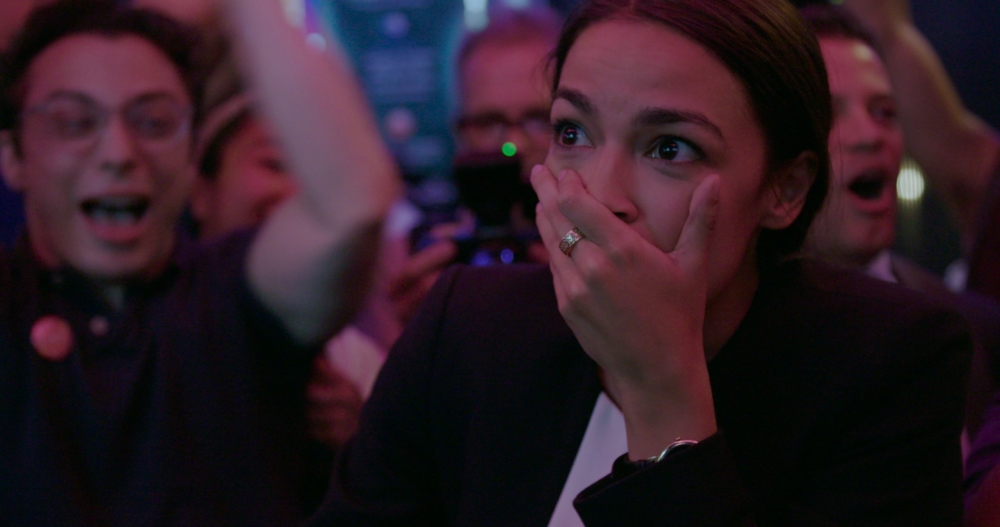

The night of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s historic win, from Knock Down the House.

Since her surprise midterm upset of a Democratic incumbent in New York’s 14th congressional district, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez has become an emblem of hope and change — and a testament to the power of biting Twitter retorts (for most, at least). But before the 29-year-old’s surge to the top of the national conversation, the congresswoman was a bartender with scant political experience, a point she proudly espouses still. During the summer of 2018, as Ocasio-Cortez plunged headfirst into the race — despite polling that showed her to be 30 points behind incumbent Joe Crowley — filmmaker Rachel Lears began to follow along, documenting the highs and lows of the underdog campaign. That summer, Lears decided to track three additional female candidates, each running progressive primary challenges: Cori Bush, Amy Vilela, and Paula Jean Swearengin. The result is her documentary Knock Down the House, an intimate look at four women determined to change the system, each fueled by personal stories of working-class struggle. AOC’s bid was grounded, in part, by her father’s passing, forcing her to work double-shifts at the bar in order to save her family’s home in the Bronx. Vilela’s congressional run in Nevada was a race that focused on universal healthcare, having lost her daughter to a preventable health condition amidst an insurance gaffe. Bush was a nurse in her native Missouri before being swept up in the Ferguson protests. In West Virgina, Swearengin sought to unseat Senator Joe Manchin, a coal executive, after seeing her friends and family die of disease caused by the environmental effects of coal mining in the region.

Though Ocasio-Cortez was the only woman to win her primary, it’s the collective power of their stories that propels the film, and serves as a testament not only to the persistent determination of these individuals, but to the will of the human spirit. Interview sat down with Lears to discuss her own journey alongside the candidate, a grueling two-year “emotional roller coaster” during which she pulled double-duty to raise her baby son. With a documentarian’s sense of candid empathy, Lears spoke of the history-making night of AOC’s win, overcoming self-doubt, and striking the iron while it’s hot.

———

SARAH NECHAMKIN: What was it that you saw in Ocasio-Cortez, long before the media began its obsession with her? Was it the same for the other three women you followed?

RACHEL LEARS: It was their very personal reasons for doing what they were doing. It’s not easy to challenge an established politician, especially if you’re a regular person, and especially if you’re not taking corporate funds. Where were they getting that strength and courage? Each of them had high stakes personal experiences that they were drawing on in their campaigns. We didn’t know what was going to happen — it easily could have happened that they all lost, so we needed that personal element in there to make it worth doing this project in the first place.

NECHAMKIN: How personal did it become for you in the process of filming?

LEARS: There was a lot of negotiation with each one of them: What do you feel safe letting me film? What are you comfortable with? If this doesn’t work, what’s the alternative? There are a lot of conversations to build trust that happened before the camera actually turned on. Then going through each of their election nights was just such an emotional roller coaster. Nobody knew what was going to happen. There were no polls or anything. June [of 2018] was particularly intense. We had the Nevada primary and the New York primary just two weeks apart. Going through that moment of devastating grief that Amy experiences upon losing her election, and then two weeks later, having this incredible unexpected victory with Alexandria — that was a moment where I knew, we’d gotten a range of human drama that is really wide for a documentary, not to mention a historic moment.

NECHAMKIN: What it was like filming during the night of Ocasio-Cortez’s victory?

LEARS: An out-of-body experience, just going through that whole process with her. She refused to look at the returns for half an hour. I learned that she was ahead at the same moment she did.

NECHAMKIN: The camera was shaking because you were running to catch up to her.

LEARS: Yeah, I was running after her, and then we had our second camera person in the bar already. I pushed my way in right behind her, and we got the whole thing with two angles, which is really great. It was like a well-oiled machine. We knew something was going to happen, so we wanted to make sure we’d be there.

NECHAMKIN: There were so many moments of transparency — seeing Ocasio-Cortez sitting in her apartment with her boyfriend having these moments of self-doubt, practicing affirmations.

LEARS: That was a huge part, I think, of why she agreed to do the film in the first place. All four of them saw the value in that transparency. They’re campaigning on the idea of transparency and authenticity, anyway. It’s a natural step to say, “Sure, let’s have a document of this process.”

NECHAMKIN: Did you personally struggle with self-doubt while filming?

LEARS: My child was eight months old when we started. He just turned three. I didn’t know it was possible to make a documentary so grueling. In the month of June, I was shooting every single day with 15 to 20 pounds of camera equipment on my shoulder every single day. We’ve been working non-stop, for I don’t know how long now, to get this film out. How do you do that if you’re not working with people that are giving motivational speeches all the time, to themselves, and others, and just really going through that process of “Where do I get my strength from to keep going?” You’ve got to reconnect with that every single day when you’re doing something as grueling as campaigning. It’s the same thing with documentary filmmaking.

NECHAMKIN: It’s powerful to see women in the spotlight openly saying they have self-doubt and imposter syndrome, rather than shielding it in power suits.

LEARS: I realized at a certain point that it was part of a trend. This new wave of female candidates were doing things that female politicians had been advised not to do in the past. Things like, “Don’t talk about your kids. Don’t talk about your feelings. Don’t talk about this, that or the other thing, your hardships, or your real life.” This all turned all of that on its head. All of these candidates were saying, “You know what? I am strong because I’ve been through this stuff.”

NECHAMKIN: Did the thought ever cross your mind that any of these women, particularly Ocasio-Cortez, would attain the sort of celebrity status that she now has? Does that just blow your mind?

LEARS: I knew it was possible, and I hoped that at least one of them would win. Alexandria was getting a fair amount of press. She was building a social media following in the last few weeks before her primary. But I definitely did not foresee the media superstorm that would arise around her afterwards. She’s obviously a lightning rod for some of the divisions that exist in our society. She’s struck a chord. She really is who she says she is. You can see it in the film. She is willing to be powerful and vulnerable at the same time and really talk about the way her personal experience connects to political realities that lots of people face. I think the fact that that’s so popular shows that people are hungry for that.

NECHAMKIN: Nancy Pelosi said a glass of water could’ve won in her district.

LEARS: But a glass of water couldn’t have won the primary. It’s disrespectful and short-sighted. There are conversations that are happening within the Democratic Party about what the soul of the party can be and should be. There’s a lot of opposition among established politicians to the very idea of primaries. All of these candidates faced a lot of flack just for challenging politicians who hadn’t been challenged before. Why shouldn’t the people be able to choose who their representatives are?

NECHAMKIN: Was there anything in particular that surprised you about the candidates as you were filming?

LEARS: I was just continually surprised by the fact that each of these candidates was able to keep going with everything. It’s a lot of pressure. There’s so much you have to do. You’ve got to knock on those doors yourself. You’ve got to do all the press appearances. You’ve got to handle the social media hate. You’ve just got to bring it every single day. I was just very impressed with how Alexandria did that, and the others as well. Every time they met someone, they would just make that person feel like they were important, and it meant something to them. It wasn’t fake. They really cared about connecting with each one of those people.

NECHAMKIN: Have you followed up with them since?

LEARS: I’ve stayed in touch with all the women in the film, and I’ve met a few others like Ilhan Omar. They’re awesome. I really hope the film can help support the conversations that are already happening and start some new ones. I’m optimistic because I have to be. But I’m not optimistic in an unrealistic sense, and that’s why I think it’s very important to have the losses in the film. We never considered cutting them out. Of course, the industry people started talking to us in July about, “Why don’t you just make it about Alexandria?” And I was like, “Just wait until you meet the others. It’s worth it.”

NECHAMKIN: After we see Vilela lose her campaign, Alexandria calls her up and says, “One hundred of us run. One of us wins, and it’s still worth it.”

LEARS: It’s not just worth it because one wins. It’s worth it because each of them changed the conversation in the process.