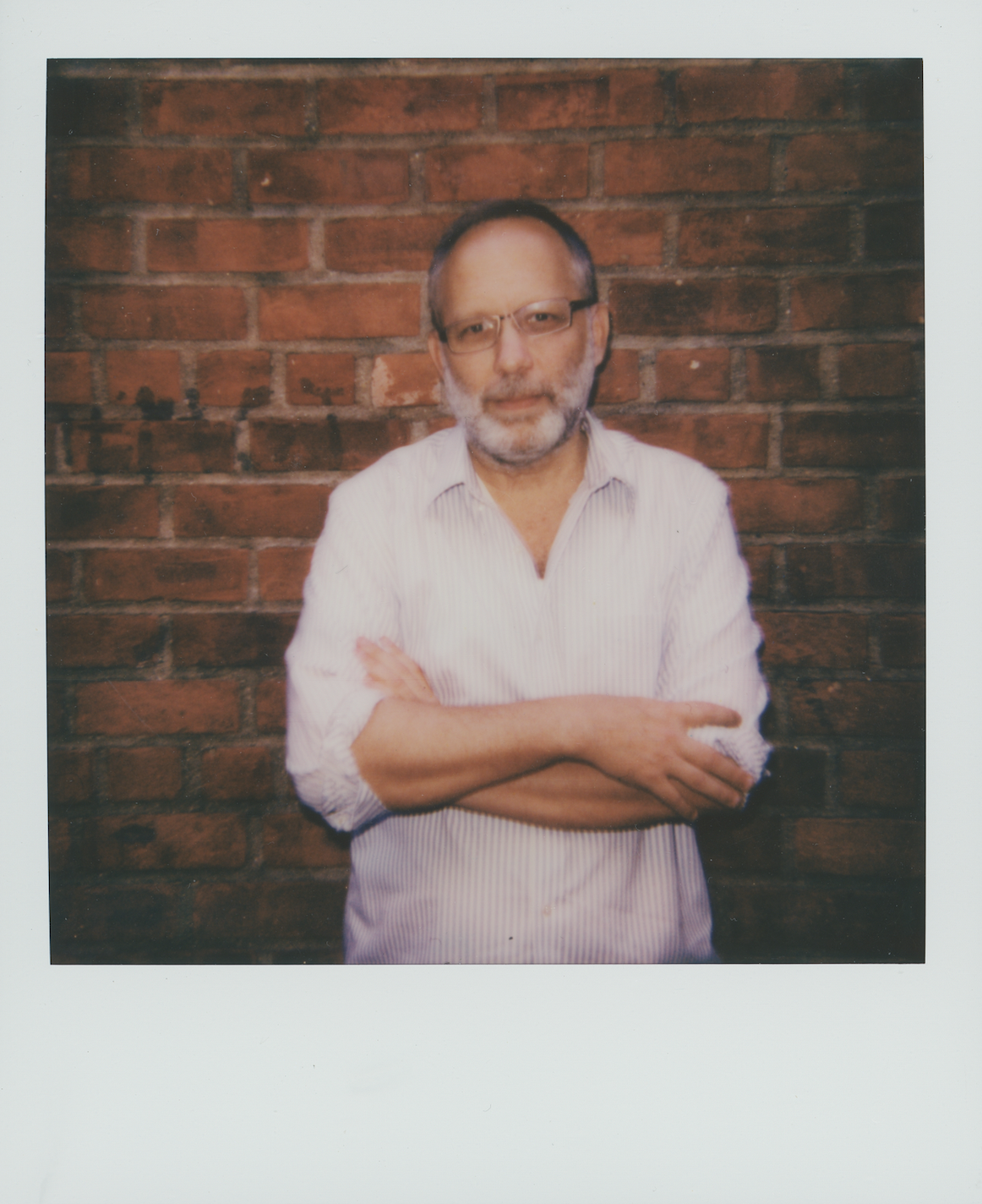

DIRECTOR

Ira Sachs on Fassbinder, Passages, and the State of Queer Cinema

In 2017, when I was a college student at Bard, I had a chance to invite the filmmaker Ira Sachs to campus for a screening of his raw, somewhat-autobiographical film Keep The Lights On. It chronicled the on-again-off-again relationship of Erik, a filmmaker, and Paul, a closeted lawyer, and Paul’s tumultuous addiction to crystal meth. I picked Ira up from the train station in Rhinecliff, which is where the final scene of the film takes place. It felt surreal, as if I was sitting inside of his movie. After the screening, we talked in front of an audience about the film, its gorgeous soundtrack of songs by Arthur Russell, and the state of queer cinema, and Sachs was gracious enough to join me at a bar where I picked his brain further. I was giddy and starstruck, but Ira was patient with me. Then I dropped him back off at the train station and bid him farewell.

Passages, Sachs’ latest film, is something of a return to form for the queer filmmaker. Like Keep The Lights On, it depicts the fraught relationship between husbands Martin (Ben Whishaw) and Tomas (Franz Rogowski), though their love isn’t jeopardized by addiction but rather Tomas’s affair with a woman, Agathe (Adèle Exarchopoulos). Sachs described Passages to me as “liberating,” but it was given an NC-17 rating from the MPA, undoubtedly for its honest depiction of sex between men. Last week, just before Passages hit theaters, I spoke to Sachs over Zoom about the film, why he finds the MPA’s harsh response to it homophobic, and his cinematic influences, including Rainer Werner Fassbinder and Chantal Akerman. Reinvigorated by his experience making Passages, Sachs also teased his next project, an adaptation of Linda Rosenkrantz’s book Peter Hujar’s Day, with Whishaw returning to play the titular artist.

———

CONOR WILLIAMS: You’ve been making films since you were in your twenties. I’m wondering how your films have evolved over the years, whether stylistically speaking or in terms of how you’ve practically approached filmmaking?

IRA SACHS: You know, I felt with this film like I was remembering instincts from when I was in my twenties. But I recognized that I had a different level of craft that comes with maturity. So in a way I could realize my most organic instincts on a new level, like it was the beginning of something for me, a new chapter of possibility. I also felt free because, particularly after the pandemic and approaching my sixties, I wasn’t sure I’d still be making movies. And the fact that I am gives me liberty. This is a movie without shame, in terms of both the images and the characters. Shame does not fuel this movie.

WILLIAMS: What do you mean by that?

SACHS: I guess my first several films were all about the illicit, the things that were hidden, because I lived in the illicit and it was both comfortable, enticing, and terrible. But I live in a different way now, and I think that’s reflected in the actions of these characters. They’re also a different generation than me, so I don’t feel that these three actors, or these three characters, learned about their sexuality with as much shame as I did.

WILLIAMS: The marketing for the film makes it seem like it’s gonna be about this kind of sexy threesome. And the film is very sexy, but it’s not really about that. It hints at this sort of alternate kind of romantic relationship, something outside the norms of monogamy.

SACHS: I know the film so well that I can’t even read the marketing like a normal person, so that’s interesting to me. I haven’t really thought about that. I think that the film is about the individuals bouncing off of each other in combustible ways. So if you asked me the genre, to me, it’s an action film, because I think it’s really about the impact we have on each other in unexpected ways and specifically in moments that can be captured by the camera and cinema. So in almost every scene, everything could potentially change.

WILLIAMS: I’ve heard some people make comparisons to the films of Rainer Werner Fassbinder. And I know you love Fassinder. And Franz Rogowski’s character kind of reminded me of Fassbinder himself. Was that a conscious reference for you?

SACHS: You know, what I took from Fassbinder for this film was beauty. Meaning, I wasn’t making realistic cinema, I was making iconic cinema. So I thought of the woman’s face, the man’s body, the costumes, the spaces as opportunities for visual impact. So we were looking at Beware of a Holy Whore, but mostly for wardrobe.

WILLIAMS: The sweaters are incredible.

SACHS: And also the color of the sweaters is incredible. And I think that in certain kinds of cinema, and Fassbinder more than almost anyone else, what lingers with you is the impact of color and bodies.

WILLIAMS: But there’s also a lot of pain and cruelty in this film.

SACHS: Yes. For me, pain in cinema is great pleasure because it’s not my own. Would you agree? Like Splendor in the Grass, the most painful movie ever made, is the most beautiful movie ever made.

WILLIAMS: Well, because there’s a distance as an audience member.

SACHS: Yes. And you’re projecting your own extraordinary wants and feelings onto the screen and the screen is projecting those same significant feelings back at you. Which does not happen in Marvel movies.

WILLIAMS: No, it doesn’t.

SACHS: There’s actually a repulsion of identification. And there’s also no sex, right? That doesn’t exist.

WILLIAMS: Well, you certainly didn’t make a Marvel movie. But I was thinking about The Mother and the Whore, which I just watched for the first time recently. I know you love that film. Is there any kind of connective tissue between that film and this one?

SACHS: Well, there’s a scene in the middle of this movie which is a direct homage to The Mother and the Whore, which is when two lovers play music for each other. And to me, making a film in Paris, I didn’t resist the memories that French cinema has given me. So it’s not necessary to know French cinema, but I think the film exists in a realm in which the pleasures of those movies is part of the film’s imagination.

WILLIAMS: Is that why you shot it in Paris?

SACHS: I shot it in Paris because I know the city very well. I’ve had relationships there and I’ve had breakups there and I’ve had sex there and I’ve cried there. So I feel really comfortable in Paris. And I also know what life is like intimately there. I’ve also been welcomed financially and supported, because in France, they’re still making a kind of personal cinema, which is in dire absence in the United States, particularly [if you want] a sustained career in personal cinema. You’re allowed to make one or two personal films, but then you have to do something else.

WILLIAMS: I want to ask you about this whole kerfuffle with the rating of the film. I’m assuming that the MPA gave this an NC-17 rating because of the sex scene between Ben and Franz. And there’s really nothing scandalizing in that scene. There’s been a lot of commotion about sex scenes in film. I asked John Waters about this and he was kind of horrified to hear that this has become something controversial.

SACHS: Yeah, I guess what frightens me is the warning shot this kind of censorship sends towards other filmmakers. It’s a moment in which people are told that if you create certain free images, you will be punished. So the system of control is trying to exert itself in a way that is pretty unique in the United States. This film was received at 12-plus in Spain, which is just a recommendation that it’s a film for anyone 12 and over who would enjoy and appreciate the film. As opposed to the United States, where no one under the age of 17 is legally allowed into certain cinemas. Half the cinemas in America won’t show the film. So that is a significant and successful form of censorship. There’s also this weird history of the MPA from the Hays Code in the late 1920s, which came from the Catholic Church. So you’re kind of like, “Why do we all accept this? Why does this progressive industry accept a nameless board of supposed parents to decide what we can see?” I mean, it’s kind of radical in terms of the control that a few people are exerting.

WILLIAMS: And they gave your film Love is Strange an R rating, right?

SACHS: Yeah. Tell me it’s not homophobic. I mean, I don’t want to be negative, but that’s like an after-school special.

WILLIAMS: When we met some years ago, and I brought you to Bard for Keep the Lights On, I asked you about the state of queer cinema. I’m wondering where we are now.

SACHS: Well, all I would say is look at the history of the most successful gay filmmakers in America and Europe and notice what stories they’re telling. I think that to have a sustained career in which the gay experience is central seems nearly impossible. And I think that means we have so few films. You know, for me, I have to go back to Taxi zum Klo and Je Tu Il Elle, a period of opportunity and abundance, for the kinds of images that I need.

WILLIAMS: You said that this film opened up a sort of freedom for you. Do you feel kind of reinvigorated going forward?

SACHS: I do. I feel like I want to make movies and I feel like maybe I can. I’m making a film in November with Ben Whishaw about an afternoon in December of 1974 when Peter Hujar had lunch with his friend Linda Rosenkrantz. Do you know the book?

WILLIAMS: Yeah. Is Ben playing Peter?

SACHS: Ben is playing Peter, yeah. It looks like it’s happening. We’ve got to get a waiver, but I’ll let you know if that comes along.

WILLIAMS: Thanks for this, Ira.

SACHS: Bye bye. See you soon.