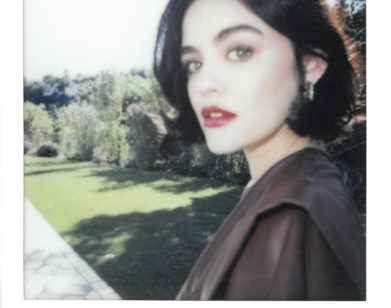

Oscar Isaac

OSCAR ISAAC IN NEW YORK, OCTOBER 2013. JACKET: (VINTAGE) SCHOTT NYC. T-SHIRT: CALVIN KLEIN UNDERWEAR. RINGS: DAVID YURMAN AND EDDIE BORGO. STYLING: ANDREAS KOKKINO. GROOMING: VALERY GHERMAN FOR TOM FORD/ART DEPARTMENTVAL.

I got an acoustic and started taking lessons. i wanted to be able to shred like yngwie Malmsteen. Oscaar IsaaC

The Coen brothers’ new film, Inside Llewyn Davis, dives headlong into the nascent days of the Greenwich Village folk-revival scene of the early 1960s. Loosely based on singer Dave Van Ronk’s posthumously published 2005 memoir, The Mayor of MacDougal Street, it’s less a star-studded time-travelogue than a starkly reimagined black-and-white tone poem to the milieu and the music of the period. The action takes place over a period of a week in 1961—the year that Bob Dylan would arrive and change everything—and is orchestrated around a number of full-bodied live renderings of old chestnuts from the folkie songbook overseen by the movie’s musical director, T Bone Burnett. Of course, in order to execute a film like this, one needs a delicate mix of actors, some semblance of whom can actually play music and sing, and musicians, a handful of whom can at least nominally act (as something other than themselves). Llewyn Davis has both in abundance, with a cast that boasts Carey Mulligan, John Goodman, Adam Driver, Garrett Hedlund, and two-way man Justin Timberlake, and a soundtrack that includes a number of musicians at the fore of the current revival of the old-music revival, such as Mulligan’s husband, Marcus Mumford of the band Mumford & Sons, who worked with Burnett on the music, and Chris Thile of the Punch Brothers.

At the center of it all is Oscar Isaac, who stars as the film’s titular Davis, a struggling (and entirely fictionalized) folk singer who, in the waning pre-Dylan days, is languishing in the then-obscurity of clubs like the Gaslight as he attempts to get his ever-complicated life in order following the suicide of his songwriting partner. But while Davis’s life most determinedly isn’t Van Ronk’s, his repertoire is, filled with traditional ballads like “The Death of Queen Jane” and “Fare Thee Well (Dink’s Song),” as well as other old nuggets that Van Ronk, a jazz-trained vocalist and guitar player, frequently dragged out and remade, like Len Chandler and Robert Kaufman’s “Green, Green Rocky Road.”

In September, the Coens and Burnett arranged a one-off concert, “Another Day, Another Time: Celebrating the Music of Inside Llewyn Davis,” which was designed as a benefit for the National Recording Preservation Foundation and filmed for a Showtime special set to air in December. In addition to performances by those involved with the film, including Isaac, Mulligan, Mumford, and Thile (the Punch Brothers served as the house band), the show also featured contributions from a number of other high-profile folk enthusiasts, including Joan Baez, Bob Neuwirth, Elvis Costello, Patti Smith, Jack White, Gillian Welch, and Dave Rawlings, as well as nu-folk torchbearers like the Milk Carton Kids, Lake Street Dive, and Rhiannon Giddens of Carolina Chocolate Drops. Conor Oberst also played that night, which is when he met Isaac, 33, and the two quickly bonded over their mutual folky fan-boydom. They recently reconnected over the phone to discuss bringing Llewyn Davis—and an entire era of music—to life.

CONOR OBERST: I know I told you this when we met, but I tried out for your role in Inside Llewyn Davis—and thank god for everyone that I didn’t get it. But they auditioned a lot of musicians and actors for this part, to the point where I heard the Coen brothers and T Bone Burnett say that they had more or less given up on the idea of finding someone. And then you appeared. When you first heard about the role of Llewyn Davis, did you feel like it was a role that you were uniquely prepared for? Did you feel like there was some hand of destiny involved in you getting it? Or did you think about it like any other role that would come up?

OSCAR ISAAC: I definitely felt the hand of destiny massaging me and pushing me toward it. This thing was definitely in my sights, for sure.

OBERST: I think it’s hard to make a good movie based around a musician—most of them are actually pretty terrible. But Llewyn Davis really reminded me of a lot of friends I’ve known and people I’ve met along the way who were very talented and, by all standards, should have received the opportunity to have their music heard by a wider audience, but for whatever reason, they just never did. Did you draw on anyone you knew of, or even any of your own experiences as a musician and an actor, in the way you approached this character?

ISAAC: Yeah, absolutely. I mean, there are tons of people I know who have gone through what you’re describing. I think that when you decide to dedicate yourself to creative endeavors and surround yourself with people who are creative, you very quickly learn how hard it is to survive doing those kinds of things, not to mention make a living at them. Early on—certainly in acting—you really have to take whatever you can get. So I understand well how difficult it can be to be in this position where people are just not hearing what you’re trying to say or are saying. I recognize that, and I know that the Coen brothers and T Bone do as well—this sense that, obviously, talent and hard work are involved in getting your voice heard, but that luck also plays a huge role in people getting the opportunity to do the kinds of things that we do, and in being able to continue to do them.

OBERST: T Bone Burnett is a far-out guy. I love him—he’s super-trippy. What was it like to work with him on this film?

ISAAC: He’s a musical Mr. Miyagi. He just kind of floats around and drops wisdom, and you have to be quick enough to pick it up. He would be there on set, and whatever I was playing, he’d be listening and timing it. The musical scenes in the film were done live, so we’d probably do a total of six or seven takes of each of the songs, but in different setups—we’d do a close-up and a medium and then one with two cameras, and one or two takes of each. I think, for the most part, they would just use one take, but since I was able to stay in tempo, they had the ability to cut in between different takes.

OBERST: The way those sequences were handled just felt very real.

ISAAC: And that was super-important—I think that’s why the performances had to be live. When you play it back, you can see if the hands aren’t really doing the right thing, and then the whole magic falls apart. If it had been one of my favorite singers playing this part—if it had been, like, a Thom Yorke—then I’d want to hear their actual voice in the scene. But basically, you would do a song once, and T Bone might come over and say something like, “That one started to feel a little bit forced,” or “Relax your hand a little bit,” and that was it, man. What was also interesting for me about playing those songs in those scenes was that, obviously, I needed to play this character, Llewyn Davis, who has a very particular voice and is playing a very particular style of music. But doing that was also an opportunity for me, Oscar, to be the musician that I’d always wanted to be as a kid—and to actually sing with that kind of honest voice that I’d always wanted to sing with. So I thought about that, too, in doing those scenes.

OBERST: You played in some pretty fully functioning bands growing up in Miami, right?

ISAAC: I don’t know if they were all functioning, but I did play in a bunch of bands. I was sort of a musical whore, so I played in industrial bands, hardcore bands, punk—ska bands—all sorts of bands.

OBERST: Did you play guitar in those bands?

ISAAC: I played guitar and bass. I didn’t do much vocals, although I did have one band where I was the lead singer. But that was when I was in college.

OBERST: When did you start playing music?

ISAAC: Probably when I was around 12 years old. My dad always played a lot of music, so I heard him playing all the time, and then I decided that I wanted to learn to play guitar, so I got an acoustic and started taking lessons. I wanted to be able to shred like Yngwie Malmsteen. [both laugh]

OBERST: I’m sure you can shred.

ISAAC: Not really. I stopped taking lessons after about six months.

OBERST: When did you start to think about acting?

ISAAC: I was acting at the same time I was playing music. But by the time I got to college, the band I was in at the time was playing less, and I’d started doing more theater down in Miami. Then I got an audition at Juilliard for the acting program and I got in. So that’s when I quit the band and decided just to focus on getting better as an actor.

OBERST: Was it a tough decision for you to put music to the side in favor of acting? Or was the arrow already kind of pointing in that direction?

ISAAC: You know, at that time, I was in this punk-ska band, which was good—it was a lot of fun. At the same time, though, I didn’t feel like I was necessarily contributing anything to the medium, if you know what I mean. We were playing shows, and I was writing songs, and I was feeling good about it. We were a good band. But I didn’t necessarily feel like I was pushing any boundaries in what we were doing—I just felt like I was kind of ultimately exploiting the medium as opposed to really expressing myself, and with acting, I felt that there was maybe a little bit more room to experiment at that moment in my life. But I did continue to write music and play around with it, trying to figure out what my voice was within that.

OBERST: Obviously, you sing and perform on the soundtrack to Llewyn Davis, but would you ever want to make a record of your own? And if so, do you think it would exist in a similar world of music to the kind that you’re playing in this movie? Or would it be a completely different thing musically?

ISAAC: What ended up in the movie is really a mixture of me and Llewyn. It’s Llewyn’s voice, and all of his circumstances, with everything that’s happening to him, and his introverted nature—I’m not as introverted as a singer as Llewyn is, but my actual voice creeps in there as well. You know, I have been playing acoustic music for a very long time, and it’s something that I am very comfortable doing, so if I made a record, it would probably be a mixture of that and some other things that I’m interested in. But when you get into a certain kind of music as deeply as we did for Llewyn Davis—even though it was for this movie—it stays with you and resonates.

OBERST: Were you a big fan of that ’60s folk era of music in general? Or was it something that you really had to discover and learn about for this film?

ISAAC: Well, I’ve always liked acoustic blues. I liked Bob Dylan a lot. But I was really more familiar with certain parts of it than others.

OBERST: I know. Even though I like some of that stuff, there’s a lot of music from that era that I’m also not familiar with. Some of it has stood the test of time, and some of it has vanished a little bit.

ISAAC: Because it was so specific to its time and place. But a lot of the songs of that era that have had such staying power have done so because they’re just so direct. It’s like they’re recordings of a kind of truth.

OBERST: What was it like to work with the Coen brothers? Was it kind of a two-headed-hydra vibe? Do they do good cop, bad cop? What was it like?

ISAAC: They’ve each definitely got their own distinct personalities. I do always imagine them with, you know, berets on, like beatniks in a coffee shop. But they’re really mellow—the set on this film was an incredibly relaxed place. They don’t really seem to check in with each other about stuff like who’s going to come up to me and say something, or if they agree. I think the assumption going in was that we were all on the same page about what we were doing, and it was rare that there were any disagreements even between the three of us—or the four of us, with T Bone in the mix as well. All of us did tend to be on the same page, and there would just be slight adjustments where whoever felt the strongest about something won, you know? I mean, I grew up watching their movies, so I kind of got their tone right away, and was able to adjust really easily if there was something that was a little off here or there.

OBERST: We both played at that Town Hall show in New York in September, where everyone performed songs from the film as well as other folk songs. What was that experience like for you? I mean, you were up there with some pretty heavy hitters, like Elvis Costello and Joan Baez and Jack White, but you brought the house down. How did you feel about performing on the same stage as those people? Was it terrifying?

ISAAC: Totally.

OBERST: Was it more terrifying than—

ISAAC: Yes. [both laugh]

OBERST: Well, did you find it more or less terrifying having to do something like that in a musical setting, as opposed to when you’re doing a scene with an actor who is a heavy hitter, like John Goodman or Viggo Mortensen? Is the terror and nervousness that you feel in a musical setting better or worse?

ISAAC: Much worse. Especially since we were filming that show for a Showtime special, and I had to follow Rhiannon Giddens, who was incredible. But you only have one shot to get it right in that kind of setting, and you can very easily fuck up and drown out there, so that was scary to do. I saw some pictures of myself from that night and my eyes look really kind of slanty—I almost look strangely calm. But then I saw this thing on a National Geographic show about these sharks that release a chemical—I believe it’s when they get disturbed—that stops them from freaking out. They go into a kind of trance, and I think I had a little bit of that. Something like that might have happened that night to stop me from freaking out and biting people’s heads off.

OBERST: Well, I think you’ve got a bright future ahead of you, kid.

ISAAC: Thanks. I’ll see you in the pictures, kid.

CONOR OBERST IS A FOUNDING MEMBER OF THE BANDS BRIGHT EYES, CONOR OBERST AND THE MYSTIC VALLEY BAND, MONSTERS OF FOLK.