An intimate new documentary reveals Arthur Miller’s truest self

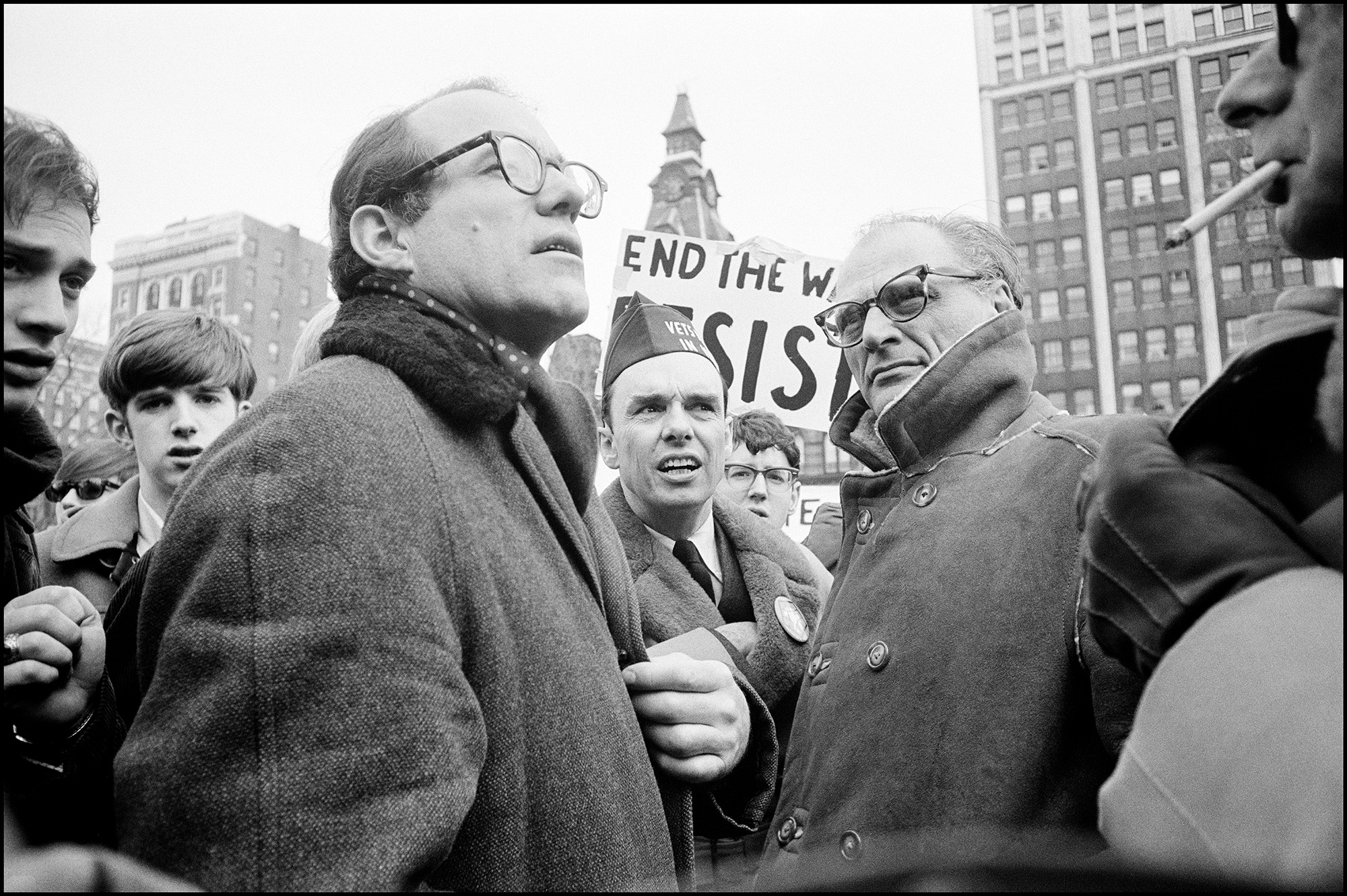

Arthur Miller is one of America’s essential playwrights. His plays Death of a Salesman, View from a Bridge and The Crucible provide some of the best snapshots we have of American life during the middle of the 20th century. Grown men cried after seeing Death of a Salesman in 1949 because they saw themselves reflected in the tragic figure of Willy Loman. Apart from his critically acclaimed work, Miller’s short and fraught marriage to Marilyn Monroe remains a subject of great interest to those still morbidly fascinated with the blonde bombshell’s death. Miller believed that tragedy was a confrontation with reality, and he pushed his pain into his writing.

When his daughter Rebecca Miller watched her father sit down for interviews, she noticed that he seemed to be a different man on camera than he was among friends and family. After winning the Gotham Award for her first film, Angela [1995]—about a 10-year-old girl and her dysfunctional family—Miller took it upon herself to capture her father’s true self. More than two decades after filming interviews with the playwright, Arthur Miller: Writer will premiere on HBO tonight. It’s a thorough and honest reflection of Miller’s life and legacy. Below, the director and daughter of the late playwright admits how difficult it was to capture such an enigmatic personality on film.

ALICIA KORT: How did you create that intimate of an environment for filming?

REBECCA MILLER: I think the relationship created the intimacy. The film dutifully reflects the kind of ease of being together that we had. We could just be together and not necessarily be talking all of the time or just sort of goofing around. For me, the reason I was doing it at all had to do with the access that I had, and I saw such a disparity in Arthur’s public self and his private self. I thought there was something to be gained by people understanding what he was like as a person.

KORT: Was there anything specific that you learned about your father that surprised you?

MILLER: His vulnerability as a younger man was interesting, particularly the letters and the evidence of the relationships he had on early on. You see him changing through those relationships and that was very interesting to me how the era of Mary, the era of Marilyn and how the era of Inge, my mother, seemed to shape him to a degree.

He was also so much a part of the history of the country. He was being created by the country and he was involved in some small part of influencing the cultural life of the country. On a personal level, some of the things he said about becoming awakened to the fact that he lived in a system and how much is being shaped by his personality and how much is being shaped by his forces during the Depression affected me. There’s something about cutting that film and seeing that statement again and again and thinking about what that means to think of yourself as a citizen of your country and the world just as much as in your own being, doing work that means something to you personally.

KORT: When did you start gathering footage and how long did it take you to cut it together?

MILLER: I started gathering footage because I just realized I wanted to be a filmmaker. I was in my twenties. I hadn’t even figured out what films I wanted to make, but I did just have this hunch that I better gather this stuff together or he was never going to be seen as who he was. I said to some friends, “Let’s go down and interview Dad and actually start doing this for real.” We prepared and went down and did a number of weekends. Then I got married, had children and got busy [making other films].

My intention when I shot all of this material was to cut it together as a film. I thought I might leave it to one of my kids or for posterity. And then after a while, I started to feel it as more and more of a burden. There’s all this Super 8 footage, all the family footage and all of the stuff, I just wanted it to be done. It started to feel like a monkey on my back. We found everything and then we started digitizing it, because it was in all different formats. It was in High 8, Super 8, VHS, 50mm film and then we started to also transcribe it all. It was 200 hours of film. I needed a transcription to give me a sense of what it was. It was so overwhelming, it just made me want to curl up. We put together a 15-minute reel and met [with] HBO. That’s when we started to think “We’re really going to cut this thing” [and] then began an odyssey that was 18 months long of actually cutting.

KORT: What do you hope to share with the world with this documentary?

MILLER: I really want you to feel like you’ve had a weekend with Arthur Miller, like you’ve spent the weekend with him but with privileged information you’ve never had—you read his letters, you know more about him actually than you would know if you spent the weekend with him and my mother. I found that the more real estate he had in the film, the better it got. The more people were happy to watch it. He is a compelling protagonist. You just want to be with him.

KORT: There’s so many great little details in this film that really give you an idea of who Arthur was.

MILLER: I love the detail when he gets $200 for his prize for the Hopwood Award and he says “$200 for a week’s work. I’m still accustomed to thinking like a laborer.” He still tended to break it down by the hour. It took him five years to get the money to go to Michigan. It was to me a great privilege because when anybody is with their parents, life goes by. You’re interested in yourself. It’s rare that you would stop and ask all of those questions to a parent, but you learn about yourself in the process. You learn about your grandparents, where you came from and it’s just a good thing to do for anybody really.

KORT: Arthur Miller was treated pretty unfairly by theatre critics during the counterculture movement. Decades later, at the very end of the film, in the 1990s, he and his plays have a sort of renaissance with The Crucible [1996]. Last year alone, there were three Arthur Miller plays on Broadway and a few films, like Assassination Nation [2018], have taken the premise of The Crucible. What’s it like seeing interpretations of his work evolve over time?

MILLER: He always said “Some of these plays were 50 years old and there’s not many things that are still useable that are 50.” It’s more like 60 years now, but it’s very true. They have renewed themselves for whatever reason. For me, in an odd sort of way, I guess I have an almost parental feeling about them now, which sounds a bit weird. I think that I feel quite protective. I’m always very happy if it goes well for him.

In the film, I ask him “What makes a play a great play?” He talks a bit about mystery, because essentially nobody knows the answers to this question. It’s[the play] starting to come close to something that nobody can really talk about. He starts to move toward something almost mysticism toward the end of the movie, which was a big surprise for me. All of my life he had been talking about the destructive elements of religion and how people end up going to war.

KORT: Arthur Miller’s mother seemed a little mystical with her strong sense of intuition. She sat up in bed and knew her mother was dead.

MILLER: In a way, she had a witchy thing going and had a clairvoyant quality to her sometimes. As much as he was repelled by that to a degree, because he was trying for a more rational approach to life, there was something that he got from her. That’s the part of his work that can’t put your finger on but might be part of the reason why the plays keep coming back. You can’t unpack it like a watch and say “Ah-ha! This is how it works.” It’s a mystery to him too. Sometimes I think he looked at his own work and thought “How did I..? What happened?” especially [with] Salesman, I mean it was almost like a visitation. It was quick. He wrote that first act in one night.

ARTHUR MILLER: WRITER AIRS MARCH 19, 2018 ON HBO.