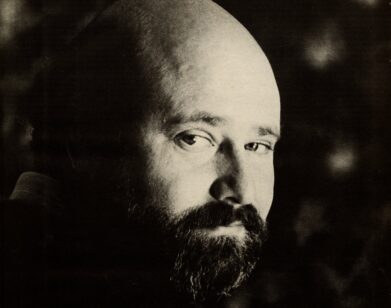

Donald Westlake’s American Tribute?

Anna Karina, courtesy of Photofest; Jean Pierre Léaud and László Szabó, courtesy of Rialto Pictures

The world of film noir is a little less illuminated now, following the death last week (at age 75) of prolific mystery writer Donald Westlake.

Westlake penned more than 100 novels, but also made important contributions to film. He wrote five screenplays, including a treatment of Jim Thompson’s The Grifters; the 1990 film (directed by Stephen Frears) earned four Oscar nominations, including one for Best Adapted Screenplay. More than a dozen movies in the last half-century have used his hard-boiled novels as their source, including Payback (1999) and John Boorman’s Point Blank (1967).

Jean-Luc Godard’s 1966 film, Made in U.S.A., which begins a two-week engagement at Film Forum (and short runs elsewhere) this Friday, occupies an odd spot in Westlake’s film resume. Godard adapted Westlake’s book The Jugger, but he never bought the rights, and the author sued him. As a result, the film was never released in the U.S.—until now.

What made Westlake (who authorized the film’s theatrical release before he died) change his mind? For one, Made in U.S.A. has much more to do with Godard, and the 60s, than the book on which it’s loosely based. It’s got “all the electric thrill of a Rauschenberg painting in motion,” in the words of critic Jonathan Rosenbaum. It’s got Marianne Faithfull singing “As Tears Go By” in a bar, a propos of nothing, while a laborer across the room talks semiology. And it’s got candy-colored Mod ensembles worn by star Anna Karina (in her last Godard collaboration), which have inspired generations of ingenues, and recently much of by Agnes B’s Fall 2007 collection.

In an interview he gave during filming, Godard explained, “I started off intending to make a simple film, and for the first time I tried to tell a story. But it isn’t my way of doing things. I don’t know how to tell stories … I couldn’t prevent myself from filling in the sociological content. And this content is that everything now is American-influenced.” Of all Westlake’s cinematic accomplices, Godard was perhaps the least grateful. Westlake, to him, was from a different (and somewhat hostile) planet. But he was also a cinema-friendly writer, and it’s possible that Godard, a pastiche artist with a thing for crime thrillers, intended this very idiosyncratic adaptation as a compliment. Even if he never paid for the rights.