New Again: John Malkovich

Actor and director John Malkovich first appeared on the screen in A Wedding (1978) and has yet to slow down since. Known for roles in films such as Dangerous Liaisons, In the Line of Fire, Places of the Heart, Being John Malkovich, and more recently, Burn After Reading and even Penguins of Madagascar, Malkovich’s versatility and intriguing nature allow him to remain a staple of the screen. Next year, he will appear in Unlocked and Deep Water Horizon, and yesterday, the Illinois native celebrated his 62nd birthday. So in honor of his continuous success, here we revisit his cover story from Interview‘s March 1989 issue.

Wild Card

By Becky Johnston

From Steppenwolf’s True West to Dangerous Liaisons, spellbinder John Malkovich has brought intensity and whimsy to all his roles. Becky Johnston found him well turned out, as usual, in his new apartment in Los Angeles.

Chances are if John Malkovich hadn’t fallen in love in college he’d be fighting forest fires in some national park right now. At the age of 19, Malkovich left his hometown of Benton, Illinois, packed off to nearby Eastern Illinois University and enrolled in the environmental studies program. He wanted to be a forest ranger, he says, “Because at that age not knowing what you want to do, you go into the family business.” And the family business was ecology: Malkovich’s father was a conservationist who edited Illinois Magazine, a scholarly environmental journal. Malkovich remembers childhood weekends spent camping in the woods, hunting for arrowheads, canoeing up the Ohio River. It was an unruly ménage of seven: five restless kids, mom and dad. “We were always charging off to look at the eclipse from the Kentucky light,” he says. It sounds idyllic, but in the next breath he’ll tell you that the entire family fought like wild animals all weekend long.

Despite the occasional bloodletting, those trips gave each of the children a solid appreciation of natural beauty. “We knew every kind of flower, plant and rock formation,” he recalls. But by the time Malkovich reached college and was deep into his required courses of botany and biology, he had acquired an appreciation of other kinds of natural beauty—mostly women. He became infatuated with “the coolest girl on campus,” says his fellow classmate and close friend Russ Smith. “She was taking theater classes and John followed her into the drama department one day and said, ‘Hmmm. I think I’ll try this.'” When I asked Russ Smith if even then Malkovich displayed a flair for the dramatic, he replied: “Oh, there was most definitely an actor there. He was very self-conscious; he wore ’40s gangster-style clothes and platform shoes. His hair went down to his shoulders and was spiked on top like Rod Stewart’s…It was clear even then that John was not a guy who was going to be sitting in a treetop with binoculars, looking for forest fires for a living.”

So he transferred to Illinois State University and began studying theater. It was at Illinois State that Malkovich was introduced to a small cadre of drama students who eventually became members of the Steppenwolf Theatre Company. Gary Sinise, who formed the group in 1974 with drama students Terry Kinney and Jeff Perry, caught Malkovich in a production of The Man Who Came to Dinner. “It was the stupidest performance I’d ever seen,” said Sinise. “I thought, we’ve got to get this freak into our theater.”

Malkovich joined and in 1980 Steppenwolf moved to its own theater in Chicago. By that time its membership had grown to include Malkovich, Sinise, Kinney, Perry, Tom Irwin, Laurie Metcalf, Moira Harris and Glenne Headly (whom Malkovich married in 1982). Malkovich’s chum Russ Smith came on as a producer. “There wasn’t an intellectual among us,” says Smith. “It was a musky, incestuous group that had complete disdain for other types of theater. I think Steppenwolf was an attempt to create a refuge from the rest of the world. The rest of the world had careers. We just wanted to act and be irresponsible.”

In 1982, Malkovich’s quietly building career advanced to fast-forward with Steppenwolf’s New York production of True West. Malkovich’s performance as the crotch-scratching, nose-picking, terminally juvenile Lee won him the Clarence Derwent Award for outstanding newcomer, an Obie and the Joseph Jefferson Best Actor Award. People compared him with Brando and Dean. Soon after the play closed, Malkovich flew to Thailand to portray an American photographer on Roland Joffe’s The KillingFields. He hasn’t stopped moving since. He went on to play the blind Mr. Will in Robert Benton’s Places in the Heart (for which he received an Academy Award nomination for Best Supporting Actor). Opposite Dustin Hoffman in Death of a Salesman, Malkovich won a Drama Desk Award for his performance as Biff. Two years ago he appeared on the stage in Lanford Wilson’s Burn This. He has starred in films directed by Peter Yates (Eleni), Volker Schlöndorff (Death of a Salesman), Paul Newman (The Glass Menagerie), Steven Spielberg (Empire of the Sun), and Susan Siedelman (Making Mr. Right). He most recently donned a powdered wig and brocade knickers to play Valmont in Stephen Frears’s Dangerous Liaisons.

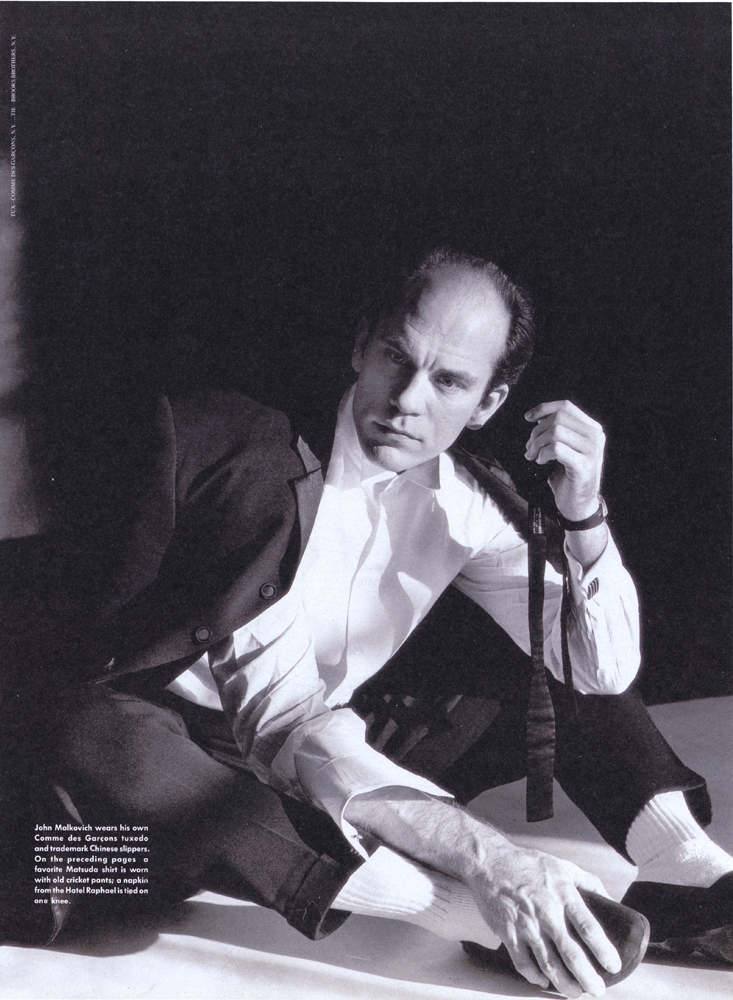

In person, Malkovich is self-effacing and a bit spacey. He speaks softy, almost in a whisper, and measures his words carefully, although his sentences are usually spiked with countless “sort ofs,” “kind ofs,” “you knows,” and “I means.” He has a droll, flat Midwestern wit: everything seems cheery; then he levels the whole works with some darkly cynical last word. “John is a fascinating combination of opposites,” says Jeff Perry. “He’s very introspective, very intelligent but there’s a bit of the class clown in there, too.” Or, as Malkovich himself would say, “I guess I’m kind of curious.” Malkovich was wearing a black-and-white Kenzo suit with checked-and-plaid jacket, checked pants, and black Chinese slippers with white socks when he talked to me in his new apartment.

BECKY JOHNSTON: Let’s talk about sex.

JOHN MALKOVICH: O.K. Well, um… [long pause] Sex, as I remember it, is probably… [pauses] I couldn’t start with a harder question at this point in my life. I don’t know what else I can say.

JOHNSTON: Well, I have a less confrontational question: what is it about women that you love, and what is it about women that you don’t love?

MALKOVICH: I have probably more female friends than any man I’ve met. What I like about them is that almost always they’re generally mentally tougher, and they’re better listeners and they’re more capable of surviving things. And most of the women that I like have a haunted quality—they’re sort of like women who live in a haunted house by themselves.

JOHNSTON: Why do you like that quality?

MALKOVICH: Because along with the good qualities, if someone isn’t vulnerable I can’t be around them to a certain extent. And I don’t mean vulnerable to me or vulnerable to me in a sexual way. I just mean vulnerable, period. They sort of have to be both. That quality exists in a lot more women than men. I have probably four or five male friends who have a real strong masculine side but some degree of a feminine side, too. They’re pretty rare, whereas I think women with a masculine side are much less rare. I know I have a fairly strong feminine side. I find myself really distanced from male behavior. You know, you go and play basketball, and it’s like, “Fuck you, you cocksucker! Eat shit! Wimp!” I can’t really identify with that.

JOHNSTON: Yet as an actor you seem to have an enormous amount of anger that you can tap into and use to great effect.

MALKOVICH: Yeah, well, for the first time in my life I’m sort of studying that right now, trying to figure out what the root cause of it is. Certainly the characters I played in True West and Death of a Salesman and Burn This all had an exceptional amount of buried anger, and doing those plays kept me on and even keel, sort of emotionally on an even keel. Since I’m not sure that I can actually act, I have to do those things; I can’t pretend as other people can pretend. I don’t seem to have the facility. So doing a play where you come out and, you know, everyone’s a motherfucker, everyone’s a nigger, everyone’s a cunt, everyone’s a potential problem or adversary to identified and stomped on—it’s a good thing, in a weird way, as a form of therapy.

JOHNSTON: To go back to the original question, what is it about women that you don’t like.

MALKOVICH: [long pause] They hurt. [pauses] And they have a native meanness, unfortunately, that I don’t think men have. Maybe a lot of it is their feminine side, and that’s equated with something soft or pillowy, but there’s something—sometimes—mean in them, as opposed to maybe forceful or angry or direct.

JOHNSTON: Valmont, the character you play in you latest film, Dangerous Liaisons, plans elaborate emotional games to seduce women.

MALKOVICH: Well, the thing about Valmont, I think, that’s widely misunderstood is that he’s perceived to be a misogynist. But of course he’s really a victim. He is completely obsessed with women, in all ways and not just sexually, which is not really a major theme for him. For him it’s a kind of battle for the soul—it’s a battle that, as a man, he’s not equipped to win.

JOHNSTON: One of the central conflicts or tensions in the film is the schism between love and sex. Valmont is always playing for sex. What eventually undoes him is that he falls in love.

MALKOVICH: Yeah. The reason I think it’s such a seminal novel about men and women is that it’s very much about self-delusion. He and Merteuil have deluded themselves into thinking that love is not a possibility on this planet. Not a real thing. And when he finds out that’s not true, it destroys him because it destroys his self-image, and he dies. The original source material is unbelievably sad.

JOHNSTON: And contemporary.

MALKOVICH: Yeah. Sex… It’s very funny thing because it’s actually not a game. But there’s always that wish to conquer and to be conquered. And it should be something more, in some way. It seems very difficult to achieve. One of the reasons both the book and film are so amazingly contemporary is that the battlefield is remarkably unchanged: the armies are much the same and the war is the same, too. And there is absolutely no more of a sense in 1989—probably less—that men and women have found a way to coexist. That’s why the story appeals to me so much.

I mean, it ends rather badly. But Valmont is redeemed in a certain way. He says: “I’m sorry. I can feel this. I’ve made a terrible mistake.” Once, when we were doing the film, I was playing Scrabble and we looked up the definition of love. And the definition was, I believe, “a destructive force.”

JOHNSTON: Is that what you believe?

MALKOVICH: No. I think Faulkner had the best definition, which is that “love is a bond purchased without design, which matures willy-nilly and can be recalled by whatever issue the gods happen to be floating at the time.” That would seem to me to be the most accurate, if unfaceable, definition of the term.

JOHNSTON: Let’s talk a bit about your early years as a stage actor. You studied theater at Illinois State and later were one of the founding members of Steppenwolf Theater Company in Chicago.

MALKOVICH: Gary Sinise and Terry Kinney had already formed the group. They had seen some things I did in college, none of which were terribly successful, but they asked me to join in 1976 and I sort of felt, “These assholes with their theater—sure.” I didn’t really know them and what I did know of them I didn’t like. They were like the Angry Young Men, always complaining about one thing or another. And I really thought, “Maybe I’ll do this for a while, a couple of weeks, or maybe a couple of months.” I felt that would be all I could stand. That was 13 years ago. And you know, they’re still my closest friends. We sort of started rehearsing the day we left college.

JOHNSTON: Was there any kind of central idea behind the group? Some kind of statement of purpose or aesthetic credo?

MALKOVICH: Yeah. Competition. [laughs] I think what we tried to do at Steppenwolf was simply to say, “We’re sorry if you can’t feel anything, but we’ll make you feel if it’s the last thing we do.” I mean, is it still possible to move people? Is it still possible to challenge them? And our work was always vicious in that way. We were never cute and I think that still holds true. Everyone always likes everyone’s work and that’s what also kept it together. There was very much a shared sensibility about planetary perceptions, but also a respect for one another’s work.

JOHNSTON: There was a fairly tense period in Steppenwolf’s history when it seems as if the group might split apart. I’m referring to the time in 1982 when you and Gary Sinise decided to move True West to New York and the rest of the group was strongly opposed to it.

MALKOVICH: Well, that was a very odd time because I was, I think, about 28 or 29 and I didn’t really give a fuck about going to New York. We were making $100 a week and doing what I thought was generally good work. But the reaction to the possibility of our going was virulent and possessive and strident that it really changed my mind.

JOHNSTON: What? It made you want to go even more?

MALKOVICH: I didn’t want to go at all, but I thought, “Well, if you’re that upset about this, there’s something kind of rotten somewhere. Why is this bothering you so much?” I never expected the play to be successful. I packed a bag with a couple of days’ clothes and took one book, thinking, “Well, this will last me through rehearsals.” I thought the play would run about one day we’d go back and I wouldn’t have cared. That’s the funny thing about life because those decisions come back to haunt you.

JOHNSTON: In addition to acting, you’ve directed several plays: Balm in Gilead, Arms and the Man, The Caretaker, Coyote Ugly. As a director, how do you try to get a performance from the actor?

MALKOVICH: I approach it all by instinct, just by things I feel. I don’t have a great intellect, and I can’t compete with people who do. I feel certain things. And all I know, and all I can do, is what I feel.

JOHNSTON: So you wouldn’t say you worked from a preconceived plan. There wasn’t a method.

MALKOVICH: No, no. It seems whenever I’ve had a method or what I perceived to be an intellectual groundwork of some sort—a kind of game plan—it’s always been the most morbid failure. I just have to say, Now it’s time to leg-wrestle, or to make farting noises or to sob. And it’s very difficult to explain where those impulses come from—I don’t know—but I feel they usually work.

JOHNSTON: What would you describe as the major difference between acting and directing?

MALKOVICH: Well, when I have failed as an actor I’ve always thought it was my fault. But when I direct something, I wouldn’t want the actors to think it was their fault. In fact I would have a tendency to think I had either miscast them or simply hadn’t directed them properly or been helpful enough. There’s no worse feeling in the world than realizing the play you’ve directed doesn’t work.

JOHNSTON: What is it that makes a play work or not work?

MALKOVICH: I don’t know. I did a play of Chris Hampton’s who wrote Les Liaisons. The play was called Savages. It had some really good actors in it, all of whom chose that particular play to give the only bad performance of their lives. I directed it, and it was just horribly directed. It never got better. I would go every night, take four or five pages of notes and try to incorporate those notes the next night. It just got worse and went on spiraling downward for two months. I never did figure out what the fuck was wrong with it.

I had all my friends come and watch it. They would just sit there and say, “I don’t know why it’s so bad.” And I’d say, “Well, do you like the play?” They’d say, “Yeah, I think it’s a great play.” “Well, what’s wrong with it?” “I don’t know. It’s just all wrong.” It was horrible.

And to watch actors you like, or care about flounder is very painful because you feel responsibly. You are responsible. But with acting it’s your neck up there in the end. And if you think the director can’t help you it’s one thing. But if you feel they’re reining you in when they need to be giving you some rope, or vice versa, then I just don’t tolerate that. I mean, I have never tolerated it. The very few times it’s come down to that I’ve just said “hire someone else, cause I simply won’t do it… I won’t be caught dead doing it.”

JOHNSTON: You were once quoted as saying about your approach to acting: “A method actor might use emotional recall, reach into his psyche, or think about the beat. I can’t do any of that. I just start laughing and crying. The more I think about it, the more complicated it gets, and it shuts me off completely.”

MALKOVICH: Mmm. Yes, well, I think that’s pretty accurate. [pauses] It would appear to me that, for example, if you’re doing the last scene of Death of a Salesman—granted you do it a hundred times, three or four hundred times—you can fail. That’s just sort of a natural thing. But if you have to prepare emotionally for that scene, or work yourself up, well, then I don’t think you’re an actor. I mean, what the fuck is there to prepare? It’s the primal scene—your father and your mother and your brother, period. There’s isn’t anything else. Those kinds of things don’t require thought. They require… disciplined feeling. It’s just a matter of lifting up your head and letting go.

JOHNSTON: But that’s the mystery of it: lifting up your head. How you arrive at the point where you can do that?

MALKOVICH: I think it’s a natural gift. The one natural gift I have is easy access. That’s the only natural I gift I have at all. You have to have that, the third eye.

JOHNSTON: Gary Sinise said that when you first started acting you used to speak so softly, the people in the front row had trouble hearing you; that you were such an introspective actor, you forced the audience to come to you. He said part of your growth as an actor was learning to come out of yourself, to, in a sense, be more generous to the audience.

MALKOVICH: Well, Gary said that. I also think that the parts changed. I wasn’t playing brooding, troubled people anymore.

JOHNSTON: You’ve been quoted as saying that you based the character of Lee in True West on your older brother, Danny.

MALKOVICH: Yes. Well, I think my brother beat me up every day until I was about a sophomore in high school. Every day, without fail.

JOHNSTON: Did you ever provoke him?

MALKOVICH: Something about me must have provoked him. He’d just sort of sit on my head and fart, or spit on me, or drool on me, or kick me or whatever it was. And I was always hitting with the bread roller or going after him the butcher knife or poker. It never stopped, and I really don’t know why.

JOHNSTON: What’s your relationship with him like now?

MALKOVICH: Great. I spent Christmas with him. He’s very funny and charming. I’ve always loved him. I don’t know why he did that. [laughs] I don’t know.

JOHNSTON: Tell me a little bit about your family.

MALKOVICH: Well, my father’s dead. He was a conservationist. He was sort of very pretty and very odd, quite dark. I think darker than I ever realized, in some ways, but very funny and charming. He seemed to be a cross between Bobby Knight and Mark Twain. Really extraordinary. I really liked my father. My mother has a master’s psychology, and we’ve always called her “Frog” since the time we were really little.

JOHNSTON: Why did you call her Frog?

MALKOVICH: Because she sounds like a frog. Did you talk to her?

JOHNSTON: No.

MALKOVICH: Oh, god, she’s funny as hell. She’s really very funny. And very bright. She could tell you the latest thing in The Atlantic Monthly, or what C.S. Lewis wrote, or the B-52s’ new video or what she doesn’t like about U2 or how many yards Bo Jackson got last week. My sister Melissa is very smart and really tough. I’m probably most like my sister Amanda, who teaches school in Miami and is also very bright but somewhat damaged, I guess. And then my sister Becky is the youngest. She’s really funny, and she lives nears my hometown and has a baby.

JOHNSTON: Your sister Melissa said the five of you were constantly brawling, and it was a rare meal that when by without beef stew being thrown across the table.

MALKOVICH: Oh, yeah. I’ve stuffed a few meals down my sisters’ throats with a fork or knife, or beat the senseless or whatever, usually because I didn’t like the way they treated my mom.

JOHNSTON: How would they treat her?

MALKOVICH: Dinner would come and one of my sisters would say, “What the fuck is this?” And my mom would say, [imitates his mother’s voice] “But that’s my tuna casserole.” My sister would say, “You can my eat my butt out if you think I’m gonna digest this thing one more time,” and then she’d pitch it into the garbage. Then I’d just flip. So, yeah, it was a volatile family.

JOHNSTON: When you were growing up were closer to your mother than you were your father?

MALKOVICH: [pauses] I think so. My father could be very distancing. My clearest memory is of him squatting, watering plants for hours and hours at a time, completely silent. He was very self-contained; my mother was more outgoing and chatty and social. I’m certainly more like her.

JOHNSTON: Your parents apparently never left home. They had no friends. That’s what both Melissa and Amanda told me.

MALKOVICH: They had two friends that I remember, two old conservationists named Bill and Mary Farley, who came around, but otherwise they had no friends whatsoever.

JOHNSTON: Strange.

MALKOVICH: Yeah. They always just sort of hung out with us or with each other. But my father was gone a lot because he was on boards and things, doing environmental work all the time. It was difficult to get my ma out of the house.

JOHNSTON: Your sisters also said that you were enormously charismatic and popular as a kid and that there were usually 10 to 20 of your friends hanging out in the house.

MALKOVICH: Well, it was my parents who were popular with my friends. They usually came to see them, not me. My friends just liked to be with them, I guess. It’s weird because my parents weren’t hip. I mean nobody came to our house drunk or high. If they did, my dad would say, “Get the fuck out of her before I beat you to fuckin’ death.” But if you wanted to come over and shoot the shit, play cards, or talk or just laugh that was fine.

JOHNSTON: There was a period in high school when you were extremely overweight?

MALKOVICH: Oh, all the time I was growing up—about 17 years. I was just fat. I liked my PB&Js and just kept eating.

JOHNSTON: But during that time you were also playing football and were very athletic.

MALKOVICH: Football and baseball. That didn’t really infringe on my eating problem, I’m afraid. Plenty of time for doughnuts.

JOHNSTON: Another thing both your sisters said was that since childhood you’ve been obsessed with games. All kinds of games: cards, board games, sports.

MALKOVICH: I think probably when I was little, after my brother turned on me, I just had to play by myself or with myself. I’ve always done that. I think either it’s some kind of weirdly competitive streak or it takes my mind off whatever’s bothering me.

JOHNSTON: Were you much of a reader as a kid?

MALKOVICH: My mom brought me home Native Son when I was in the third grade. I’ve always been an avid reader. Everyone in my family read a lot. Considering we were from a little town, we were pretty literate.

JOHNSTON: Did that make you seem strange to the townspeople?

MALKOVICH: I would think so. I mean, we certainly were freaks in that town. We would be freaks anywhere, I’m afraid, but we were too sick to travel.

JOHNSTON: What was your hometown, Benton, Illinois like?

MALKOVICH: Magnificent. I loved it. One doesn’t know if one had a happy childhood or not. I don’t really know what it means. I loved my town and the people there, whom I found both amusing curious. It was very small, and we didn’t have a swimming pool or anything to do. We just drove around North Main or South Main and honked our horn. That’s really all we did.

JOHNSTON: Your sister Amanda told me that during high school you went through a religious phase.

MALKOVICH: Mmm. Yes. It would appear to me I’ve gone through life searching for something, even when I was heavy. [laughs] I don’t have much to say about that except, yes, I was very religious.

JOHNSTON: Since 1984, you’ve appeared in seven films and countless pieces have been written about you. How does it feel to be such a public figure?

MALKOVICH: [long pause] It’s a wonderful life. [laughs] I’m not sure. There are many, many benefits to being known for whatever it is you do. To deny that would be sort of asinine and vulgar. But I don’t really have a comprehension of being a public figure. It’s a little bit hard to have personal things subject to public scrutiny, and it’s a pressure that other people aren’t under, but then they’re under a lot of pressures that we’re not under.

JOHNSTON: Have you had to changed your way life at all?

MALKOVICH: No, not really. People come up and say, “I loved you in this or that,” but I’m very detached from that in some way, because I don’t feel it has anything to do with me. I mean, I am not this person or that character or this sort of work machine; I’m something apart from that, but I’ve yet to figure out exactly what that is.

JOHNSTON: Do you read reviews of your work?

MALKOVICH: I hadn’t read reviews in a couple of years. I read some of the reviews of Liaisons. I think that’ll cure me for another couple of years. But no, not too much. Reviews are destructive by their very nature. I didn’t read any reviews of Burn This because I knew that there quite a few critics who would not be amused. And why bring to stage with you? Because all you have is the writer’s imagination. You have a very limited time to take this imaginary person and bring the details of their life, as you perceive them, to life. You attempt to do to that as fully and as vibrantly as you can. It’s depressing to read how much you’ve failed. And it’s not even particularly instructive or necessary to read how you succeeded because in the end don’t you have to judge that?

JOHNSTON: Was there ever anything you wanted to do aside from acting and directing?

MALKOVICH: For a while I wanted to be a professional baseball pitcher, and then I wanted to be a musician and then sometimes I think I’d like to start a store for gift-wrapping Christmas presents…But I feel I could do most things I set my mind to, except mechanical things, I’m not very good at that.

JOHNSTON: You seem to have a fairly consistent romantic history. All the women you’ve been involved with have been actresses. You were involved with an acting student Eastern University, you had a two-year relationship with Steppenwolf actress Laurie Metcalf and you married Steppenwolf actress Glenne Headly. Did that create any tension or competition in the relationship?

MALKOVICH: I have never felt that Glenne was competitive. I always felt she was just very interested in what I did and very supportive. And with Laurie I felt the same thing. And the girl I lived with in school probably felt the same way. They were all very talented, which is part of what attracted me to them in the first place. If they weren’t exceptionally gifted, and if they didn’t know I felt that way about them, it probably would have been a problem. Anyway, being threatened is more a masculine trait than a feminine trait. So I would say that if anyone had felt threatened, it would have been me.

JOHNSTON: Were you?

MALKOVICH: [long pause] Yes and no. Part of what is threatening is the damage that can be incurred over the course of a career or a life. I was sometimes threatened for them in the sense that you say: She’s really great. Why doesn’t she have a job? So I think maybe I was threatened in a protective way. Maybe. And then sometimes, yeah, their work can take them away from you. If you don’t see someone for months or years at a time… But I never wanted to be with someone who just hung around the house.

JOHNSTON: What actors outside of the Steppenwolf group do you admire?

MALKOVICH: There are actually a lot. I think Meryl Streep is awfully good. I’m very fond of Judy Davis. Isabelle Adjani. I thought Drew Barrymore was great.

JOHNSTON: What about men?

MALKOVICH: Well, I like the same ones everyone likes, I assume. There are so many.

JOHNSTON: But are there any actors you would say have influenced your work?

MALKOVICH: Not that I know of. But I think we all influence one another. That is, if you grew up watching Montgomery Clift—which I did not—you respond to hum in a certain way. And if you grew up watching Brando—which I also did not—then you respond to him in a certain ay. But I didn’t actually grow up watching anyone, because I didn’t have any money.

JOHNSTON: Do you see many films now?

MALKOVICH: No. It’s rare that I feel I absolutely have to see a film.

JOHNSTON: Do you go to many plays?

MALKOVICH: No, I don’t get out a copious amount. The theater is so disappointing, really, that it’s hard to go again and again. It’s just too heartbreaking. I’d rather watch football or play a game or read.

JOHNSTON: Do you have any favorite authors?

MALKOVICH: Yes. Faulkner. I like many others a lot, but I don’t think anyone wrote better than he did at his best. I read modern novels, some classics. The usual sort of people. When I was growing up I liked Salinger, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Mark Twain. But Faulkner’s my favorite. The one book I have here is his.

JOHNSTON: You don’t have a library?

MALKOVICH: No, not here.

JOHNSTON: Not here, meaning Los Angeles. You’ve recently moved here, right?

MALKOVICH: Mm-hmm.

JOHNSTON: How do you feel about that?

MALKOVICH: Well, I feel Californian. [pauses] I’m not sure. I’ve only been here a couple of months. I like it fine so far. I don’t want to be in New York that much anymore. It’s a little too much for me.

JOHNSTON: What odd jobs have you done? I remember reading somewhere that you used to sell office supplies in Chicago during the Steppenwolf days and that you drove a school bus.

MALKOVICH: Yeah, I sold office supplies for three our four years; then I was a cabbage cutter; I painted houses; then I drove that bus for an exclusive Jewish school in the suburbs.

JOHNSTON: There’s a very funny story about a nerd and geek poll you used to conduct with the schoolchildren.

MALKOVICH: Yeah, well, I used to do a lot of things to the kids. Like say, “Let’s talk about Nietzsche today.” That was about the best job I ever had, I think. First of all, they were really funny and remarkably grownup, but in a kind of embittered way. I would hear remarkable things all the time, once, I remember a boy about 10 years old saying that when he looked back, he realized his life had been a pack of lies and he wanted to wipe the slate clean. One would just be constantly astounded by what they had to say. I would take a freak, geek, and nerd poll. They had to stand up and say which of the three they were that day.

JOHNSTON: All of them had to do it?

MALKOVICH: Yeah. They were bitter, but they were interested. Once, when I was teasing them, this little girl got up. Her face got really red and choked up with rage, and she started screaming, “Don’t you understand? Hasn’t it got through to your head why no one sits at the front of the bus? Don’t you understand? You’re the freak!”

JOHNSTON: That’s kind of embarrassing, coming from a 10-year-old.

MALKOVICH: Yeah, it is sort of sad to hear that from a fourth grader. Then there was a kid who rented out Playboys and Penthouses. My clearest memory of him is on the last day of school, when I took the kids to the Dairy Queen. They complained bitterly about the spending limit I had set. The boy who had rented out Penthouse was talking about a school production of The Wizard of Oz. With an incredibly sour look on his face, he threw something on the floor and said, “Jesus Christ. They laid an egg!” I said, “What do you mean?” He said, “The Wizard of Oz! It was a piece of crap!” He was in third grade and was already a major drama critic.

JOHNSTON: Let’s hope he’s not working for a major newspaper or magazine yet. How do you choose projects? On what basis do you pick something?

MALKOVICH: Just dumb luck. Or just dumb… [long pause] You know, at the risk of sounding completely asinine…you want to say something Faulkner said when he won the Nobel Prize: “I feel that this award was not made to me as a man, but to my work—a life’s work and the agony and seat of the human spirit, not for glory and least of all for profit, but to create out of the materials of the human spirit something which did not exist before.” And, although I will never have a fifty-thousandth of the sort of talent or vision he had, I still would like to create things that didn’t exist before. That’s what you try to do, it seems to me.

JOHNSTON: There’s another quote from an interview you have a few years ago: “Sometimes I think my work is unimportant and I wish I could do something else.”

MALKOVICH: Uh-huh. [long pause] Yeah. I feel that way sometimes. But maybe all work’s unimportant if you think of it in terms of the fact that the sun’s burning out. I mean, our existence is very curious, isn’t it? [pauses] One has to agree with Thornton Wilder in the end, you know—in Our Town, when Emily asks him, “Does anybody really understand?” And he says, “Saints and poets, for a moment, maybe.” I mean, that appears to be quite true. And you may think that someday what you do will be an aid. [pauses] I’m sure when J.M. Barrie set out to write Peter Pan he didn’t really think about things like that. Maybe he did. But he changed the way things are perceived. In Peter Pan, when Peter comes back to get Wendy after hanging around with the Lost Boys, it’s a bit late, and that’s terribly lifelike. But there are lessons there if we can see them and learn. You know, in the best things there is great hope somehow, even if it’s hope of how not to be. And I think that’s why I do what I do—to give people hope.

THIS INTERVIEW WAS THE MARCH 1989 COVER STORY OF INTERVIEW.

New Again runs every week. For more, click here.