New Again: Harry Dean Stanton

The late film critic Roger Ebert once said that any movie with Harry Dean Stanton in a supporting role cannot be a bad movie, and based on Stanton’s filmic credits, Ebert was onto something. The acting great began his career at age 20 and has since appeared in an array of classics, including—but in no way limited to—Alien (1979), Paris, Texas (1984), Pretty in Pink (1986), and The Green Mile (1999). He has worked with the likes of Francis Ford Coppola, Sam Peckinpah, and Martin Scorsese.

Now, with 70 years of work to his name, he’s still going strong. Variety recently announced that he will be starring in John Carroll Lynch’s directorial debut Lucky. The film will also feature David Lynch, meaning that we can expect not one, but two reunions of the frequent collaborators in the near future (Stanton is also set to revive his role as Carl Rudd in Lynch’s Twin Peaks next year).

In honor of Stanton’s 90th birthday tomorrow and remarkable cinematic tenure, we’ve reprinted his Interview feature from January 1991. He’s as cool as you’d expect, and casually discusses his golf rounds against Jack Nicholson, his musical performances with Bob Dylan, and his stint as a model for Rei Kawakubo with Comme des Garçons. —Ethan Sapienza

Harry Dean Stanton

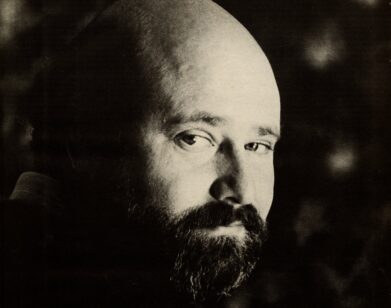

by Ingrid Sischy

When a movie actor becomes a star in the early evening of his or her career, it sheds a new light on the day that has gone before. Harry Dean Stanton was a 57-year-old character player, for 27 years an impersonator of cops, heavies, and best friends, when Sam Shepard and Wim Wenders asked him to play Travis in Paris, Texas [1984]. Stanton’s portrayal of the gangling, hollow-cheeked wanderer who blindly scours the southwestern wastes for his wife (Nastassja Kinski), and is eventually redeemed by their mutual love for their son, was mesmerizing; he has been an existential icon ever since. It was a consecration that gained from Harry Dean’s own long search for a seemingly elusive recognition. He wasn’t the only difficult ’50s kid to come home in the ’80s: his Paris, Texas co-star Dean Stockwell and Dennis Hopper were also in the process of being reborn, via David Lynch’s Blue Velvet, and it was no coincidence that Harry Dean turned up last year as the nervy, love-struck detective in Lynch’s Wild at Heart.

Born to an itinerant Southern Baptist family in West Irvine, Kentucky, in 1926, Stanton nurtured his gift for singing during a hard Depression childhood. After naval service in the Pacific in World War II, he majored in drama at the University of Kentucky, acted at the Pasadena Playhouse, and toured with the American Male Chorus; music still plays a major role in his life. He began his Hollywood career in Westerns—Tomahawk Trail [1957], The Proud Rebel [1958]—and spent much of the ’60s and ’70s frustrated by the roles he got. No matter that Hollywood was slow to discover the gentleness in Harry Dean’s persona or that the parts themselves were often small, he shaded each picture he was in. His choices were generally excellent, and it seems unlikely that any other modern American actor has made so many hip movies: Cool Hand Luke, Two-Lane Blacktop, Cisco Pike, Dillinger, Cockfighter, The Godfather Part II, Rancho Deluxe, The Missouri Breaks, Alien, Wise Blood, One from the Heart, Repo Man, The Last Temptation of Christ, Twister.

The only surprise is that so far he hasn’t brought his battered nobility and young-old face to depictions of American history (he has expressed an interest in playing the pacifist senator Henry Clay, a fellow Kentuckian, and there is no one else who would be right for John Brown). That he remains one of our most romantic icons is summed up neatly Deborah Harry’s serenade to him on a recent record that begins: “I want to dance with Harry Dean…” —Graham Fuller

INGRID SISCHY: Harry, tell me about the movie you’re working on.

HARRY DEAN STANTON: It’s sort of a gangster, Prizzi’s Honor-type satire. I’m doing it with Keith Carradine. It’s for cable.

SISCHY: Do you play a gangster?

STANTON: Yeah. I’m playing the first heavy I’ve played in a while. I’m playing a hit man.

SISCHY: Oh, but Harry, you don’t get shot again, do you?

STANTON: Do you think I get shot in every film?

SISCHY: No, but I really hated it when you died in Wild at Heart.

STANTON: Oh, yeah, I did die. I forgot about that.

SISCHY: Are a lot of people talking to you about Wild at Heart?

STANTON: I got an excellent response. I’ve never really been trashed by a critic yet, knock on wood. I’ve been ignored a few times, but I’ve been lucky most of the time.

SISCHY: Speaking about being lucky, do you feel lucky about your time as an actor?

STANTON: I’m very fortunate. I don’t think anyone should have a job that they don’t really enjoy.

SISCHY: Have your feelings about being an actor changed since you began?

STANTON: I change every day. I’m still changing.

SISCHY: When we first met you talked a lot about how important it was to you, as an actor, to be involved with other issues, like politics.

STANTON: Well, I’ve always been a searcher, you know, a hunter. I’m certainly not the only one. They say actors shouldn’t get political and everything, but you can’t separate yourself. You can’t disconnect yourself from anything.

SISCHY: I want to thank you, by the way, for showing me that letter from Chief Seattle. We published it in our Thanksgiving issue.

STANTON: That letter covers so much about the environment and a philosophy of life. It says a lot about the Native American experience and their knowledge—almost 150 years ago, in this case—about the importance of conservation and preservation. It was very prophetic. Sixty percent of the vegetables you see in the supermarkets came from the American Indians. They also gave us aspirin and quinine. And their model of government parallels our Senate. But their women elected the chiefs, and impeached them.

SISCHY: That was smart of them. Harry, what made you want to be an actor?

STANTON: I was in a speech class in college, and I had an ear for dialect. A community-theater director connected to the school put me in Pygmalion. His name was Wally Briggs. It just all sort of unfolded from there.

SISCHY: What was the first big part you had?

STANTON: The first major mainstream film I did was a picture with Alan Ladd and his son. It was called The Proud Rebel.

SISCHY: Good title for you. Are you content with your decision to become an actor?

STANTON: Well, I realized early on that if I became an actor, I could play a writer and a sculptor and a painter and be all the things you just don’t have time to be in your lifetime. I could get to learn about all of them.

SISCHY: Did you go to the movies when you were a kid?

STANTON: Yes. I walked out of the theater believing I was Humphrey Bogart. The first movie I ever remember seeing was She Married Her Boss. Talk about dating me, huh?

SISCHY: Can you remember what you felt, seeing a movie for the first time?

STANTON: All I remember about it was a little girl singing, “I don’t want to go to bed. I’m having too much fun.”

SISCHY: Have you been on a lot of TV?

STANTON: Only in the ’60s, when I first started. I think I did about fourteen Gunsmoke‘s over a period of seven or eight years.

SISCHY: I think Westerns are going to come back.

STANTON: Well, it would be great to have some that are truthful. I’ve never seen a Western that was really truthful. Most are just morality plays. Good guys and bad guys—and the good guys always win, whereas in reality most of the sheriffs were as bad as the gangsters they were after.

SISCHY: Did you ever play a sheriff?

STANTON: Yeah, I played FBI men, sheriffs, homicide detectives. They liked to put me in as a cop or a bad guy. Antagonists, as it were. But these days I rarely do television, unless it’s something very special. For a creative medium, it’s generally too rushed and censored. And broken up with usually odious commercials. It’s better now than it used to be, but it’s still repressive. I think David Lynch has done a lot to give it a shot in the arm.

SISCHY: It seems to me that you’re someone who’s very much in control of your life. You spend your day in the way you want to spend it.

STANTON: Yeah, doing nothing.

SISCHY: You play golf.

STANTON: I’ve been playing with Jack Nicholson at a nine-hole course in the Valley.

SISCHY: Are you any good?

STANTON: I’ve got a knack for it.

SISCHY: How did you get started playing golf?

STANTON: Well, actually, I was in a movie called Twister, and in it I had to hit a golf ball off of a roof with a driving wood. The guy who owned the place where we shot showed me how to do it, and I hit the ball about 150 yards.

SISCHY: Would you say that a lot of what you ended up doing are things you first experienced while playing parts in movies—like golf, for instance?

STANTON: Yes. That’s when I first rode a motorcycle. And I learned how to ride horses in movies too.

SISCHY: What about cards? I picture you playing cards.

STANTON: I used to play poker with John Huston, but I haven’t played much since he died.

SISCHY: When a person’s such a giant, sometimes it’s really hard to know how much you care about them. They’re almost overwhelming.

STANTON: We were both shy. We never sat down and had a long, one-on-one talk. I had an opportunity once, when everybody had left and I was the last one out and he sort of turned around—he was watching television, a football game—and looked like he wanted me to stay. It made me pretty sad after he died: I had had my opportunity to sit down and talk with him. Like I say, we were both shy. But we spent a lot of time at that poker table. We had our own special relationship. And I’m close to all of his kids. Anjelica, Danny, and Tony.

SISCHY: A lot of people talk about you as a musician as well as an actor. And a lot of people don’t know that you play music.

STANTON: I’ve always been a singer. I sang in high school, glee clubs; I was a soloist. Ry Cooder’s the one who got me singing as an adult. I’ve played all over the country, and recently I went to Australia and did clubs there with my band.

SISCHY: Do you play with one particular band?

STANTON: I play with two or three. I play with The Call. I played with Yvonne Hill. I’ve sung with Bob Dylan, just informally. And with Ry Cooder’s band and Kris Kristofferson’s. Lately I’ve been playing with a young guitarist named Jimmy Intveld, and Billy Swan, who wrote “I Can Help.” Billy’s one of my good friends. He and Kris Kristofferson, Rebecca de Mornay, Ed Begley Jr., and Jack. And recently Willie Nelson and I have had some long talks. He’s a great guy. There are dozens more people who mean so much to me.

SISCHY: Harry, when I came to your house I remember smiling at your doormat, but I can’t remember what it said.

STANTON: “Welcome UFOs and Crews.” Billy gave me that, actually.

SISCHY: You also had great stuff stuck on your refrigerator door. A baby photo among it all.

STANTON: That’s Dave Stewart and Siobhan Fahley’s baby. Dave Stewart of the Eurythmics. And Siobhan’s in her own band, called Shakespears Sister.

SISCHY: Rei Kawakubo from Comme des Garçons said it was great to have you in her fashion show. Was it fun?

STANTON: I really enjoyed it. She’s a real artist.

SISCHY: Lots of models nowadays want to be actors, you know.

STANTON: Well, modeling should be a performing art.

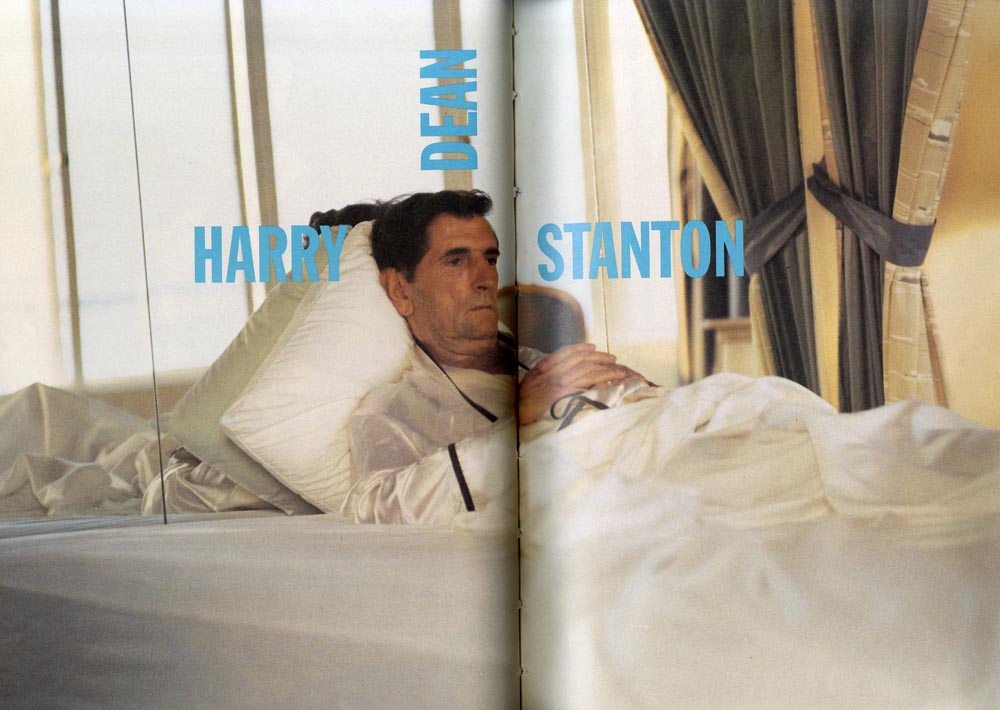

SISCHY: I can picture you right now in your hotel room—I picture you lying down. Are you?

STANTON: I’m propped up on the bed.

SISCHY: Have you been in most of the afternoon?

STANTON: I’ve been in all day, as a matter of fact. I didn’t have work.

SISCHY: Have you left the room at all?

STANTON: I went to the lobby and picked up a book from [sic.] Tim Young. He’s John Savage’s brother.

SISCHY: What’s the book?

STANTON: It’s called Living. It’s a distillation of [Jiddu] Krishnamurti’s teachings, compiled by J.C. van Rijn. Buddhism and Taoism have both had a big influence on my life. Let me read you something from another book I have here. It’s called Cloud-hidden, Whereabouts Unknown: A Mountain Journal, by Alan Watts: “How many of us now realize that space is the same thing as mind, or consciousness? That when you look out into infinity you are looking at yourself? That your inside goes with your entire outside as your front with your back? That this galaxy, and all other galaxies, are just as much you as your heart or your brain? That your coming and going, your waking and sleeping, your birth and your death, are exactly the same kind of rhythmic phenomena as the stars and their surrounding darkness? To be afraid of life is to be afraid of yourself.”

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY RAN IN THE JANUARY 1991 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.