Icon

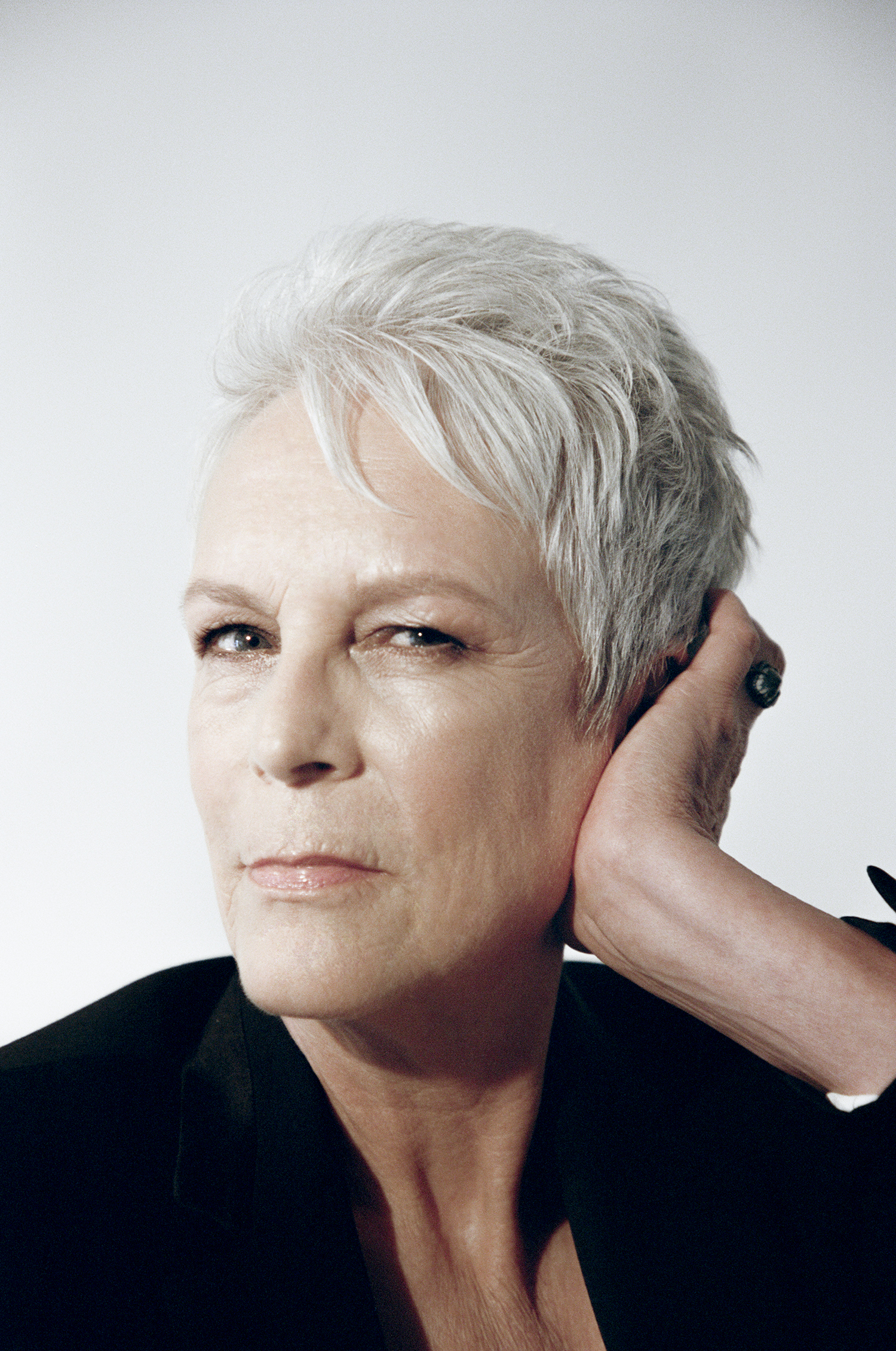

Jamie Lee Curtis and Melanie Griffith on Finding Love and Horror in Hollywood

Top by Celine by Hedi Slimane. Pants Jamie’s Own. Sunglasses (worn throughout) by Oliver Peoples. Earrings by Cathy Waterman.

Jamie Lee Curtis made her film debut at age 19 in the 1978 John Carpenter horror film Halloween. Cast as Laurie Strode, the first-time actress possessed such a potent mix of intelligence and innocence, soul and intensity, that the film not only launched Curtis’s Hollywood career but also made her character the prototype of the plucky, young heroine that horror movies rely on to this day. Stardom was not a guarantee, even while growing up in the center of the film industry with screen icons Janet Leigh and Tony Curtis as her parents. After the success of Halloween, Curtis made the rounds as a star of horror films—including The Fog, Prom Night, and Halloween II. A look at her filmography shows a dedicated actor who continually pushed away from typecasting and proved herself time and again as an accomplished comedian, dramatist, and action lead.

Over the decades, she’s arguably turned in the most memorable performance in such talent-rich films as Trading Places, Perfect, A Fish Called Wanda, My Girl, True Lies, Freaky Friday, and Knives Out. There is something disarmingly visceral and humanistic in her approach, a manner of telegraphing her character’s plight directly with the audience without pomp and obfuscation. She also seems to have a wicked sense of fun, and maybe the fun of her career brought her to return to the Halloween films more than once (she’s currently starred in six of them). But over the arc of Laurie Strode’s Michael Myers– cursed life, something fascinating has happened: Curtis has transformed her character from the “final girl” to the “final badass” intent on killing the monster once and for all. This fall, Halloween Kills, the second in a trilogy of Halloween reprises by director David Gordon Green, sees Strode take on the undying Michael Myers yet again. And maybe horror really does run in the family. Her mother starred in perhaps the most famous horror scene in all of cinema, stabbed to death in the shower in Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho. Here, Curtis talks to her dear friend, and the daughter of another Hitchcock favorite, Melanie Griffith, about starting out, staying sane in Hollywood, and why getting older doesn’t have to be a horror film. — CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN

———

JAMIE LEE CURTIS: Why do we call each other Miss Kiss?

MELANIE GRIFFITH: Keep it simple, stupid.

CURTIS: I was trying to figure it out. We’ve called each other Miss Kiss for a very long time.

GRIFFITH: Yes, we’ve known each other for 40 years. We’ve been through a lot, together and separately. But I have to say, I admire you so much, Jamie. You’re an icon.

CURTIS: Thank you, Melanie. That feels very endgame to me.

GRIFFITH: I have all these definitions of icon that I looked up, but I think one you would be happy with is, “An icon leaves a mark in history.” Which is what you have done, and continue to do.

CURTIS: I appreciate that. I have a new motto: “To die alive.” I want to die in an alive mental state. Getting older makes you more alive. More vitality, more interest, more intelligence, more grace, more expansion. I’ve been thinking about that because life is hard, and there are a lot of people who die in a really deadened state.

GRIFFITH: People get very complacent. You are definitely not that. You are just you. And you walk regally, by the way. You are very regal in your stance.

CURTIS: As you know, it’s a process. And for me, it was a big one. From when I was little, I didn’t want to be me. I didn’t even want to be Jamie. When I was in seventh grade, I asked my parents if I could change my name to Janie, because Jamie was a name that nobody had, and I struggled with that individuality. Of course, now I’m happy I have a name that’s mine. But Chris [Christopher Guest, Curtis’s husband] uses it against me in moments of intimacy to make me laugh, which is not when you want to be laughing. He will whisper in my ear, “I love you Janie.”

GRIFFITH: You guys have been married forever.

CURTIS: It will be 37 years in December. With Chris, I just wanted to make it work. It’s a marriage: It’s beautiful, difficult, funny, and really sad. It’s everything, because it’s real. We didn’t know each other when we married. We had never spent more than four days together consecutively before we got married.

GRIFFITH: I was there when you first saw him.

CURTIS: Yes. I had seen his picture in Rolling Stone, and said to my friend Debra Hill, “I’m going to marry that guy.” She said, “He’s with your agency,” and I ended up calling the agency and leaving my number with the agent, basically saying, “Look, I’m single, I think the guy’s cute, this is weird, but here’s my number.” And Chris never called me. Then I dated someone else and the night that it ended I took him to the airport, and went and picked up you and your then-husband Steven Bauer, who we met together on a TV movie called She’s in the Army Now. I remember the day you met him, because he walked by the makeup trailer and you said, “I’m going to marry him.” Or, you used a different word, but I’m not going to say it.

Dress (worn throughout) by Stella McCartney.

GRIFFITH: I think we all had that thought.

CURTIS: He is a very attractive man, and we were young. But, I picked up you and Steven, and we went to Hugo’s restaurant and sat down. Chris was sitting two tables away, and he looked at me and made a gesture that he had gotten my message, and I made a gesture back like, “Yeah.” And then got up to leave. He called me the next day, and we went out a few days later, and then he was leaving for New York to do Saturday Night Live. So, it’s a long marriage, but it was based on people who really didn’t know each other. It’s been a process of great fun and a lot of adventures, two children, and getting to know each other as who we really are, and carving a relationship out of it all.

GRIFFITH: I admire you for that. That’s a tough one. I know, because I did not succeed at that. I would love to talk to you about your books, because I know that in some ways, being a writer is more important to you than acting.

CURTIS: Yes. As an actor, you get a lot of attention, and it’s weird to get attention for something I didn’t write, because I’m interpreting someone else’s writing. But writing comes from me. When I wrote my first book, Annie [Curtis’s daughter] was four, and she marched into my office, and made a declaratory statement: “When I was little I used diapers but now I use a potty!” She said it with such fervor and self-ownership, so I wrote it down. Then I started writing more things she used to not be able to do, and could do now, and at the end, I wrote three things that made me cry, which is my barometer for truth-telling. I wrote, “When I was little I didn’t know what a family was. When I was little I didn’t know what dreams were. When I was little I didn’t know who I was, but now I do.” I realized that this was a book for children about selfhood and achieving. I wrote it, and sent it to a literary agent, who was my mother-in-law’s best friend. She sent it to Harper & Row [now HarperCollins], and they bought it that day. Then I partnered with [illustrator] Laura Cornell. I still remember where I was when Heidi Schaeffer, my friend and publicist of 40-plus years, told me the book had sold 50,000 copies. I didn’t write that book to make money. The reason it’s so important to me is because it was pure expression.

GRIFFITH: And authentic, and you.

CURTIS: And people like it. I didn’t have to take off my clothes, I didn’t have to be sexual, I didn’t have to play an ingenue, I didn’t have to follow my mother’s world. You and I shared that, from the beginning. What I was trying to say came out from inside me.

GRIFFITH: And all 12 of them have such a message. I read them to my children. The other day Stella was here, and she goes, “That was my favorite book. Do you remember mom?”

CURTIS: I get into a flow state when I’m writing these books. I once interviewed LL Cool J, who was in Halloween H2o, for Interview, and I asked him, “Can you really just freestyle rap?” And he said, “Yeah.” And I said, “Okay, make up a rap about mashed potatoes.” And he did. I get into a similar state when I’m writing these books. We were at a children’s birthday party in the mountains, and the party favors were helium balloons that were tied to a pole. The sky turned black, it started to rain, and we were all huddled under this corrugated tin–covered gazebo. This little kid pulled on a string and it released all the balloons. And this little girl pulled on her dad’s shirt and said, “Daddy where do balloons go?” In that second, I felt like I had been struck by lightning. We bolted from the party. I ran to my car, put Tom [Curtis’s son] in the car seat, drove home, handed Tom to Chris, and said, “Don’t talk to me.” I ran up to a guest room and laid down on the floor and wrote, Where Do Balloons Go? in one sitting.

GRIFFITH: Wow! That’s so beautiful. A lot of songwriters say that hap pens to them. I know Chris Martin has said that.

CURTIS: The muse hits you. That’s a long-winded answer to why they are important to me. It’s because it’s an inner voice, rather than an outer voice. The outer is something that you and I share and have wrestled with. What I’m interested in is how come we didn’t know each other?

GRIFFITH: When we were little?

CURTIS: Yeah. Was Tippi [Hedren, Griffith’s mother] friends with Janet?

GRIFFITH: I don’t think so. They had a weird Hitchcock thing. The sequence of actresses that worked with him, worked with him singularly. There was Grace Kelly, then your mom, then my mom, and Kim Novak. I don’t know how he was with your mom, but he apparently was not very good with my mom.

CURTIS: I don’t think Janet would have ever acknowledged if there was any bad behavior. She was, it’s a bad term, but kind of Pollyannaish about the industry. I think the #MeToo movement would have really upset her. It’s not fair to unpack that, because she’s dead and I’m going to put words in her mouth, but knowing her, I think she would not say that he misbehaved in any way. But it’s interesting that maybe our mothers were in competition with each other.

GRIFFITH: Maybe, but your mom was Hollywood royalty. My mom sort of became Hollywood royalty later, but she was an anomaly and didn’t last long with Hitchcock. That was a sad story. You know, she was of the #MeToo movement, and it was not accepted at that time. She was shunned and he made sure that she was shunned.

CURTIS: I don’t think Janet would ever have acknowledged anything, because from her standpoint, she was just grateful. That was very much her take. I think she would have looked at it as, “That was just the way it was.”

GRIFFITH: Well, I know mom really did have a hard time on The Birds. Physically, it was very difficult. Especially the end with the birds being thrown at her and all of that, she collapsed after and went to the hospital. It was a very sad time. Then with Marnie, he got very psychologically crazy with her and she couldn’t take it. I mean good for her, she stood up, but it really affected her career.

CURTIS: I knew that. And Janet and Tony were this golden couple in the ’50s, which added to their fame. Because when young stars collide in that way, there’s a different energy that’s created. I’m not saying my mom wouldn’t have stood up to him, but she was to her dying day nothing but grateful to Hitchcock and Alma [Reville, Hitchcock’s wife]. Obviously, we have been close girlfriends for a very long time, and we’ve talked about it personally, but it’s interesting that we didn’t know each other when we met on the TV movie and went to Barney’s Beanery to shoot pool and take tequila shots.

GRIFFITH: Well, I think you lived in Beverly Hills and I lived in the Valley. We weren’t around the same schools at all. You went to very prestigious schools, and I did not. Nothing against the Valley. It’s cool now.

CURTIS: It’s funny because most people assume that you and I grew up together. Were any of your childhood friends from show business?

GRIFFITH: Not until I was 16 and I went to the Hollywood Professional School. I went to five different schools from 8th to 12th grade.

CURTIS: I went to three high schools, but from 8th grade to senior year I went to four schools. I grew up with Kirk Douglas’s boys. When I was a young actress, I remember calling Michelle Pfeiffer and saying, “We’re always up for the same parts.” I learned how to read upside-down because you would walk into an audition and there would be the secretary at the desk, and I would be able to read the names of everybody who was coming in that day.

GRIFFITH: All of your competition.

CURTIS: I’d look down and go, “Fuck! Debra Winger. Michelle Pfeiffer, fuck!” So I called her one day and said, “I don’t know you and I don’t like not liking you because you’re my competition. Can we be friends?” We went out and had dinner, but we didn’t become friends, because that’s not really what makes friends. As you know, we became close friends right away.

GRIFFITH: My memory, too.

CURTIS: You were living in Malibu and had a party, and Heidi von Beltz was there. She was a stuntwoman who was paralyzed in a Hal Needham movie. I believe it was Cannonball Run, when she was doubling for Farrah Fawcett.

GRIFFITH: She broke her neck.

CURTIS: You had these parties, and you would always include Heidi. She would be carried in by her dad and would sit with us, and I remember thinking, “You are such an amazing friend.” You’re an incredibly loving and loyal, ride-or-die friend. And then men got in the way.

GRIFFITH: But we’ve always come back home to our friendship.

CURTIS: In an industry that is tricky.

GRIFFITH: You’ve turned me onto so many beautiful things, one of them being Children’s Hospital. We need to talk about My Hand in Yours.

CURTIS: I called Anne Ricketts, a sculptor who I collect, and said I’d like to start a charitable shop and venture called My Hand in Yours, and donate all of the money to Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. She said yes, and that started something, and then my friend Cathy Waterman joined in with this beautiful hand necklace, and we added more items and it kept growing. I’ve learned the power of daytime television, because I have appeared on The Talk and The View and Kelly Clarkson, and those have generated thousands of orders. By the time this comes out, I think we will have made $280,000 in our first year.

GRIFFITH: That is so beautiful.

CURTIS: Ideally, we’ll get corporate partnerships and then it can grow exponentially. Every actor I know would love to have had opportunities to do other work. But we did the best we could with what we got. I’ve done horror movies for a long time, and it took a long time to appreciate, because people in our industry like to categorize things and make them smaller and insignificant. There’s that term B-movies or B-queen. “She’s an A-lister or a B-lister.” My first movie was Halloween. Would I have liked it to have been an Oscar-nominated film? Sure. But, we base our lives on what came our way, and what we did with that.

GRIFFITH: Maybe in the beginning Halloween was a bit like, “Oh it’s a B-movie.” It’s not.

CURTIS: It becomes something bigger when it is given the support of the audience. The people who love these movies are so gracious and loving.

GRIFFITH: And loyal.

CURTIS: Because they recognize that it was a somewhat swept aside genre that they loved. I’m sitting in the exact same place I was when the phone rang and Jake Gyllenhaal said, “Hey, my friend David Gordon Green wants to talk to you about a Halloween movie.” I said, “Okay, have him call me.” At first, I said no.

GRIFFITH: When was this?

CURTIS: In 2017. Twenty years since my last Halloween. After I read it, I said yes. Because it was honoring somebody who suffered a terrible trauma at a very young age. That trauma was following her into her adulthood. What does that do to someone psychologically and emotionally? It turned out to be incredible.

GRIFFITH: Now there are two more coming.

CURTIS: It’s a trilogy that he and Danny McBride conceived, so there’s one being released this October called Halloween Kills. And one that will be released next October, called Halloween Ends.

GRIFFITH: Let’s talk about your podcast, Letters from Camp.

CURTIS: I’ve launched two podcasts. One is Letters from Camp, which was born from a letter that I received from my goddaughter, which she wrote from camp. Her mother had never sent it, and my friend Lisa Birnbach sent me a letter about a year-and-a-half ago saying, “Look what I found in a box.” It was a sealed letter, and it was very sweet. I called her right away, because she’s now a comedy writer, and said, Boco [Haft], this is a show, for sure.” We sold it as a scripted podcast. Boco writes it, and we got wonderful performers to be voices on it.

GRIFFITH: It’s so great.

CURTIS: The second one is called Good Friend. I felt like COVID was really tough on relationships, and there’s a song by Emily King that I love called “Good Friend.” The first time I ever heard it, I thought, that would be a really good radio show —because I’m old, so I would think of a radio show. And then I realized it was a podcast, so I wrote a proposal and sold it to iHeart as a podcast about friendship. Conversations with people I don’t know, and some with people I’m very close to.

GRIFFITH: I loved the conversation we had for that.

CURTIS: You and I have a long history, and I think people will relate, because we met in our twenties. Then we both got married and our lives drifted apart for 10 or 15 years. And then we found our way back, and it has reattached in a much stronger, more intimate way. That intimacy comes from our long lives as women—as mothers, as daughters, as wives and partners and actresses. It’s so deeply moving to me that we’re back together in such a deep way. You need to break apart to come back.

———

Hair: Lauren Palmer-Smith using Oribe at Home Agency

Makeup: Grace Ahn using Shiseido and Retrieve Skincare at Julian Watson Agency

Photography Assistant: Josephine Chumley

Fashion Assistant: Ari Govan