Gary Oldman

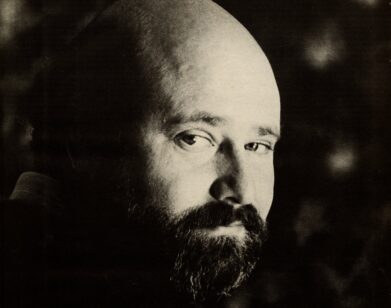

ABOVE: GARY OLDMAN

As a gruesome gangland trademark, the Irish thugs from Hell’s Kitchen dismembered their victims’ bodies before disposing of them, their motto being “no corpus delicti, no investigation.” Known as “the Westies,” they were branded “the most savage organization in the long history of New York gangs” by Rudolph Giuliani, who effectively prosecuted them into oblivion. It must have made Giuliani’s job a little easier that they were also among the city’s most, well, imprudent collection of criminals.

It comes as a relief, then, when Phil Joanou’s State of Grace, a powerful film inspired by the Westies, begins with haunting, fragmented images of a St. Patrick’s Day bagpipe parade in slow motion. It’s a little like a promise; what you’re about to see won’t be dumb or gratuitously vicious—it won’t beat you up. Written by two playwrights, David Rabe and the late Dennis McIntyre, the film ultimately suggests something broader in the Westies’ ruthless behavior, variations of which can also be discerned on, say, Wall Street, where outlaws are carefully disguised in blue suits and Hermès ties.

State of Grace is a surprisingly personal third film from Joanou, the 28 year-old whiz kid who broke into the industry as a protégé of Steven Spielberg. His first movie, a dark teen comedy called Three O’Clock High, was primarily an exercise in acquiring experience, and his second, U2: Rattle and Hum, was a rockumentary made with many cooks in the kitchen. Conversely, Jackie, the emotionally volatile hit man in State of Grace, is very much in keeping with the potent collection of rebels played by Gary Oldman, the extraordinarily gifted 32 year-old British actor who established himself in movies such as Sid Vicious in Sid and Nancy and as Joe Orton in Prick Up Your Ears.

It’s an important moment for a filmmaker when the press first previews his work, but Joanou wasn’t able to screen a pristine print that would do State of Grace justice. Instead, because of his prolonged X-rating battle with the MPAA, Joanou had to show a muddy, scratched work print; Orion wouldn’t let him cut the negative until State of Grace received an R. But despite these circumstances (or maybe because of them), Joanou and Oldman grew cheerier, as we talked, by the beer—first Harps, then Rolling Rocks, in keeping with their film’s New York Irish theme—until they were loose enough to re-create Oldman’s first encounter with his notoriously touchy co-star, Sean Penn. While Joanou had waited for a fight to break out, Oldman sang “Like a Virgin” at the top of his voice, imitating Penn’s ex-wife with exaggerated dance movements. Penn laughed, however, succumbing to Oldman’s decidedly devilish charm.

Perhaps Oldman and Joanou’s ease during this interview had something to do with the fact that it took place in the Landmark Tavern, one of Hell’s Kitchen’s spiffier establishments, where the two spent a lot of time while making State of Grace.

RANDY SUE COBURN: Did you know that this was the place where Mickey Coonan and Jimmy Featherstone [two infamous Westies] shook down an official from the longshoreman’s union?

PHIL JOANOU: Yep. How’d you know?

COBURN: From T.J. English’s new book about the Westies—have you read it?

JOANOU: Not yet, but I read so many newspaper and magazine articles about the Westies, I’m probably familiar with all the material.

GARY OLDMAN: I never read anything before the film started, did I?

JOANOU: No, and I think that was one of the amazing things about Gary’s performance. [Oldman leaves to take a telephone call] It was completely instinctual. His technique was almost invisible—you couldn’t even figure out if there was one. But from the way he understood everything about Jackie, how he’d behave and speak and move, it was almost as if he’d lived in Hell’s Kitchen for three months.

COBURN: Jackie does seem to thread together with other characters Gary’s played, though.

JOANOU: There’s a thread of intensity. And he has high standards for the material, and he’s willing to take risks. Gary was the first actor to commit to the film, the only one ever even considered for Jackie, but he took a huge risk working with me. They all did. I mean, these guys are established. [Oldman returns]

OLDMAN: I committed to the first draft of the script, and I hadn’t seen any of Phil’s work.

JOANOU: Gary’s psychotic, that’s what he is. Totally nuts.

OLDMAN: That’s why I can play Jackie. [laughs] But when I said I’d do it, I was bullshitting my way through the whole fucking thing. I mean, I didn’t know I could do this character. He just sort of came. He just sort of appeared—very late on, actually. Right before shooting.

COBURN: Weren’t you concerned?

OLDMAN: Well, you always hope that the cloak of inspiration will fall, and you’ll be O.K.

COBURN: Given your performance as an American in Criminal Law, it’s obvious you’re a terrific mimic. But the accent for Jackie is so different—it must have come along well before shooting began.

JOANOU: I knew he had it about a month after he agreed to do the part. Gary came to New York, and we were riding around in a cab one right when he said he’d been working on the accent, listening to some tapes. There’s a scene where Jackie’s brother hugs him, and Jackie says—

OLDMAN: [with Jackie’s accent] “Frankie—you ain’t done that for years.” But, you know, even with my relationship to the film, nothing was really bashed out and intellectualized. Obviously, Phil did his homework in terms of what was to be shot that day and how it was to be shot, but it was very loose within what he wanted. I think filmmaking should be a wonderfully free collaborative process, and it so very rarely is. I often see directors as jailers of my talent. But this was a give-and-take situation. If I had an idea and Phil liked it, he adjusted it to that, or he’d explain to me what he was doing.

COBURN: It’s a way of working that seems to correspond with the style of the film, in that there are far more close-ups than most directors use. The actors’ faces are really out there.

OLDMAN: I like that in particular, because as an actor, that’s your landscape. But I think that style really evolved with the shooting.

JOANOU: I just kept moving in and in and in as the movie progressed, because so much of what was interesting to me was coming from their faces. I think it’s a character-driven film, really.

COBURN: Did you go to the dailies, Gary?

OLDMAN: No, I never do.

JOANOU: But dailies were open to anybody—the actors, the crew, whoever wanted to come—which isn’t always the case. To me, that’s the whole reason you’re doing it; the fruits of your efforts are on the screen; that’s what you work all day and night for. A lot of actors came quite often, but you chose not to.

OLDMAN: Well, I like to believe that I’m really there, that I’m in the same situation as this character. And if I then see it, I realize it’s just an illusion. It spoils it, because I can be objective and monitor myself. A little someone nudges me and says, “It’s only a movie.” It takes the winds out of my sails. I realize it’s artifice, that it’s make-believe, that I’m not that man, and I don’t kill people. I know that much—but beyond that, I don’t want to know.

COBURN: I read that your sisters had been married to small-time gangsters. Was urban violence part of your upbringing?

OLDMAN: Yeah, but not so heavy as this. Now and again someone would get shot. My brother-in-law got shot once, actually. He came out of a pub one night and someone drove past in a car and shot him. The bullet went through his leg, and into his father’s leg.

COBURN: Has that sort of thing influenced your performances?

OLDMAN: Subconsciously, maybe. It gives you color.

JOANOU: I grew up in Southern California, not in an urban environment. But I think violence is something you’re attracted to or repulsed by, and it’s always something I’ve been attracted to in dramatic terms. I mean, most people don’t seek it out in their lives.

COBURN: Maybe they do to the extent that they buy a ticket for a Sylvester Stallone movie and get off on it in the theater.

JOANOU: Yeah, but that’s entertainment. No one would want rocket launchers going off in their own backyard.

COBURN: As wild and vicious as Jackie is, he’s actually the film’s purest character, the only one who’s not actively betraying another. Jackie is worlds apart from his brother Frankie [Ed Harris], who’s very cold and calculating.

OLDMAN: I’ll tell you what’s also interesting. On the surface of it, my language in the film is full of four-letter words, but that’s mixed with a kind of poetic elegance. It’s terribly subtle, but the tune, the lilt, is still very Irish even though it’s New York slang. It gives a kind of pelt bristling beneath the cloth.

COBURN: It’s really through Jackie that the story’s Catholic underpinnings come through. When he’s upset, he hides out in the Church of the Sacred Heart—desecrates it, even.

OLDMAN: Just the fact that he kills people is a desecration. But the faith is in his blood, even though he would deny it.

COBURN: See if you relate this passage from English’s book about the Westies: “In Hell’s Kitchen… you choose between good and evil at a young age. If you choose evil, then violence became an important means of communication; a way of showing a friend just how far you were willing to go to prove your friendship.”

JOANOU: That is the theme of the film.

OLDMAN: Yeah, it’s like your buddy is your brother. Somebody you don’t know, he can be a cocksucker and you’ll kill him.

COBURN: Since you’ve portrayed the Westies as anachronistic hoods who face extinction in a sort of elegiac slow-motion shoot-out, I’m naturally going to bring up The Wild Bunch.

JOANOU: I’ve never seen The Wild Bunch. What’s that?

OLDMAN: [laughs]

JOANOU: I’m kidding. Of course, I had a cassette on the set with me at all times.

COBURN: Sounds like you’ve heard this one before.

JOANOU: Obviously, Peckinpah is one of my favorite filmmakers. And thematically, there’s a parallel relationship.

OLDMAN: Phil is young of years—

JOANOU: So it’s just a phase I’m going through?

OLDMAN: Well, I do this think this is a very seasoned piece of work for a director so young. We all borrow, or lend. I remember seeing Anthony Hopkins in Pravda, and I thought it was such an amazing performance I thought, “Right, I’m going to nick that and make it my own.”

JOANOU: What inspires you is part of what makes you want to be an artist. But without the writers and the actors, I would have been left with nothing but technique, and nothing but my own point of view in terms of execution, which is ultimately worthless. All that matters to me is emotion in a film. I mean, when Sean Penn did his monologue, I choked up on the set. I don’t get choked up about, like, a great Steadicam shot. What’s a three-minute tracking shot or beautiful lighting? That’s time and money, actually. That has nothing to do with emotion.

COBURN: But do you really object to people detecting traces of movies like The Wild Bunch and Mean Streets in your film?

JOANOU: Yeah, you’re right. Better those than, well, some others.

COBURN: The violence in State of Grace is very abrupt, very sudden and precise. What was the reasoning behind that approach?

JOANOU: Except with the final confrontation, which becomes more thematic, that I was going for was that the violence comes out of nowhere. Some one asks you to have a drink and you kill him because you think maybe he killed your buddy. These guys have some serious logic problems, and Jackie kind of personifies their craziness—living by the moment.

COBURN: A number of highly regarded filmmakers have recently received, or been threatened with, X ratings from the MPAA. Because of the violence in this film, you’ve had trouble getting an R rating.

JOANOU: Well, the board in Los Angeles has given us an X rating seven times now, unanimously. The cut you saw was rated X. I’m in the middle of a heavy situation with them. Their theory is that violence in a cartoon like or comedic or action-adventure situation has less impact, and is less emotionally disturbing than violence that is portrayed in a “realistic” situation.

COBURN: I would love to hear them try and defend that slippery slope. Die Harder blows away over two hundred people and gets an R rating, but your film with a tiny fraction of those deaths, merits an X. Are they saying you shouldn’t show people what violence really looks like and run the risk of disturbing them, but that it’s O.K. to glorify violence so that they can enjoy it?

OLDMAN: Their thinking is that a 15 year-old sees something graphically violent, he’ll copycat it. But I think that showing something, the result of something like what a knife does when you cut someone across the face could be valuable, because can’t it work the other way, where you see that and think, I never want to do that to anyone?

JOANOU: What’s often so irresponsible in acceptable movie violence is that there is no repercussion, there is no result. Or if there is a result, it’s—

OLDMAN: It’s heroic, that’s what it is. It’s exploitative, it’s manipulative, and it’s heroic.

JOANOU: In fact it’s pathetic, and that’s the whole point.

COBURN: It must have really diluted the experience for you, having to show a messy work print in press previews.

JOANOU: Oh, tell me about it! You’re ready to deliver the picture, show it to people, be proud of it, and instead, two feet away from the finish line, someone trips you and you fall on your face. Then you’ve got to crawl, inch by inch, over the next few months, and it’s terrible. Just emotionally, it drains everybody.

COBURN: What sort of cuts have you made to appease the MPAA?

JOANOU: I’ve made some that I feel don’t change the film radically—you probably wouldn’t even notice them on a second viewing, they go by so fast. I haven’t had to take scenes out, or even shots. They’re trims, adjustments that are necessary to achieve any kind of movement out of the MPAA. I’m comfortable with what’s been changed to date, but about two weeks ago I refused to go any further, and the studio supports me.

COBURN: Do you think the MPAA’s standards have changed with the current political climate?

JOANOU: Part of the problem is a lack of consistency—it’s different for every film. But I do think a wave of conservatism has come over the country. Look at the NEA and what’s happening with music. It’s happening everywhere.

COBURN: Does this sound like to you, Gary?

OLDMAN: Well, Thatcher has single-handedly brought the arts to its knees in England.

JOANOU: People talk about the ’90s, like, “Thank God we’re out of the ’80s.” Give me a break.

COBURN: The version of State of Grace that I saw ran over two hours. Will you have to cut for length as well as violence?

JOANOU: No. I’m aware of an attitude in the media that the studio isn’t being heavy enough, implying that maybe there is too much freedom for the filmmaker. What a disservice to the fucking medium of film, for them to knock one of the few major studios that’s willing to get out there and roll the dice and take a risk on films that are trying to push back the edge a little bit. It really frustrates me.

COBURN: I heard you once considered using the tag line “it’s about being Irish.” For a movie that doesn’t really condense into a two-sentence synopsis, that sounds like a pretty good hook.

JOANOU: I don’t know what we’ll use, but it’s not easy, marketing a complex dramatic film. A year ago right now, when we were out there shooting, I couldn’t give a shit how we were going to sell this movie and get people to see it. You just want to get the best work on the negative. And now it’s like—

OLDMAN: The baked beans are in the can—how are we going to sell them?

JOANOU: I guess the question is, can you reach people today with a film like State of Grace, particularly if you are not Francis Coppola or Martin Scorsese or Bernardo Bertolucci.

COBURN: I don’t know, but I do know that not many filmmakers today have the opportunity to try and answer that question.

JOANOU: No, they don’t. I’m very lucky in that respect.

COBURN: Were you told the film would be an easier sell if the love story between Robin Wright and Sean Penn had a happier ending?

JOANOU: Yes, but not, thank God, by the studio.

OLDMAN: What’s Terry supposed to say? “Baby, I love ya. I just killed your brother, now whattaya wanna do for dinner?”

COBURN: Her part is unusually well-written for a woman in this kind of film. If there’s a good guy here she is the one.

OLDMAN: Jackie’s a good guy!

JOANOU: He’s not—but he thought he was.

OLDMAN: He’s a sweetheart. I miss him. I just think he needs a good cuddle. [laughs] He’s a very tormented soul, Jackie. The reason I like characters like him is that they are bright, they’re passionate, they have got the gift of gab. I mean, Jackie should go to drama school!

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN THE OCTOBER 1990 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.