The Art of Being David Lynch

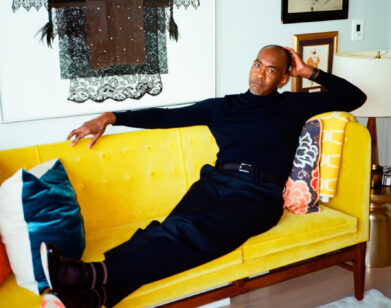

DAVID LYNCH IN DAVID LYNCH: THE ART LIFE, DIRECTED BY JON NGUYEN. COURTESY OF JANUS FILMS.

Many have tried to unravel the many mythic personae of David Lynch. But the notoriously private 71-year-old auteur of Freudian fever dreams Blue Velvet, Wild at Heart, and Mulholland Drive, who succinctly describes himself on his Twitter account as, “Born Missoula, MT. Eagle Scout,” defers analysis to the work itself. His artistic output has been deemed so iconoclastic to earn its own adjective: Lynchian. David Foster Wallace tried to approximate the term in a 1996 Premiere profile: “You don’t feel like you’re entering into any of the standard unspoken and/or unconscious contracts you normally enter into with other kinds of movies.” Lynch’s thematic preoccupation with sex, darkness, and danger, all swaddled in the pristine care package of the American Dream, begs the question of what, exactly, are the motivations of the man behind the lens, a man whose love of small town Americana, coffee, and doughnuts charmingly obscures his inner creative impulses.

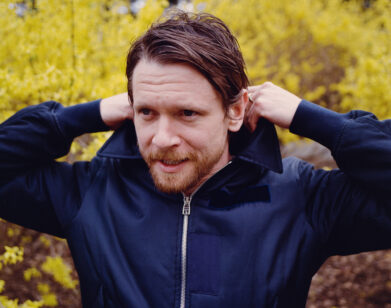

A new documentary, David Lynch: The Art Life, seeks to answer that question. After producing the 2007 documentary Lynch, a fly-on-the-wall account of the making of Lynch’s 2006 film Inland Empire, Jon Nguyen set out to complete a companion piece on the director. Crafted over the course of four years, Nguyen puts the Los Angeles-based painter-turned-filmmaker under observation as he works in his home-cum-studio in the Hollywood Hills. Lynch’s current creative output: paintings, writing, music, are exhibited alongside interviews with the director, where he discusses his upbringing in the ’50s, embrace of painting, early animated film work in Philadelphia, and on through the creation of his first feature, Eraserhead. But Lynch as an enigma remains intact.

When asked if it was possible to get to the underbelly of Lynch’s creative psychology, Nguyen said, “I don’t know if anybody can get there.” Interview recently spoke to him in New York.

COLLEEN KELSEY: Before we get into the particulars of making the movie, I would love to hear a little bit about how you first became engaged with David Lynch and his work.

JON NGUYEN: I remember going with a friend of mine to watch Lost Highway when it was in theaters. It caught me off guard. I walked out completely confused and with so many questions, but fell in love with what was going on in my head. I had never seen a movie like that where my mind was just racing to piece things together afterwards. It felt more like an experience rather than just watching a film. A lot of cinema is kind of passive. For me, it was very active. I went back and discovered his earlier films. I had actually seen Blue Velvet, but I didn’t connect [it]. I had seen Elephant Man. Then later on I saw Eraserhead, which, of course, I fell in love with that one.

KELSEY: Lynch is a precursor to the path to the production of this documentary, but when did David personally come into your orbit?

NGUYEN: It was around Mulholland Drive. I was floored by that film, and it happened to be that one of my very good friends was one of David’s personal assistants on the production, so I called him up one day, just pitched, “Do me a favor, ask David if I can make a film about him.” My friend laughed. He said, “No way. David is never going to let you make a film about him. He’s very private,” and I was like, “Just ask him. I can deal with rejection.”

He called me up two or three days later and he was like, “You’re not going to believe it, David agreed to let you make a film about him,” and I was just like, “Can I get it in writing?” [laughs] So, that started the whole process. I remember in the beginning, I was a producer on that project. It was my idea to make the film, but I was a producer on that, so my friend who knew David directed it and even then when we sat down to interview David, he was just smoking a cigarette, not really open to being prodded and questioned. He was so funny. “Take your camera, follow me. You’ll know what the film is about by the end,” so that was a very cinema verité kind of film.

But at the end of that whole process, Jason [S., Nguyen’s collaborator and cinematographer] and I were like, “We get this feeling that he’s kind of warming up to us. Let’s wait a little bit and come back to him again when he gets a little bit older. I think he’s going to open up.” We waited and we waited and when he had his daughter Lula, we were like, “Okay, let’s pitch it to him then—David, you’re older, your daughter’s very young. When she becomes mature, you know, you might not be around. Here’s your chance to tell her your story.” He agreed. That was the entrance back in. At this time, we got to know him really well. He was very comfortable around us, so it was just the opposite. Instead of following him around, this time it was, “Let’s talk.” In two and a half years, we were only able to get 25 hours of conversations. Weeks would go by, sometimes months would go by, when David didn’t really want to, wasn’t available to talk, but we were still there and it was just whenever he felt in the mood, we would hear this little [makes buzzer noise] on the intercom, “Come on up. I have a half an hour.” Put on the thing, “Okay, today let’s talk about your mom,” which is a broad subject. “Tell us everything. Tell us anything.” It was just a doorway to get into stories. Other interviews would be like, “Okay, today we are going to focus on the ’50s. Tell us anything you want about your life in the ’50s.”

Using these broad strokes, we were able to give him a canvas to let these stories leak out, because we knew that was what we wanted to do. He’s always been reluctant to talk about his films. He’s very reserved. Talking about his films we were like, “Okay, the best key to understanding his films must be from him as a person.” And it’s not him as an adult, it’s him during formative periods. I wanted learn about him during Philadelphia. I was like, “Oh, there must be interesting stuff, because that’s when he was really formulating these ideas. Must be,” so we framed it that way up to Eraserhead. Once he becomes a filmmaker living in L.A. was not interesting because it was a different lifestyle. The early, young artist period, I knew was going to be interesting. Using that framework we were able to dig up stories to help us to really understand his films a lot better.

KELSEY: First of all, you have someone who is not very open to being interviewed. Coming from the very beginning did you have any goals of things to discover, or was it more about the excavating ideas?

NGUYEN: Excavating, because from past experience he can be very guarded. We’re not just journalists coming at him off the street. We’re people that he knows now, he jokes around with, he doesn’t hide stuff from necessarily. So, we knew that, and we were just like, “Now, he’s difficult to schedule, so, okay, we’re going to camp out here.” We couldn’t just live somewhere else and make trips into L.A. In order to really get these stories, we just had to be there when the mood strikes him because he’s not always in the mood to give it up. So we were just there for two and a half years. It was a long time.

You ask anybody close to him, Laura Dern, somebody who knows him really well, they’ll all say the same thing. “David is constantly creating.” If he’s not painting, he’s carving wood. If he’s not carving wood, he’s making music. If he’s not making music, he’s shooting a film. His passion and his energy all goes into creating non-stop. He’s not somebody who is like, “Oh, I’m going to take a vacation to Italy and go shopping.” No, into the studio, creative outlet.

KELSEY: On certain topics, did you guys try to push him further, or was it more about accepting what he was comfortable giving?

NGUYEN: We asked about certain things, but you know, the things he didn’t want to talk about… If you said, “Oh, the baby in Eraserhead,” or, “What was Eraserhead really about?” you wouldn’t get anything. It’s not like he would say, “I don’t want to talk about this,” he’s just not interested. We knew from experience, trial, and error that certain topics were off limits.

KELSEY: Did you feel like you got to a point where he was incredibly comfortable, or he kept a barrier?

NGUYEN: Incredibly comfortable. If you ask his daughter and his sons when they listen to these recordings, they would say, “This is dad. This is the dad that we know.”

KELSEY: Was there anything after you collected all of these stories that was going to be a key revealing moment? I think about the one story where he’s talking about him being a child and seeing that nude woman coming out of the darkness.

NGUYEN: Yeah, that was a major “a-ha” moment, but the other one I think was when he was talking about the anxieties he had as a young person saying, “Oh, I like to keep my art life separate from my family life from my friend life,” and he was kind of scared to let the three mingle. He was like, “I talked a certain way in the painting studio and I talked a separate way with my parents,” and he didn’t want his parents to go to his graduation and his friends never came over. He kept everything separate, which is kind of special. He was like, “Every youth, every teenager goes through anxiety,” but somehow David was even more pronounced. When I heard these stories I was just, “Well, it makes sense why in Mulholland Drive Naomi Watts plays different characters,” and how they’re separate characters. They’re the same person, but they’re completely different—different names, different haircut, different personalities. Same with Lost Highway, Bill Pullman can switch. The thing that confused me about his films when I first watched them, “Wait, why is he playing this other character right now?” Now I understand a little bit better because I’m like, “Okay, David kind of had different personalities also.”

KELSEY: There is still an element of mystery about him. He’s not totally raw in the film. There is still that mythic David Lynch persona.

NGUYEN: Yeah, he’s still closed off. He doesn’t talk about how he feels, necessarily. Even though his guards are down compared to with a journalist, he’s still David naturally where he’s still kind of guarded.

KELSEY: So, did you feel like you were able to get more insight into his interior life?

NGUYEN: I don’t know. We’ve had long discussions about this. There are certain subjects that I’m not going to talk about with anybody, even people close to me. We got him at his most natural. I think the other side, maybe he shows it to his wife. I don’t even know.

KELSEY: How does he feel about being in a documentary?

NGUYEN: He doesn’t search out the attention, that’s for sure, but he also knows that he made a deal with us, so he had to participate. [laughs] He was reluctant, even though he was open. He’s not doing it for the money, he’s not doing it for the fame, he doesn’t need that attention. He’s doing it because he made a deal with us that he was going to let us make a series of films about him.

KELSEY: Do you think that there’s another film to explore with him?

NGUYEN: Oh, yeah. There are probably many, but that’s not going to be us. [laughs] We contributed what we needed to contribute to the archive of David Lynch.

DAVID LYNCH: THE ART LIFE IS OUT NOW.