Lightening Strikes Matt Porterfield

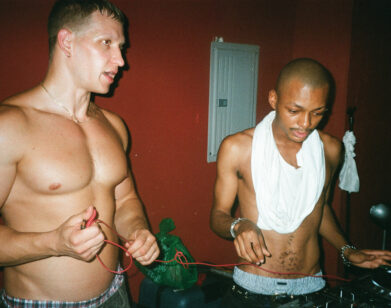

ABOVE: MATT PORTERFIELD. PHOTO BY DEENAH VOLLMER

Matt Porterfield’s films are quiet and patient, suggesting more than they tell. They’re characterized by long shots, handheld cameras, casts of non-actors, and sound coming almost entirely from inside the world of the characters, sometimes music that is played or heard on the radio, or more often the buzzes of ambient noise that become loud when the microphone picks them up. Filmed in Baltimore neighborhoods, they occur over the course of a day or two, shot almost entirely in houses and backyards, and focus on a small community of people whose lives are affected and entangled by a commonplace drama: a birth (Hamilton), a death (Putty Hill), a divorce (I Used to Be Darker).

The most recent title reads like a commentary on the other two, the literally and figuratively least dark of the three. Porterfield is so committed to the phrase, the sentiment, the order of the words, or all three that he’s tattooed the sentence onto his forearm. It comes from a lyric by Bill Callahan, the singer from Smog and another Maryland native whose unhurried songwriting shares much in common with the filmmaker’s sensibility, which can be generalized as sad, but hopeful. I Used to Be Darker is about two musicians, one working and one who used to, who struggle to end their marriage harmoniously while their college-age daughter (Hannah Gross) and their Irish runaway niece (Deragh Campbell) add their own troubles to the mix.

The male lead was called Bill on the off chance Callahan wanted to play the part himself. He didn’t, but not at an expense to the film. Musicians Kim Taylor and Ned Oldham were superb choices and their country-tinged folk rock music guides the narrative and, at the same time, allows an emotional release for both the characters and the audience. Porterfield spoke to Interview at the Berlin Film Festival this February.

DEENAH VOLLMER: Tell me about how you chose the title of your latest film.

MATTHEW PORTERFIELD: I felt like the lyrics “I used to be darker, but then I got lighter, but then I got dark again. Something too big to be seen was passing over and over me,” expressed a way to see the world, how we pass through it in various shades. It was a sentiment I could connect with and one I felt any one of the four main characters could have expressed in the past, present, or future time. This darkness is something that is both transitional and certain to return. It had relevance for me, for the characters. It’s a great title.

VOLLMER: It is! Why did you choose to make a film that focused so heavily on music and musicians?

PORTERFIELD: I’m not a musician, I can’t carry a tune, and maybe I don’t have a direct relationship to music more than anyone else. It’s always been important in my life. My co-writer Amy Belk and I knew that these characters, the couple separating, they were artists trying to balance their responsibility as providers, parents, and partners with their creative aspirations and goals. Amy comes from a fiction writing background, and I’ve been a struggling filmmaker for years. That seemed like something we could write about. We thought about the music that informed the story. Amy knew Kim Taylor. I knew Ned Oldham. Suddenly we had these two characters who were both working musicians at the time.

VOLLMER: Which came first, the songs or the story? How did you integrate them?

PORTERFIELD: It was pretty organic. The songs were integral. The two songs that that Kim performs, “American Child” and “Days Like This,” were both in the original screenplay. We knew when they would play in the film. We wanted Ned to sing something and smash his guitar. He brought the song to us. He had written it with his band, but it had emotional and narrative relevance to the story. The other song that Ned sings was inspired by a poem my dad had written in the ’60s, from a collection of poetry called Love and Hepatitis. I asked him to adapt it, and he did.

VOLLMER: Why did you choose musicians and not actors?

PORTERFIELD: I’ve made it a priority to work with actors who were new to the screen. I wanted to continue that mode of casting. I had worked with a couple musicians on Putty Hill, Sky Ferreira most notably. Musicians have an understanding of what’s involved in performance, a sense of their body, their voice. They bring a level of professionalism, even if they’ve never acted before.

VOLLMER: What appeals to you about non-actors?

PORTERFIELD: I’m interested in cinematic realism. I think there is a rich potential to bring to audiences people they haven’t seen before, that they are discovering a bit like how we discover people in life for the first time. There’s an authenticity that can’t be denied.

VOLLMER: Ned and Kim sometimes perform together to celebrate and promote the film. Is it surreal for you to have the film come alive in this way?

PORTERFIELD: It’s incredible. Ned and Kim perform a song together, which is not in the movie, their version of “Love Hurts,” it’s a heartbreaker. I get really excited when I think about audiences discovering the four principal actors for different reasons. If audiences walk away humming these songs and looking Ned and Kim up on the Internet and trying to find their music… their music should be part of popular culture. If this film does any small part in achieving that, I feel really pleased.

VOLLMER: Baltimore is very strongly represented on screen. How do you see you own work next to that of Barry Levinson, John Waters, and The Wire?

PORTERFIELD: I think it’s interesting that these seminal visions of Baltimore on screen are all focused on the American middle class in particular. It’s true of my films too. What is it about this place? I don’t know. I think it provides a rich template. If you look at the distinctions, it all kind of breaks down to the neighborhoods in which we choose to set our films. Baltimore is called the city of neighborhoods because it’s very compartmentalized and divided along race and class and stuff like this.

VOLLMER: What’s it like to make films in Baltimore?

PORTERFIELD: The city holds a lot of mystery for me still, despite the fact I’ve lived there most of my life. I think its shares a lot of issues and dominant themes with other second-tier post-industrial cities in the U.S. It has a universal resonance. I’m close to NY. That’s the industry bastion for me. I like being outside it, but still having access to it. There’s a way you maintain an autonomy working outside the great industry hubs. It’s easier to greenlight your own films when you’re not surrounded by other people aspiring to make films. You have to work a little harder and rely more on yourself and your collaborators and the real relationships you have. There are so many hypotheticals that dominate the industry, and everyone’s always waiting for someone else to tell them when to make a film and write a check and sign the talent. Those aren’t realities the way I make films in Baltimore.

VOLLMER: You teach film at Johns Hopkins. How has teaching change the way you think about film?

PORTERFIELD: It feeds me intellectually, teaching students about film, a way in which it serves the whole. I like being connected to young people, or younger people who are trying to figure out the language of film, bringing theorists from the dawn of the art in the 20th century. There is a way you find a synthesis. You read texts by the Soviets who are discussing montage, and you have students figuring out how to put scenes together and tell stories visually. The theory becomes relevant in daily practice. It’s free labor, which is pretty cool too. [laughs] They can fulfill internships or independent study requirements. I think we all learn from each other and benefit from the collaborations.

VOLLMER: Do you find that teaching and filmmaking have a lot in common?

PORTERFIELD: I learn more about how to run a set teaching six-year-olds. You go into a classroom as a teacher, and the most important work you do is create an infrastructure and an environment that’s safe, in which children will feel able and free to take risk. Working with actors, you have to establish the same thing. Teaching a class is not so different than mounting a production.

VOLLMER: What are your plans for the next film?

PORTERFIELD: I’m trying to get a little more personal with each film. Each of my films is personal. Maybe the distance between me and the subject and the camera and the subject is closing. This next film is about a guy on house arrest, my age, he’s an ex-offender. I’m not. He’s living with is dad, which I’ve done. I’m interested in the infinite narratives that could play out for each of us, what choices have I made that find me here, but could have done it just a little differently and I could be on house arrest. Not much of a stretch actually.

VOLLMER: Tell me about the dollar sign tattoo on your middle finger.

PORTERFIELD: It’s both an acceptance of the fact that the work I do is part of a particular economy and has to be recognized, and its also a fuck-you to the dollar. All of my tattoos are about balance.

I USED TO BE DARKER OPENS AT IFC IN NEW YORK ON FRIDAY, OCTOBER 4. NED OLDHAM’S BAND THE ANOMOANON PERFORMS ON SATURDAY, OCTOBER 5, WITH GUEST APPEARANCES BY KIM TAYLOR; AND TAYLOR AND OLDHAM BOTH PERFORM AT THE LIVING ROOM ON SUNDAY, OCTOBER 5.