New Again: Martin Scorsese

Later this month, on its closing night, the Tribeca Film Festival will honor the 25th anniversary of Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas by screening a remastered version of the original film. After the screening, the creators and cast members, including Robert De Niro (who also co-founded the film festival), will reunite for a panel discussion, moderated by Jon Stewart, about the Academy Award-nominated classic.

Tickets for the event went on sale last week, so in honor of the occasion, we revisted an interview with Scorsese from our January 1987 issue. At the time, Paramount had just canceled the 43-year-old’s plans to direct The Last Temptation of Christ. Scorsese is as tortured, quirky, and brilliant as ever—and absolutely committed to his craft. To this day, Scorsese has 58 directing credits to his name—including feature films, shorts, television series, and documentaries—and given the recent announcement that he is likely to co-direct a version of Shakespeare’s Macbeth with Kenneth Branagh, he is well on his way toward his stated goal of 60. —Savannah O’Leary

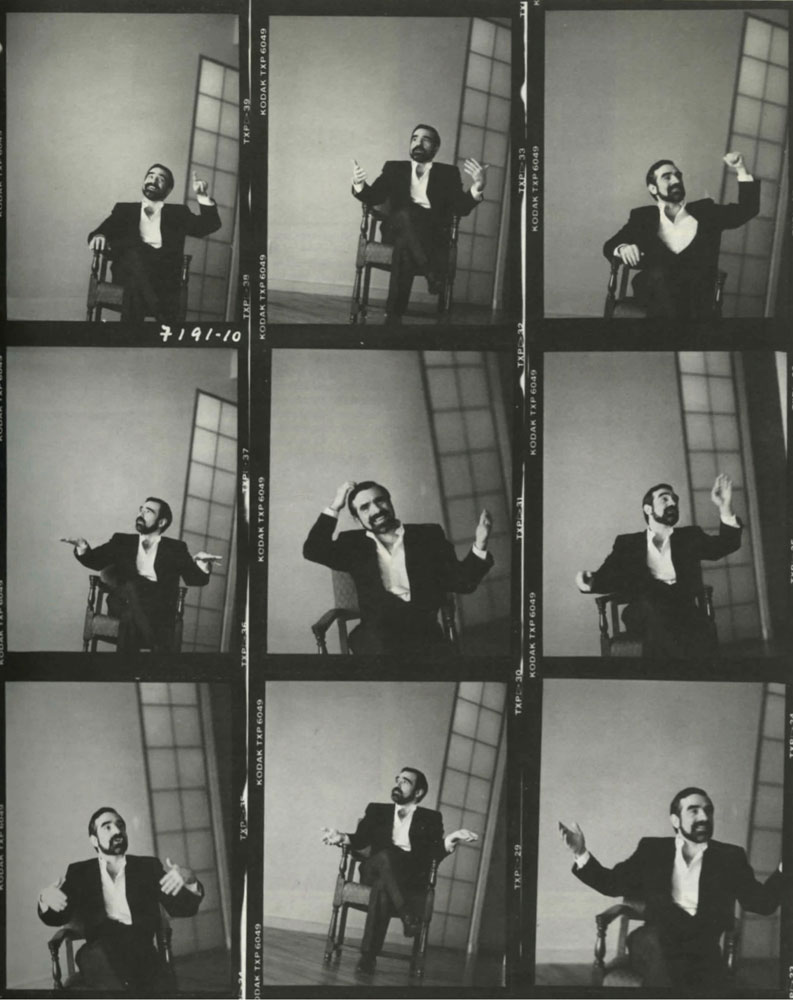

Martin Scorsese

by David Ansen

Martin Scorsese, a 43-year-old lapsed Catholic from New York’s Little Italy, worships celluloid images. Always has. When you drop in on the fast-talking director at his midtown Manhattan office or his TriBeCa loft, you can’t help but notice that Scorsese’s always got a TV running in the room with some old Hollywood movie silently rolling by. Today it’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, which gets him started on an assessment of director Tay Garnett’s career.

Short, bearded, and intense, Scorsese eats, sleeps, and breathes movies, and his obsession has made him one of a handful of American movie directors whose movies really matter. A Scorsese movie is always intransigently personal (Mean Streets), emotionally supercharged (Taxi Driver), stylistically daring (Raging Bull), and never safe or formulaic (King of Comedy; New York, New York; After Hours). He doesn’t swim in the mainstream, yet he now finds himself, with the success of The Color of Money, once again a hot Hollywood property. Disney, which made this Hustler sequel, recently signed him to a two-year contract to produce and direct movies. In various stages of development are a movie version of Nick Pileggi’s Mafioso book, Wise Guys, and a film about George Gershwin he’s working on with Paul Schrader. The project he’s most determined to make, however, is his oft-delayed adaption of Nikos Kazantzakis’ The Last Temptation of Christ, which was set to go almost four years ago with Aidan Quinn as Jesus and Harvey Keitel as Judas. At the last minute, Paramount pulled the plug. A true acolyte of cinema, Scorsese has been active in the campaign for film preservation and is one of the most outspoken critics of video “colorization” of old black-and-white movies. He is constantly adding to his own videotape collection of old films, which he studies and reviews as fervently as a medieval monk poring over sacred manuscripts.

DAVID ANSEN: All your movies, in their different ways, are incredibly personal. About King of Comedy, you once said that you were both Rupert Pupkin [the Robert De Niro character] and Jerry Langfold [the Jerry Lewis character]. Who are you in The Color of Money?

MARTIN SCORSESE: More like Eddie Felson [the Paul Newman character], but it’s a stretch. Would I be able to bounce back like he does at the age of 53, which is not that far away from me now? Would I have the guts of a Michael Powell [director of The Red Shoes] to keep coming with a project every day for the past 30 years, which is how long ago he last made a picture? Or will I allow them to kill my spirit, like they tried to do three years ago?

ANSEN: When The Last Temptation of Christ was canceled?

SCORSESE: Right. Now Temptation is a picture I would like to make. I’m not saying it’s going to be my greatest picture. It may not be a good movie at all. But I was supposed to make it, and I will make it. I will do it somehow. But what happened then was very strong, and since then I’ve been recuperating. And that’s what you see in these two movies, After Hour and Color of Money.

ANSEN: After Hours was a real regeneration.

SCORSESE: And Color of Money is a study, an aesthetic study—how you get Paul to look a certain way, how you get a ball to move a certain way and get a camera in place at the same time. It’s purely technique, the whole picture, and trying to make characters that are more courageous. It’s a terrible thing if you get to a certain age and feel you haven’t done anything.

ANSEN: You don’t feel that way, do you?

SCORSESE: I haven’t done enough. It’s ridiculous. I mean, I’ve made a few pictures, I have 60 movies to make, but the point is I don’t have the time now. I’ll really have to work until I’m 80 or something—if I live till then. I want to make 60, but I can’t do that. I’ll be lucky if I made another five or 10. What, I have to wait five or six years to shoot a picture because the script isn’t right? Why can’t I get in there and start moving away?

There’s a problem in the sense that the filmmaking school I came out of—not only NYU, but the style, which was nurtured on Kazan and Penn and Sam Fuller and Orson Welles and projected through Cassavetes and a touch of the New Wave—is very, very different from what you see UCLA grads doing. Directors come out of there and they’re professional directors. Me, I tend to be a personal filmmaker. And it’s very hard for me. I know that people who come out of UCLA tend to feel, “You give me a drama, I’ll do a drama. You give me a musical, I’ll do a musical. Because I’m a pro, and I’m proud of that.” I could do that, but I choose not to. You know what it is? It feels too much like work. I don’t like that. I never have. I’ve been thrown out of schools and fired from jobs. I don’t want to work. I can honestly say I haven’t done an honest day’s work in my life. They pay me for what I like to do, which is almost insane. And I always complain about it, too, the whole time—”I hate this, and I hate that”—but that’s what I do. My films really have to be a part of a whole body of work that says something to me. To me.

ANSEN: Would you ever go back to L.A. to live?

SCORSESE: No, no. I did my 10 years there.

ANSEN: Were you there that long?

SCORSESE: Yeah, but after the first few years, I’d come back and forth to New York. I liked making movies out there; I just didn’t care for living our there too much. I need the City. And I always felt my values started to get a little changed, because the whole town makes movies and everything revolves around movies. When you’re invited to the “wrong” screening…I mean, how could there be such a thing as a “wrong” screening in the first place? When you start thinking like that, your values begin to get messed up. You’ve go to remember what’s important. You’ve got to protect whatever creative talent you have left. You have to put yourself in a situation, a lifestyle, that makes you do the work. Even if it’s a monastery.

ANSEN: What form did it take for you?

SCORSESE: Well, I don’t want to get into specifics…I was self-destructive in many different ways. I think you can see it reflected in Mean Streets and Taxi Driver and Raging Bull. It’s just a behavior of spirit, a violent spirit. I’m not saying hitting people, but an anger. I think the anger is there. Now I’m trying not to let the anger and the violence that erupt take over my life. I guess it comes with the growing process, I don’t know. A little mellowing.

ANSEN: Where do you think that anger came from? Was it always in you?

SCORSESE: Absolutely, it was always in me. I don’t know exactly how or why. Maybe coming from a neighborhood that’s pretty rough and not being able to defend myself. The only way I was able to defend myself was to be able to take punishment. Then I got a lot of respect. They said, “Oh, he’s okay, he can take it. Don’t hit him.” The guys were pretty big, and I had asthma.

ANSEN: Well, that would be conducive to a certain amount of anger.

SCORSESE: Yeah, it’s the old “I’ll show them.” But the problem with anger is that it’s so consuming. You’ve got to take it easy on yourself at a certain point. I get a lot of it out, actually, in the editing. My editor, Thelma Schoonmaker, and I are in a room and nobody can come in because it sounds like we’re fighting. We’re really letting it all out, almost like therapy. People hear us and are afraid to come in. It’s really good.

ANSEN: Do you make movies in your dreams?

SCORSESE: No, I don’t. Usually, the thoughts come in a half-relaxed state. I don’t really dream them. A lot of thoughts I keep on Post-Its. I keep sticking them around the house and collect them at the end of the day. Post-Its are probably the most incredible invention. They stick. Yellow Post-Its.

ANSEN: What are your favorite movies? Do they change all the time?

SCORSESE: No, they seem to fall into the same category. Citizen Kane. The Red Shoes. 8 ½. Senso. And The Searchers. Those five, really, are the ones I’m obsessed with. Those pictures just will never change for me.

ANSEN: How did you respond to Bertolucci when you first saw him?

SCORSESE: Oh, Bertolucci was everyone’s idol then. In 1965, I saw Before the Revolution and decided I was going to make a feature through NYU. It had a lot of the attributes of Before the Revolution. I saw that film maybe 13, 14 times, studied it over and over again.

ANSEN: Did Godard and Truffaut have that kind of influence?

SCORSESE: Oh, absolutely. Godard and Truffaut taught me a sense of freedom. Especially Jules and Jim. That’s the one. I love Goddard, but he was always a little too cerebral for me. I always felt stupid, real dumb. But Jules and Jim, you don’t feel dumb, you just feel emotion, you feel incredible love.

ANSEN: You play a part in ‘Round Midnight. How do you like acting?

SCORSESE: Oh, it was terrifying. I felt like I was too heavy…a bald spot…I talk so fast people laugh at me. So I find it embarrassing. I find it humiliating. I did it as a favor for Bertrand Tavernier. It was an honor to be in it, but I feel bad about it. I feel people are a laughing at me.

ANSEN: Does criticism ever illuminate anything for you about your own work?

SCORSESE: Sometimes. There are people who actually go through the work and find similar themes, I find that interesting. But critics who talk about “the tracking shots lack moral conviction,” things like that, I don’t know what they’re talking about. That sort of thing drives me crazy. Or “the medium shots lack humility.” That’s another one that get’s me. Who wants humility? Forget it. You’re not going to get it here.

ANSEN: How important would it be for you to get an Oscar nomination for The Color of Money?

SCORSESE: That would be nice. I accept all awards. I like them. Don’t forget, as a kid I watched the Academy Awards on television and always wanted one—or several—like one of my favorite directions, John Ford. He won six. On the other hand, Orson Welles, who’s on the top of my list, didn’t win any. Alfred Hitchcock didn’t win any. Howard Hawks didn’t win any.

ANSEN: How do you feel about the new movie? Is it as personal as the others?

SCORSESE: I don’t know, I’m too close to it now. It’s very personal for me, but how personal it is compared to the other pictures, I don’t know yet. It’s still one of my babies.

ANSEN: A lot of people have trouble with the last third of the movie. They don’t feel the Paul Newman character needs to be redeemed. They like him the way he is. It doesn’t seem to be a life-or-death matter.

SCORSESE: Well, that says more about them than about the movie. You see, the film is basically a mini morality play.

ANSEN: Maybe you underestimate how corrupt the audience has become.

SCORSESE: Yeah. Look how corrupt they’ve gotten, with films like Top Gun and Rocky. They have been corrupted; it’s a pity. What I mean by that is they don’t have enough. They don’t have enough appetizers and enough side dishes and enough incredible, delicious little morsels to nourish their minds and souls. They’re being short-changed, the audience. They’re going for easy emotions, and it’s a pity. I really feel that.

ANSEN: How do you feel about After Hours now?

SCORSESE: I like that movie a lot. It’s the only movie of mine that I can watch over and over again. It’s so funny to me. Someone called it a “farce of the subconscious.” That’s what it is. Like a French farce. Here we have the timing down to psychological elements and sexual dread. I thought it was a whole metaphor for the way we are living and for what I went through in L.A. trying to get The Last Temptation made. I just had a ball with it, because it meant so much to me. I asked myself, “Can I make a picture with the same energy I had when I was 32?” And I did.

ANSEN: The Moral Majority put pressure on Paramount not to make Last Temptation. This mixture of religion and politics is getting scary.

SCORSESE: It’s very dangerous. It’s a tricky area. You can be born-again and believe in Jesus, believe in Jesus’ ideas and try to live them out, without becoming totally intolerant of other people. That’s what this country has got to understand. And believe me, sometimes God picks you up and tells you, “You’ve been messing around now. You’re going to have to stop this, stop that, but I’ll give you another chance.” And you wonder why you’re given another chance. It must be for something; it must be to celebrate life.

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY RAN IN THE JANUARY 1987 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

New Again runs every Wednesday. For more, click here.