Oren Moverman’s LA Story

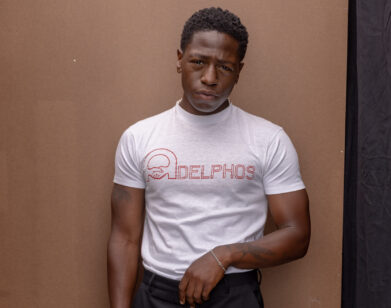

ABOVE: OREN MOVERMAN

One of the sheer pleasures of Rampart, the new film from director Oren Moverman (The Messenger), is watching Woody Harrelson let loose in the role of a lifetime. As Dave Brown, a power-tripping cop hell-bent on destroying everything around him, Harrelson is a repressed ball of anger—all heavy breathing, tense muscles, and ready to explode. With wonderful, if small, supporting turns from a revolving door of actors—Ice Cube, Cynthia Nixon, Anne Heche, Sigourney Weaver, Ben Foster, Robin Wright—the film throws you into the kaleidoscopic descent of the main character, and you’ll be hard-pressed to pull away.

Interview spoke to Moverman about the city of Los Angeles as a character, why he thinks Rampart is a feminist film, and his connection to this very magazine.

CRAIG HUBERT: James Ellroy wrote the original script of Rampart, and you wrote the subsequent drafts. Ellroy is such an iconic writer, with such a specific voice.What about that initial draft stuck out to you, and what did you think you could improve or streamline?

OREN MOVERMAN: What stuck out to me were the characters, before anything. Ellroy’s such a great narrative writer, and sometimes it’s easy to forget that he’s very original in the creation of characters. There was a lot of potential for the characters to go in a lot of different ways, almost in the sense that in doesn’t matter what narrative you put around them, they’re going to go to interesting places. My job, and it was a job, in the beginning, was to go into Ellroy’s script, which was incredibly complicated and sophisticated and really, at certain points, hard to penetrate. He really went far in how complex the script was. In a way, I was brought in to make it a little simpler. I obviously approached it with a lot of respect and reverence for Mr. Ellroy. What I tried to do is not so much rewrite him but get in his head.

HUBERT: A big part of the tone is the atmosphere of Los Angeles. How important was it to you to shoot there—to have the landmarks, the sunlight, and the palm trees?

MOVERMAN: All that was tremendously important—as important as the characters. We felt we were really being challenged to make a James Ellroy movie that’s different from all other James Ellroy movies. Los Angeles was the key to it—there is no way to shoot this movie anywhere else. Luckily, we had the financiers who agreed with us. As you know, most of the time people are thinking they need to shoot where they can get the biggest tax break. But the landmarks—the downtown area, Tommy’s Burgers, Pacific Dining Car—are integral to the story. As someone who doesn’t live in Los Angeles, for me, going in, it’s like a discovery. These places are fascinating as objects, an aesthetic specific to Los Angeles. It was either we shoot in L.A. and exploit the hell out of it, or not do it at all.

HUBERT: I read recently that you described the film as “interior.” One of the things I noticed is that film doesn’t adhere to the normal beats of a police procedural, instead slowly accumulating character details. The plot means very little in the film.

MOVERMAN: Absolutely. I think of this movie as a forensic investigation of a character, of a state of mind. It’s not really about what happened. The film becomes increasingly suggestive, to the point where Dave Brown is putting together his idea of what is going on. It’s so disjointed by the time he comes to any kind of conclusion that he’s so out of it and far down his demise. It can’t really make sense. What happens is you create a lot of these narrative holes, and ultimately you’re interacting with the movie trying to figure it out and realizing there’s nothing to figure out, only a person to figure out. That person is very complex. You can’t get a full picture of a human being in a lifetime, let alone a movie, but you can definitely get deeper and deeper into understanding someone. What that does in terms of understanding yourself is the interesting point for me.

HUBERT: What draws you to complex, or mysterious, characters? I know you’ve worked on a few biopics of musicians—Kurt Cobain, Bob Dylan, and Brian Wilson—and although Dave Brown is not a cultural figure in the same way, they are all figures who are not easily understood.

MOVERMAN: That’s a good question. I think, if I had to psychoanalyze it—which I don’t, you’re forcing me to [laughs]—they’re all men, and all the projects you mentioned are about the mystery and the theater of masculinity. It could be on a creative side, like a musician, or it can be on the practical side, people who do their job in a world of men, like a cop or soldier. Men are fucked up, and fucked-up creatures are interesting to explore.

HUBERT: What you just said about men being fucked up is interesting, because Dave, in the film, is always surrounded by females. Rampart is almost a feminine movie, or a male film set in a feminine world.

MOVERMAN: That started with Ellroy. That’s one of the things he made a strong point of—that Dave moves in a world of women. I took it further—I added more women, I changed some of the male roles to females—and it was really important to me to make this world a growingly feminized world. That’s why I think this is a feminist movie. One of the things the movie is saying is that the old, patriarchal, society is coming to an end. It’s really women, and woman’s perspective, that is going to save us from people like Dave Brown. That’s a perspective I have in life, in general, and that’s one of the ideas the movie is trying to push. Dave is living out a fantasy of power and sexuality, and he has this weird family situation, but ultimately, he thinks he can separate the two worlds. That’s not going to end up in a happy ending.

HUBERT: Your previous film, The Messenger, dealt with a character in the army and this film deals with a character on the police force. What interests you about these suited-up institutions? Your films are not critiques of the institutions, per se.

MOVERMAN: These kinds of investigations of masculinity are made easier, in the sense, that if you take an institution that is so traditionally male dominated, and you take men who put on uniform and play a theatrical part in life, as men, then you’re already setting up a world where emotional elements will disrupt that. This was no plan, by the way. These things just sort of happened. They make sense now, when you look back at them. These are structures I feel like understand.

HUBERT: Thank so much, Oren. It was a pleasure.

MOVERMAN: Thanks. You know, by the way, I used to work for Interview Magazine.

HUBERT: Really?

MOVERMAN: The first place I started writing in English was for Interview. It was about a young actress named Anne Heche. She was “someone to watch.” [laughs]

RAMPART IS OUT IN THEATERS TODAY.