Filming Robert Frank

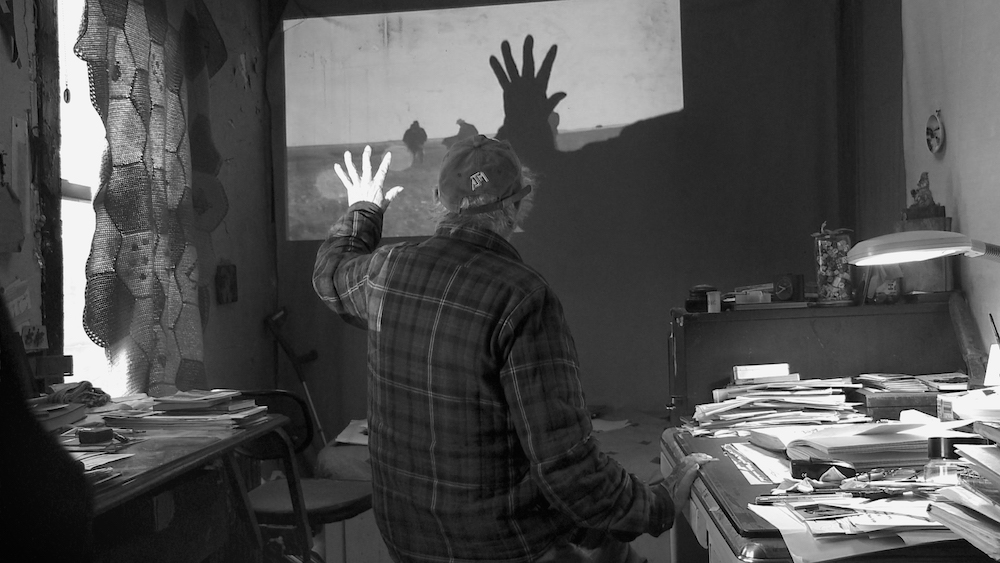

ROBERT FRANK IN DON’T BLINK – ROBERT FRANK, DIRECTED BY LAURA ISRAEL. PHOTO BY LISA RINZLER. COURTESY OF GRASSHOPPER FILM.

In addition to his prolific, life-long output of transcendent images, we have to thank Robert Frank for The Americans. When the Swiss-born artist, now 91, published the book of photographs in 1958, accompanied by an introductory text by Jack Kerouac, the series of stark, black-and-white images of cowboys, factory workers, lunch counters, and trolley cars served as not just a coast-to-coast ethnographic survey of the country, post-war, but as an illuminating mirror of the nation’s id, and cemented Frank as the medium’s new bard.

Filmmaker Laura Israel, Frank’s longtime editor, likens this seminal work to a door which allowed Frank to pursue his art practice in whichever meandering way it took him: moving image (Pull My Daisy, 1959; Candy Mountain, 1987), documentary (the infamous Rolling Stones tour doc Cocksucker Blues, 1972), video, and collage. The pair met in the late ’80s, when Frank directed New Order’s “Run” music video and Israel was the editor assigned. It was their decades-long friendship that Israel credits to opening up the famously press-averse artist to agreeing to be filmed for her second feature documentary, Don’t Blink – Robert Frank, a textured account of the artist’s life and work, even if the two were both skeptical about it at first.

Interview spoke with Israel last week in New York in advance of the film’s opening, tomorrow.

COLLEEN KELSEY: When did you first encounter Robert’s work?

LAURA ISRAEL: A lot of people don’t know that the first job I ever did with him was for New Order for a song called “Run.” I used to edit a lot of the New Order videos. My friend Michael Shamberg was part of Factory Records. He’d done something with Bill Wegman for “Blue Monday,” and then he said, “I’m gonna pair you with Robert Frank.” I went, “Oh cool, that’s great,” because I loved him. The very first day he came to my studio, we used to do the selects and because it was tape, we’d have to rewind the tape, fast forward the tape, all that stuff. I turned around to him, because I didn’t really know him, and I said, “Well, if we make these selects, you’re gonna wanna go back and do it again.” He goes, “No. We only go forward. It’s fate. We never go back. First thought, best thought.” And I thought, “This is my kind of director.”

I lived on 4th Street at Avenue A, and my studio was on Broadway and Bleecker Street, so I used to walk by Robert’s house and run into him. Then, I didn’t realize how into postcards he was, and I’m a big postcard collector. So every once in a while if I got a good postcard I would write him a little note and just slip it in the door slot as I walked by. I think that cemented the friendship. Then he worked on something that was film, and I wasn’t really editing film at the time. I only had video equipment, so I found him somebody who worked with John Sayles. We continued the relationship and we became friends, really. Which is a whole other way of working. I couldn’t picture him working with anybody he wasn’t friendly with. It was a different way for me, because I would get called up and do jobs, and then you wouldn’t necessarily connect with the person or be friends with them, and then they’d call you again because you did a good job. But this was a whole different thing. He gave me all his books, sometimes we just went to lunch. I really enjoyed that about him.

KELSEY: So how did this documentary come about?

ISRAEL: Well this was totally a fluke. I went to IDFA—International Documentary Festival in Amsterdam—with my first film, Windfall. There was a writer there—it was like a mentoring program, you could speak to anybody here on this list. On the list was a writer named Tue Steen Muller who writes about Godard, Chris Marker, and Agnès Varda as documentary filmmakers. So I thought, “Hey, if there’s anybody I would connect with it would be him.” I brought a little card of Windfall and I was like, “This is my film in the festival,” and he kind of tossed it and went, “Ugh, we have lots of windmills around here and I think this film is crap. I think you have a lot of nerve doing a film about this.” I was really intimidated because he’s like this older gruff guy. [laughs] And I was like, “Oh because I work with Robert Frank, I thought we would have something in common.” He lunged over the table at me and he’s like, “That’s your next film! You want my advice? That’s what you’re doing a film about. You know how many people I know who can’t even get him on the phone? He won’t even give them the time of day!” All this stuff. He’s pounding on the table and I was like, “No, it would be really weird.”

I’m his editor, turning it around and having him be the subject would be really odd for me. So I got on the plane, and I’m looking out the window and imagining some scenes that I would shoot, and one of them ended up being in the film. That was the scene in the car driving around with Tom Jarmusch taking photos. I thought, maybe it would be interesting to do this as my next project. I said to Robert—first day I got back I went to see him—and I said, “Do you think it’d be a good idea for me to do a film about you?” and he was like, “No, that would be really weird.” He said the same thing as me. So I changed the subject really quickly, and there were other people there and stuff but I can tell he’s kind of looking at me out of the side of his eye. Then he was like, “You come back tomorrow and we’ll talk about it. I think that might be a good idea. We’ll talk about it tomorrow.” I came back the next day and he said, “Let’s start next week.”

I was kind of thrown into it. I did that whole year of festivals and also started shooting and trying to fundraise for the film I was doing with Robert. Luckily Lisa Rinzler sent me an e-mail. She’s the DP in the film. She sent an email the next day or something saying, “Oh, I’m so excited! I showed Robert Frank my photos and he really liked them.” Then Ed Lachman came later, because I was working with him on a different project. I knew he was friends with Robert, so I was like, “Oh, maybe we’ll go take a trip up to Nova Scotia,” and Lisa…the way she shot, she was very conscious of lighting, everything was really perfect—that black-and-white footage in the film. And Ed Lachman’s like, “I’m just gonna put it on a tripod and we’ll just talk about stuff.” I thought it was great that there’s two complete opposite ways of looking. I feel like Robert has those two different elements about him.

KELSEY: Definitely. The film is so layered in terms of its materials, and you started shooting pretty quickly after he said yes to the idea. How did you go about conceptually organizing, not just the structure of the film, but the themes that you wanted to explore?

ISRAEL: Any time I got confused, I went back to Robert’s work. He often would do films and videos about whatever theme he was exploring, and whatever theme he was exploring at the time reflected what was going on in his life. At one point, he sent me all this stuff about “The Old Snapper.” He used to sit in Mabou [in Nova Scotia] and look out the window and he had a typewriter and he called himself “The Old Snapper” as a persona. Then I realized there were all these photos of the Old Snapper, the Old Snapper appeared all these different ways in the writing and the letters that he sent and stuff. It was difficult to figure out how we would travel. It would go to his life, then go a little bit to a photograph, and then maybe this part would be represented best by a film. We tried to change it up, because I find that quite often films about photographers are just so still. And so we were lucky that we also had a filmmaker.

I wanted to show The Americans, and the Stones, and Pull My Daisy almost as a door that opens into some of the other work, because I think he’s been pretty prolific. As I was telling somebody, he’s been really good at being famously unfamous. [laughs] It creates a longevity for him, I think, as an artist. But also I think it made his life a lot more manageable. I really enjoy a lot of the personal videos and I would be really happy if this film could help other people discover them. And the Polaroids, I think, are fantastic. Some of my favorites are the scratching on photographs with words and stuff in the ’80s and ’90s. So I’m happy if that work can do that for him. I think he realizes that. I think he said more than once that, “The Americans really enabled me to do everything I did afterwards.” I don’t want to speak for him, but in my opinion, he has a conflicted idea about fame. Because on one hand it did help him, but on the other hand, with a lot of what happened in his life, he tries not to be in the limelight.

KELSEY: How did you find that your background in editing affected the structure of the documentary?

ISRAEL: Well, I was so happy to work with an editor. That is one thing I would recommend to everyone and every filmmaker in the world, it’s to have an editor. [laughs] Because it really helps. As Robert said, “Four eyes are better than two.” You can turn around and say, “Am I crazy or is this great?” Beause there’s a fine line between fantastic and really horrible. [laughs] Or a big mess and something brilliant. It’s a big mess right before it gets really good. But I find being an editor helps a lot in interviews because quite often the DP would be saying, “Oh, they didn’t say that right,” or something, and I’ll go, “Don’t worry about it, we don’t need that part.”

KELSEY: Because you’ve already figured it out, in the cut. [laughs]

ISRAEL: I’ve already figured it out. There was one time where the DP actually was insisting and I was like, “No, no, no, no, no—I’ve already heard what I need.” So I think that as an editor that really helps a lot.

KELSEY: Right.

ISRAEL: The other thing too is I’ve learned from so many other directors that I’ve worked with—fantastic directors—by seeing all their outtakes and what works for them. I realize that it’s really bad to know what you want when you go in and just look for those sound bites. It’s always the story that you don’t know about or that’s underlying… When you say layer, that’s sort of what I think Robert’s about—this sort of encryption, almost. That’s what we found out when we started to really do the intensive research.

We had to decode a lot of his work and try to give context that we knew people would understand. He purposely makes it mysterious because it makes it more interesting. I think it’s just in his nature, actually, to make it more mysterious. There’s an interesting quote that I’m so amazed that Errol Morris gave me for the film. He said that, “Maybe films about photography provide too much context and that’s what ruins it.” But in this film I tried not to give too much context. I try to ride that line between giving too much information and keeping it a little more mysterious. It’s interesting, working with him all that time, doing this documentary is the most I’ve had conversations with him. Usually we talk about the weather, we talk about the footage, we never really talked about his life in depth or his thoughts.

KELSEY: Was he forthcoming about that? Or not so much?

ISRAEL: He was, but, I think it’s because, first of all, I told him we were going to have a really small crew. It’s funny because he said, “That’s a really smart idea.” Then I read somewhere that that’s what he told the Rolling Stones when he shot Cocksucker Blues, and they would only bring Danny Seymour with them, and that’s why they agreed to let him do it. The other thing that helped is I started to realize after I got the initial interviews that I should bring a friend along, or there should be more of a conversation. I’m not just sticking the camera in his face. It’s not an interview, it’s more like we’re all just hanging out. And one point too, [Frank’s wife] June [Leaf] says that. We were shooting for an hour and she goes “Oh, are you shooting?” And we’re like, “Yeah, we’re shooting” and she’s like, “Oh! I just thought this was a friendly hangout.” [laughs]

DON’T BLINK – ROBERT FRANK OPENS TOMORROW AT FILM FORUM. FRANK’S COCKSUCKER BLUES WILL SCREEN AT FILM FORUM JULY 20 AND 21.