The Gift of Gore Vidal

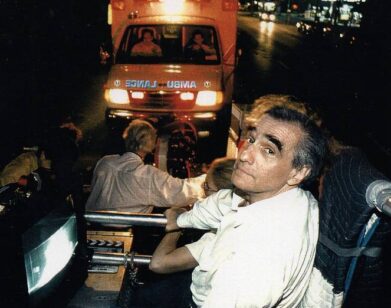

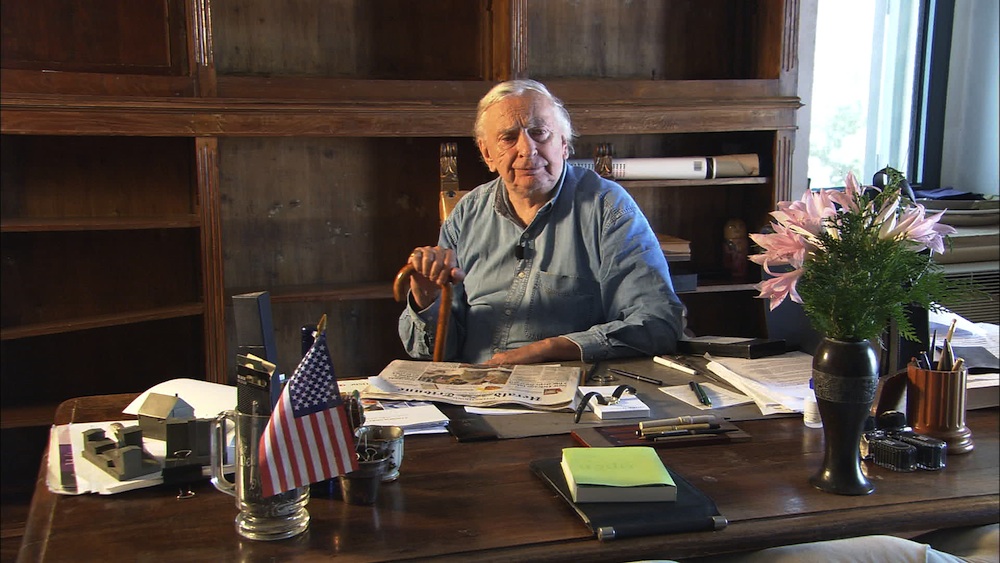

ABOVE: GORE VIDAL IN NICHOLAS WRATHALL’S GORE VIDAL: THE UNITED STATES OF AMNESIA. © 2013 AMNESIA LLC. A SUNDANCE SELECTS RELEASE.

As a young child, Nicholas D. Wrathall wanted to be the silver robot from the 1960s television sitcom Lost in Space. Instead, at age 21 the Australian-born Wrathall moved to New York, fell into the film industry, and became close friends with writer-director Burr Steers (Igby Goes Down, Charlie St. Cloud). Through Steers, Wrathall met one of his philosophical and political heroes, Gore Vidal. With Steers as the producer and Wrathall as the director, the trio began filming the documentary Gore Vidal: The United States of Amnesia.

The son of an urban planner and a psychologist, Wrathall was raised between Australia, Canada, and the U.S. While Wrathall says that his siblings are very creative, he describes his family as more analytical than artistic. “Growing up, critical thinking was important, and maybe that’s also what drove me to Gore,” he recalls. “I felt that Gore could be a real call to arms to people, and that’s what inspired me about his reading and his work. That was what I wanted to capture in the film,” he continues. “It wasn’t so much for him as it was his spirit for other people.”

Gore Vidal: The United States of Amnesia opens with Vidal giving us a tour of his graveyard plot and touches on his life as a child born into politics (his grandfather was the Senator Thomas Gore) and a bitingly clever witness to the failings of American democracy. As Vidal once told Interview in 1976, “The genius of the American ruling class is that it has been able to make the people think that they have had something to do with the electing of presidents for 200 years, when they’ve had absolutely nothing to say about the candidates or the policies or the way the country is run.”

The film, however, is not without its light moments. Charming and funny, Vidal joyfully recounts stories of target practice with JFK and Tennessee Williams (Williams was a crack shot; Kennedy was not), and the time Paul Newman came to his defense while holding a stolen beer backstage at a debate with Republican commentator William Buckley. Wrathall interviews many of Vidal’s family and friends including his late, one-time protégé Christopher Hitchens.

“The public intellectual side of Gore is what really fascinated me,” explains Wrathall. “That’s something that hopefully people get out of the film: the importance of critical thinking and being able to dissect the media and speak the truth to power.”

EMMA BROWN: I know you first met Gore through his nephew.

NICHOLAS D. WRATHALL: Yes, Burr Steers. I’ve known him for years, since he lived in New York in the ’90s. We’re pretty close. I know his whole family now and I’m actually godfather to his daughter. I’d heard stories about Gore many, many times and then had the opportunity to meet him at an Easter brunch—a very casual, friendly, family situation—and talk to him a lot about different things. I could see that he was open to the idea [of a film], so Burr and I approached him.

BROWN: I would be far too intimidated to have a conversation with Gore Vidal. He was obviously very witty, but also unforgiving in his wit.

WRATHALL: He was very intimidating, and I always felt like I was a little bit walking on eggshells. You didn’t really know if he was in a good mood; if he wasn’t, you could be in trouble. I tried to be as prepared as possible. He usually liked to control the agenda of what he liked to talk about—he wouldn’t talk so much about his personal life. I did follow him around a bit, too. I went to a bunch of events with him and trailed him for a while so he got used to me, so that helped a lot. The fact that I was a friend of Burr, maybe he wasn’t as suspicious as he might have been.

BROWN: Did he want to see the footage immediately after you filmed it?

WRATHALL: No. But at one point about halfway through the process, he did demand to know: “What’s going on with my film?” I gave him DVDs of a lot of material that we’d shot; we hadn’t started editing at that point, so it was pretty raw. I called a few weeks later and he said, “What are we doing next?” I didn’t really want to ask him what he did like or what he didn’t like. I didn’t want to get him involved in the editorial process because I thought that could be a really slippery slope.

BROWN: Obviously having a personal connection meant you got better access to Gore, but did it hinder you in any way? Was it harder to make a film about someone that you knew personally?

WRATHALL: I never really felt like I knew him well. He was pretty old when I met him, and he’d had a huge life and lots of friends and famous people that he knew. I was more someone that he allowed into his space. He treated me kindly and was generous with his time, and I did know him to a degree, but I didn’t know him the way a friend would. I felt like I was in the presence of greatness a lot of the time. Any subject you wanted to speak to him about, he was so knowledgeable in every way. I did feel a bit like [we had] a teacher-student involvement sometimes.

BROWN: Did he ask you about your life as well? Did he want to know about you?

WRATHALL: Yes, he did. The fact that I’d grown up in Australia was interesting to him. He knew a lot of the politicians on the left personally, and so he was always asking me, “What’s happening with this person? Bob Carr, he’s retired from state politics, is he going to go into federal politics?” and “What happened to this ex-Prime Minister?” I was really curious to why he knew so much about them and then it turned out that they were actually friends of his: they’d visited him, he’d mentored some of them in the ’70s. That was something we bonded over. I later interviewed one of them about him. It didn’t get in the final cut of the film because it seemed like most American audiences would be wondering, “Who is this Australian guy—who’s this guy with the funny accent?” [But] he had quite an interesting take on Gore.

BROWN: Are you generally interested in politics?

WRATHALL: Yeah, I am. That’s why I was excited to make the film. Everything I’d read of Gore’s, especially the essays—his critical writing after 9/11 attacking the Bush administration—I felt really in line with his way of thinking.

BROWN: You interview some of Gore’s family and friends in the film—his sister, Tim Robbins, Christopher Hitchens. Was there anyone you wanted to include who refused to participate?

WRATHALL: I asked Susan Sarandon and she was not available. There were a few people who weren’t available—they didn’t so much refuse. There were people that I wish I’d got. When I first met Gore and we started interviewing him, I was very focused on him and not on other people around him. In that time, Paul Newman, who was a friend of his, died. I really regretted never getting that interview because they were very close. I didn’t realize exactly how close they were until I spoke to Gore a lot about it.

BROWN: What was your initial idea for the film’s trajectory? Did you have one?

WRATHALL: My idea for the film, initially, was just to have Gore, and not to have anyone else in the film, which is why I started with interviewing him and researching the archival material. My focus was always about him and his critique of American history and politics—to focus on that and not to try and delve too deeply and try to dissect his novels. I feel like that’s a difficult thing to do on screen; that’s better done in print. I was always very interested in what his essays said and putting that on the screen, and the parallels he would draw between historical events right through the second half of the 20th century. As it turns out, he loved to speak about that. He was very motivated when I met him, and angry about the whole Bush era, so that directed a lot of the conversations. But I didn’t want to get stuck in that world too much; the film wouldn’t have had the timeless nature that it does now.

BROWN: Did you already have the title in mind when you started filming?

WRATHALL: No, I didn’t have the title at all. In fact I had some really lame title ideas in mind for quite a while that had the similar idea, but didn’t have the same strength or wit. I kept saying to myself, “We’re going to find the title in the editing process.” In the end, we did.

BROWN: You show some archival footage of Gore and William Buckley debating. Were you wary of asking him about people with whom he had these very public feuds like Truman Capote and Buckley? He must have been asked about them so many times over the course of his life.

WRATHALL: I did just bring it up, and often he would dismiss those questions because he didn’t want to speak about it. I would have a list of questions that I would just ask him again and again over a few months—or even years—to try and get some kind of response.

BROWN: How long did the film take to make?

WRATHALL: It took a long time. It was a very slow, organic start to the film. We didn’t have financing in place. We got some money from an investor, then he had financial difficulties and we lost that, so the film financially ground to a halt. The whole process was about seven years.

BROWN: Does the release feel anticlimactic?

WRATHALL: No, I’m actually still really excited about the release. My worry was always the timing; I thought the film would be out when Gore was alive and he’d be at the premiere and then, of course, he passed. The political situation was moving forward, and I kept thinking we had to get the film out now. But the more I see it in the festivals—the circuit we’ve been on—the more I realize he’s such a timeless man that it doesn’t really matter; people seem to always relate to his ideas. I think there’s still a big audience for the film.

BROWN: It seems like Gore got the best of everyone. Was there any point in your research where you felt, “Okay, Gore was outwitted this time”?

WRATHALL: Not really, to be honest. I wish I could say there was. Even with Buckley in those debates, there was so much back-and-forth, but when Buckley finally loses it and calls Gore a “queer,” Gore just smiles like that was his victory right there, to see this man lose it. There were stories about Gore being thrown out of the White House by Bobby Kennedy. But it never seemed like anyone got the upper hand; they just didn’t want to put up with his quips anymore. He never really backed down and he enjoyed a good fight. He was such a good debater and had such a sharp wit that very few people could stand toe-to-toe with him.

BROWN: I was surprised to hear his feelings about President Kennedy, that he thought JFK was such a terrible president.

WRATHALL: A lot of people are surprised by that—especially because you can see that Gore really likes the man and is a friend of his. [When Gore] cuts him down and says he doesn’t admire him as a president—that in fact, he was a bad president—Kennedy is held on such a pedestal by so many people on the left that there’s often a gasp in the cinema in that scene. I think it just shows that with Gore, he was very bipartisan in the way that he looked at the office of President. He felt like everyone that held it was pretty compromised in one way or another. I think Gore’s disappointment in Kennedy parallels his disappointment in the way the country has been going for a long time.

BROWN: Do you still feel in the film—do you ever find yourself relating things from the film to your life or vice versa?

WRATHALL: There have been a lot of strange [moments] where I would keep hearing things that he said in the film in my life. My father just passed away, and there’s a moment in the film when Gore is talking about [his partner] Howard [Austen] and that Howard said, “Oh, I’m 74, that’s when people die, isn’t it?” And my dad had been sick for the last six months and I kept thinking, “He’s going to make it to 75,” but in the back of my head, I kept hearing that line from the movie. So little things like that that I heard hundreds of times while editing the movie often pop into my head, and I don’t know if I’ll ever get completely out.

GORE VIDAL: THE UNITED STATES OF AMNESIA OPENS TODAY IN SELECT THEATERS IN NEW YORK CITY.