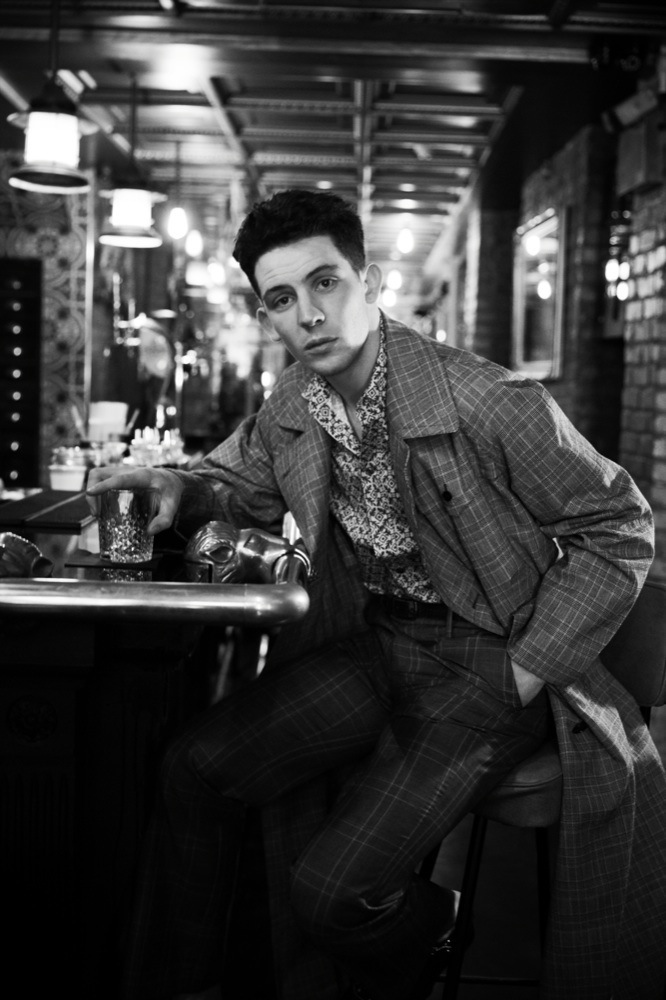

Josh O’Connor

PHOTOS: MATT HOLYOAK/KAYTE ELLIS AGENCY. STYLING: NIC JOTTKANDT. GROOMING: NINA BECKET/CAROL HAYES MANAGEMENT. PHOTO ASSISTANT: BEN COLSON. SPECIAL THANKS: MAP MAISON. RETOUCHING: THE SHOEMAKER’S ELVES LONDON.

When we first encounter Johnny Saxby, the protagonist of actor-turned-writer-director Francis Lee‘s first feature God’s Own Country, everything about his lifestyle is bleak and oppressive. From the early morning to sunset, he struggles to maintain his family’s failing farm, trudging through the mud and birthing livestock. At night, he gets blackout drunk at the local pub, vomits, and passes out before reaching his bed. His only interactions with other humans are curt, practical exchanges with his grandmother; arguments with his wheelchair-bound father; and transactional sex in bathrooms and trailers with near-anonymous men. It is a Sisyphean cycle that is reflected in everything around him—even the landscape, the Yorkshire countryside that is so often portrayed as idyllic, is grey and broken. Then, Johnny meets Gheorghe (Alec Secareanu), a Romanian immigrant who has agreed to spend a week working on the Saxby farm, and what you expect to be a devastating slog of a film develops into a beautiful, optimistic, tender love story.

Shortly after the film’s premiere at Sundance in January, we sat down with Josh O’Connor, who plays Johnny. Originally from Cheltenham, England, O’Connor studied acting at the Bristol Old Vic Theatre School. God’s Own Country is not the young actor’s first powerful British indie film. In 2015, he starred opposite his then-girlfriend Hannah Murray in Bridgend, Danish filmmaker Jeppe Rønde’s incredibly dark, fictional portrayal of a real town in Wales with an alarmingly high teen suicide rate. O’Connor also appeared alongside Sam Claflin, Douglas Booth, Max Irons, Freddie Fox, Ben Schnetzer, Olly Alexander, and Matthew Beard in The Riot Club, Lone Scherfig‘s adaptation of Laura Wade’s play about class and privilege, Posh, and, more recently, Florence Foster Jenkins with Meryl Streep and Hugh Grant.

EMMA BROWN: Harris [Dickinson] from Beach Rats said he also auditioned for God’s Own Country.

JOSH O’CONNOR: Yeah, it’s become an in-joke, because Harris is beautiful and very good, and Francis keeps being like, “I wish Harris had done the film.” He’s really great, Harris. I met him only at this festival, but he’s wicked. You were at the premiere, right?

BROWN: Yes.

O’CONNOR: The premiere was horrific.

BROWN: What makes you say that?

O’CONNOR: I think we were just really nervous and people were walking out during the sex scenes.

BROWN: My friend and I were making fun of those people. It got so much more uplifting.

I loved what Francis said at the premiere about how people work so hard in that part of England, that as long as you do your work, no one cares who you sleep with.

O’CONNOR: It’s so true. The character that I play in the film, everything we did, he’s arched over and we had his hood up a lot, which was quite like Bridgend, weirdly. Everything is about the work; they don’t ever look up. What’s cool about Francis’s film is that there’s one moment when we actually look at the landscape. There’s one landscape shot sort of halfway through the film. And it’s the first time he looks up. The sexuality, his whole lifestyle—allowing love into his life—there’s no time. It’s just brutal. I really liked Francis’s idea about that as well. He speaks really well.

BROWN: Can you tell me a little bit about how you got involved with it? Was it a normal auditioning process?

O’CONNOR: My friend was auditioning for it. I remember I had him over for dinner and he was like, “I’ve met this amazing director and the script is insane. I feel like this is the script for me.” I was like, “Okay, sounds like the script for me,” so I called my agent and they sent it through. I read it, and I was completely in love with it. Then me and Francis went for lunch. The first time was just talking about it, and the second time I think I did read some scenes. Then we discussed if I was to do it, how I’d want to. I was very specific about wanting to be method, which I haven’t really done before. I wanted to try it out. Everything needed to be so vivid, because the script was so detailed. It was unbelievable. Francis had such a clear image of what the character needed to be.

BROWN: Is your family creative?

O’CONNOR: Creative, yes, but no actors. My dad’s an English teacher and my mum’s a midwife. Then my mum’s side of the family are all crazy creative. My grandfather was a brilliant sculptor. My aunt wrote for The Guardian and is now a fiction writer. My brother’s an artist. My grandma is a ceramicist. I wanted to be an artist; it was be an artist or be an actor. This seems to be working right now.

BROWN: Is your brother older or younger?

O’CONNOR: I’ve got two brothers. One’s older—the artist—and then my younger brother is an ecological economist—a farmer. He looks at localized economies: how we can be sustainable and sustain wealth and redistribute wealth. He’s a massive lefty, like all of us. I have the best family in the world.

BROWN: Did you get along when you were growing up?

O’CONNOR: We fought a lot. Weirdly it was that my little brother would set off an argument between me and my older brother, and then we’d trace it back: “Why did we argue? What was the root?” We’d realize it was Seb, and Seb would be gone, off on his own hanging out with my mum being cool. Now we’re best friends. I don’t see them enough.

BROWN: What made you want to go to drama school?

O’CONNOR: I love theater and I really wanted to do more theater. That was the initial thing. Film has been kind of late for me; I now am a super film buff. It’s still theater and film. I haven’t got a huge interest in doing television.

BROWN: But you were on Peaky Blinders.

O’CONNOR: I was on Peaky Blinders, which is a good show. I could do Peaky again. Also I do the show The Durrells, and it’s great and it pays for my life. I do like it. But I think film—not all film, but the kind of films I’ve been doing recently like this and Bridgend—they’re the best experiences I’ve ever had and I wouldn’t want to change that.

BROWN: Did you end up going method for God’s Own Country?

O’CONNOR: Pretty much. I lost a stone and a half and then I worked on this farm. I had this book, kind of a scrapbook, which I do for every role anyway just for fun. When I first met Francis and he first offered me the part, he showed me this book he’d done, which had bits of material and a smell he’d rubbed off on the page of the area, or a photograph that he liked of farming lifestyle. It was an incredible book of sensory information. So I did my own thing; I had my own book of senses—paintings and drawings that I’d done and ideas I had. From there, I worked physically with Francis about how this guy would look. By the end of the film I was so skinny; I was gaunt. It was horrific. I was in character the whole way through. It was really lonely and hard. I don’t think I’d do it again. You isolate yourself from all your friends.

BROWN: How long was filming?

O’CONNOR: Six weeks. By week four we had to stop filming because I was so sick. I was in the hospital on a drip. It was an infection. I lost another stone and a half—I was three-stone down by the end by the end of the film. I think it was exhaustion. I worked very hard, and so did Francis, and there were days where I didn’t wash my hands. This farmer I worked with wouldn’t wash his hands. He’d get up at 4 A.M., feed the sheep, and come back and have this disgusting white bread and egg and bacon sandwich. I was really interested in the lack of care he had for himself. His world didn’t exist beyond the fields that he lives in and, emotionally, he had no kind of lifestyle really. It was almost self-inflicted damage. Abusive. So I imagine it’s probably because I didn’t wash my hands. [laughs] I got very ill.

BROWN: Did you and Francis discuss where your character goes after the film ends?

O’CONNOR: No. I have my own theory. I hope that they maybe have a summer on that farm together. I actually think it’s better they’re not together for the rest of their lives. I think it’s a really cool snapshot.

BROWN: Everything happens so quickly. It’s easy to forget that Gheorghe’s just been there for a week. Part of me was like, “I hope they get married and redo the farm!” But actually it’s very early days. [laughs]

O’CONNOR: Yeah, it’s really early days. They have a great connection. Johnny opens up at the end, [and] I think that’s a really exciting thing for him and probably he’d want to explore that with other people. It’s the first time he’s ever opened up emotionally. Certainly with me, I don’t think I’m very open and I think if I had that moment of, “Oh my god this is really great, to be really open and be loved and be in love,” you’d want to go and experience that.

BROWN: With a lot of people?

O’CONNOR: With a lot of people. Not necessarily like Johnny does [at the beginning]; Johnny sleeps with people when he needs to. He fucks people. But I think that’s a different thing—that was an abusive, self-destructive act. And almost a necessity. It was like going to get your groceries—you go and fuck a guy in a cow trailer. It’s not loving at all. Whereas I think that probably after the film ends, he’s experiencing that love, which is really cool and exciting. I hope so. [But] he doesn’t exist. He’s not real, so it doesn’t matter.

BROWN: Were you and Alec cast simultaneously? Did you have chemistry reads or anything like that?

O’CONNOR: I did have chemistry reads with four Romanian actors. There are some really great Romanian films. The four guys I met for that film were so freaking amazing and Alec was incredible and just perfect for it. I think we both, me and Francis, liked the idea of a really beautiful, solid man coming into this ugly, unstructured world, and Alec had that in abundance. In real, life he’s the most chill. I’m the most frenetic and scary person and he’s the most calm.

BROWN: It’s such a small cast, and if you were method, what was that like on set? Did you and Alec talk to each other?

O’CONNOR: It was actually really difficult. At one stage, me and Francis really wanted me and Alec not to meet until we meet [in the film]. That became really difficult, because we had to rehearse the sex scenes, so that didn’t happen. I was in character on set, [but] me and Alec lived together on Francis’ dad’s farm, so it got to the stage where we had to talk. In the evenings, I would talk in a Yorkshire accent, but I’d be like, “I miss my girlfriend.” [laughs] We got on very well. It’s weird now being at Sundance together promoting the film, and me talking in a normal accent. It just doesn’t seem right at all. There’s literally no trace of me in Johnny, which is quite cool. I love that. Actors never get that chance, really, to play something that’s so far removed from them. I think Bridgend is closer, that’s more of me … Bridgend was a really traumatic experience for me and for Hannah [Murrary], and I think for everyone involved in it.

BROWN: Because it was so dark?

O’CONNOR: So dark and Jeppe Rønde is fucking crazy. When I came to Denmark, it was the first time I’d seen the film and we went to this premiere in Copenhagen. It was the most insane cinema. I think it’s the biggest cinema in Europe—massive—and it was sold out. People were so excited about the movie and it did really well in Denmark. Lone [Scherfig] was with me; she came and she was on my right, and on my left was this guy who was shaking and breathing really heavily as the film was playing. I was shit-scared, because I was watching me and my ex-girlfriend fall in love on screen, then trying to kill myself and her dying. It was just horrific and a really powerful movie. And this guy was making these horrible noises. At the end of the film, everyone gave a standing ovation, and this guy just sat down. Lone said, “Come on, Lars.” And it was Lars von Trier. Lone said to him, “Did you enjoy the film, Lars?” And he was like, “Yes.” And he took me by the arm and said, “It touched my heart. It touched my soul, but it’s totally immoral.” I was like, “That’s Lars von Trier saying that? This film is not going to get released.” What a funny thing. He was amazing.

BROWN: That’s terrifying.

O’CONNOR: What a cool and terrifying compliment from Lars von Trier. [laughs] Then Lone took me out for dinner and I broke down in tears. I never cry and I gushed with Lone. She’s like a parental figure to me and she just has this incredible power to unleash emotion. She’s incredible. Big fan. I quite like that Lars von Trier story. I really want to work with him.

BROWN: Keep putting it out there.

O’CONNOR: Yeah, I’ll just keep reminding him.

BROWN: “I’ll do other immoral things…”

O’CONNOR: “I can do other immoral things, Lars! Just get me in the room!” [laughs]

BROWN: Do you know what you’re doing after the Berlin Film Festival?

O’CONNOR: I’ve got a little bit of a break. I was going to direct a short film. I kind of want to get into directing as well, but not narratives—art films maybe. [But] that’s not going to happen for another year. I’ve got a film coming up that I’m attached to, that’s in April. Then I’ve got a third series of the The Durrells, which starts in May [and goes] through to September. It’s really cool to have stuff looking forward.

GOD’S OWN COUNTRY SCREENED AT THE BERLIN FILM FESTIVAL LAST MONTH. FOR MORE ON JOSH O’CONNOR, FOLLOW HIM ON TWITTER.