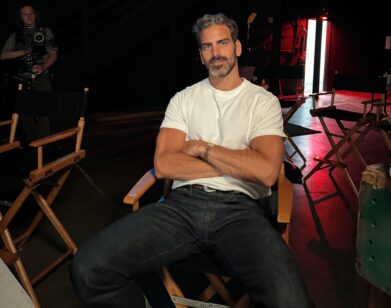

Discovery: Tom Lipinski

ABOVE: TOM LIPINSKI IN NEW YORK, DECEMBER 2013. PHOTOS: VAN SARKI. STYLING: MARY FELLOWES. STYLING ASSISTANTS: PAULINA OLIVARES AND JAMES GALL.

If you think actor Tom Lipinski looks like Josh Brolin, he’s heard it before. Later this week, you can see him play a younger version of Brolin’s character in Jason Reitman’s drama, Labor Day. “I felt inherent in someone saying ‘He looks like Josh Brolin’ was: ‘When he’s actually Josh Brolin’s age, then he’ll be in his wheelhouse,'” jokes the 31-year-old. “Nobody had ever said I look like Brand from The Goonies.”

Lipinski isn’t one those actors who, as Megan Mullally put it, “came out of the womb in a top hat and tap shoes.” The son of a neurologist and teacher, Lipinski explains that growing up, “I didn’t know any people in the entertainment business: nobody’s father or mother or uncle. I had no ability to even imagine myself doing something like that.” Even in college, Lipinski says that “the parameters of my life didn’t allow for me to imagine that as a possibility.” Rather, Lipinski went to Brown, studied history, and played on the lacrosse team (don’t worry, he was the team’s token rebel—before the team photo, he shaved his hair into a Mohawk and died it black). It was only after graduating that he found himself living in New York doing experimental theater. After recurring roles in network television shows such as The Following and Suits, Lipinski’s career is about to take off: this autumn he’ll appear alongside Clive Owen in Steven Soderbergh’s highly-anticipated small-screen debut, The Knick. Set in New York at the turn of the 19th century, the show will follow several employees of the now-defunct Knickerbocker hospital as they try to track down Typhoid Mary, among other things. “The city that’s represented is such a foreign, dangerous place,” he explains. “It gets me excited as someone who can get turned on by historical fiction.”

We met Lipinski earlier this week in New York.

HOMETOWN: I grew up in New England, in Massachusetts.

FORGOING THE FAMILY PROFESSION: I remember my father telling me: “You should be a doctor.” I was like, “Dad, I hate to tell you, but I fucking hate science. I’m no good at it. The idea of being a doctor is very appealing, but as a student who’s bad at science, and someone who gets almost no enjoyment from it, I think I’m stuck.” And he was like, “No, no, no. Going through school is like doing the jogging during pre-season, nobody likes jogging, nobody likes doing exercise, but you do it so you can play in the game. Being a doctor, that’s like being in the game.”

BROTHERLY LOVE: I actually have a newfound respect for tape recorders. My brother used to work for The New York Times. He just moved to New Orleans and is working for The Times-Picayune. Right before he left, he got sent by The New York Times to Ghana to write a story for the magazine, so he was doing all of these phone interviews about his time there. He was like, “I’m up against a deadline, can you transcribe the interview? It’s a 45-minute phone interview with two other guys. It’s fine; it’s easy. You’re a fast typer. You’ll be able to do it.” Eight hours later… what a terrible, terrible thing to do to somebody, or yourself.

ODD JOBS: I used to work at LimeWire. The entire time I was at LimeWire, I was auditioning on the sly. No one really knew I was an actor, I was the kid in the coveralls who fixed the plumbing occasionally. Did I really wear coveralls? Yeah. They didn’t tell me that I had to, but part of me was like, “No, no, no. I should.”

In between my junior and senior year of college, I was a substitute kindergarten gym teacher. I had to teach on my knees because I was so much bigger than the kids that when they would first see me they would start to cry: “Who is this hulk-like giant?” I was also the co-ed soccer coach. That was a scary experience.

IF YOU CAN’T ACT… A lot of acting teachers say, “If you can do anything else with your life, you should do that, because acting is too hard for people who have other passions.” That’s really bullshit if you think about it. Anybody can do anything else. It’s not like, “I can only act,” unless you had so little self-confidence that you think you literally couldn’t do anything else. It’s particularly hard because acting isn’t really contingent on your desire to do a good work or to be involved. You can’t act in a vacuum.

THEATRICAL ROOTS: I’ve done a lot of strange theater. When I first came to New York I did experimental theater, which I don’t think is necessarily how a lot of people start out. I got involved with a group in Providence, Rhode Island called The Theatre of the Two-Headed Calf, which, you can imagine… Through them, I met a whole bunch of other people, experimental theater groups, and I moved to New York to do that. I did a lot of theater at La Mama and the Ontological—Richard Foreman’s old theater. A lot of site-specific theater. Then I started doing stuff at the Flea, which is more straight plays.

ACCIDENTALLY AUDITIONING FOR ARONOFSKY: I was going to castings out of Backstage. I probably even went to auditions advertised on Craigslist, which has to be a bad idea. I went to “One on One”: actors pay about 25 bucks to have an audition in front of a casting director or casting assistant. Not for anything in particular, but just so that casting person can see you. The casting person that I went to spent my entire audition with her head in her hands. She wasn’t looking at me or anything. After I left, I thought, “That went really terribly.” She called me the following day and was like: “I was having a terrible migraine, but through the migraine I thought you were sort of funny, so I feel bad that I ignored you during your audition.” So she allowed me to come in and audition for a small role in a movie they were doing. I read for it, and she said, “That was great, can you come back in a couple of hours because the director’s going to be here.” I said “sure.” There was a director and a producer in the room, and I read for it again—it was just a simple scene. She called me that night and said, “You got that job.” And she told me the director was Darren Aaronofsky…

FIRST FILM: …So I was in The Wrestler. Later I was cut out of the movie, but that was the genesis of me getting a manager and starting to audition for actual things in earnest. There was a backstory about Mickey Rourke’s daughter being in AA. He’d abandoned his daughter; his daughter had become a drug addict and run off or something at a young age. She comes back and they try to reform their relationship. They have this meet-cute as father and daughter, and I interrupt as this superfan with this other guy: “Yo, dude. Can I just get a picture with you?” The one piece of proof that I have that I was actually in the movie is, we did the scene, like, 30 times, and in the scene we asked his daughter to take a picture of us. We kept handing this camera over, kept handing this camera over. Only later did I realize that it was an actual camera with a memory stick in it that had taken 30 photos. In the back of my mind, I was like, “I should just steal this memory stick so I have all these photographs.” Did I? No, I thought that probably wasn’t the best thing to do on my first day on a feature film . So I begged and pleaded with the AD to send me the photos. Six months later I got an email with 30 of the same photograph. The picture was good enough.

BRO’ING OUT WITH BROLIN: We had a producers’ dinner the day before we started shooting Labor Day. He came in a little late and everybody stood up and he sort of ignored me at first. But then, as people started to filter out at the end of the night, he grabbed me and said “No, no, no. You and I—we sit down and talk.” And after everybody left we sat there and talked for about two hours, which was awesome. He had just come off of Men in Black III, where he was playing a young Tommy Lee Jones, and he was fresh off a huge media press tour, so we talked about that, we talked about playing a younger version of people. It was like being thrust into Hollywood.

I’d watched all his movies in the lead up before we started shooting. He’s a really great actor—but how are you going to attach yourself to a gesture, or to an appearance of a character, or a person that in every movie is trying to do something different? I remember asking if I could be on set when he was shooting just so I could have greater insight into what he was trying to do with the character. But ultimately, and he’d said as much, it’s just about doing what’s written on the page and trusting that the writer has effectively, which I think Jason [Reitman] did, represented the character in two different times of his life. When you get on the set, you take all the things that you’ve thought about and studied and learned, and go, “Well, I hope it seeped in! I hope it’s there when I’m calling on it.”

GETTING RECOGNIZED: One of the first times that somebody recognized me was on the 6 train. A guy got on at Astor Place —a big guy with an army jacket on and a thing of flowers in his hand and he was looking at me—staring at me. I was like, “Fuck, I’m in trouble. I don’t know what I did, I don’t know if I looked at him wrong I was getting up to get off and he stopped me with his hand and said, “Yo man, you’re Trevor.” And the first thought that went through my mind was, “Fuck. He has me confused with some guy named Trevor who fucked him over.” He was like, “Take it easy on Mike,” which is a character from Suits—I played Trevor, “Mike’s my boy.” I was like, “What? Okay…yeah. Wait, what?” I got off so confused that he’d big-leagued me: he’d recognized me and was talking to me as if I was my character. That’s happened a couple of times. It’s usually from Suits and people are like, “Aw, man. I hate you. You’re such a punk.” When someone’s like, “Oh you were in The Following!” I’m like, “You shouldn’t like me from The Following…”

LABOR DAY COMES OUT IN THEATERS NATIONWIDE TOMORROW, JANUARY 31. THE KNICK WILL AIR ON CINEMAX IN FALL 2014.