A Dinosaur Named Sue

Twenty-four years ago on the Cheyenne River Indian reservation in South Dakota, a group of paleontologists led by Peter Larson discovered one of the most complete Tyrannosaurus rex skeletons to date. They named it Sue—after the member of their group who first spotted a few bones—and paid the landowner five dollars to take it with them back to their research center, the Black Hills Institute. Their plan was to use Sue as the centerpiece for a paleontology museum in their hometown of Hill City, South Dakota. Within two years, however, Hill City, whose current population of hovers around 1,000, was swarming with federal agents and the National Guard. Sue was seized and put up for auction by Sotheby’s in New York.

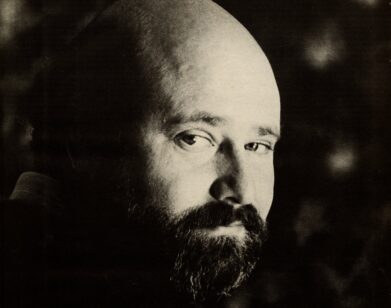

Dinosaur 13, which premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in January, tells the story of Sue through the lens of the Black Hills Institute. Directed Todd Douglas Miller, it is less a documentary of discovery, and more about the politics of science and the rift between those with money, those with prestige, and those with passion. “I wanted to tell the original discoverers’ side of the story,” Miller explains. “I wanted to do a film was dealing with one man’s obsession and what it did to him over a prolonged period of time.”

“I definitely like stories that deal with discovery and adventure,” says Miller of his feature-length debut. “This had everything in it, and it had dinosaurs.”

EMMA BROWN: How did you first come across the story of Sue?

TODD DOUGLAS MILLER: We had packed up the truck in Brooklyn to get out of town for a while, and spent a summer doing an art film on paleontology and science. We were interviewing a bunch of curators and museums all over the U.S. Along the way I read Peter Larson and Kristin Donnan’s book Rex Appeal, and they were last on our list to go and interview. I went to Hill City, South Dakota and I was just taken aback not [only] by Larson as a person, but also their facility, the Black Hills Institute, and just how open they were to granting us access. After spending about a day with them I told the guys I was with, “I’m going to see if I can option this book, and we’ll just scrap everything we’ve been shooting for the last year.” Hollywood had been banging on [Larson and Donnan’s] door for years and they turned them away. I came at it with a different approach: we want to do it in first-person narrative where we get everybody on camera, as opposed to hiring actors. They were receptive to that and three years later, here we are. I’ve joked before [that] I’m not a full-blown nerd but I’m halfway there. This film has definitely thrown me back into nerddom. I feel like I can go teach a course on vertebrate paleontology now.

BROWN: Was the rest of your crew keen to scrap everything you’d worked on before meeting Larson or were they upset?

MILLER: Well, it was only one guy—my director of photography, Tom. I think everyone appreciated that it was going to be a better film. I’d been talking about this Peter Larson guy while we’d been on the road; I knew a little bit about Sue when I started the project, and we were going to integrate it into the story somehow.

BROWN: Larson is a self-taught paleontologist. Do you think that people would have treated him differently—that the outcome for Sue would have been different—if he’d had been a classically educated and had a PhD?

MILLER: It’s interesting because pretty much all of the major paleontologists working today… for instance, Jack Horner at the Museum of the Rockies is one of the most famous paleontologists. [He] doesn’t have a college degree, yet he was the curator of the Museum of the Rockies, his students are world-renowned scientists in their own right scattered throughout the world. I equate it with scuba diving: there’s Jacques Cousteau and all of these big people, none of whom got certified as scuba divers. That’s the same thing you find with paleontology: a lot of the forward-thinking guys, a lot of the ones that have pushed the boundaries of what science is, don’t have degrees. They teach it at universities. But the flip side is true too: Bob Bakker, Jack Horner’s biggest rival, has two PhDs. I think in Peter’s case, [not having a PhD] hasn’t hurt him at all. He grew up in Mission, South Dakota, which just happens to be a stone’s throw from where every major Tyrannosaurus rex ever lived and is now fossilized in the ground. The reason why he’s collected more T. rexes than anyone else on the planet and is the world expert on T. rexes, is because it’s in his backyard.

BROWN: Are the residents of Hill City still upset about the loss of Sue?

MILLER: Yeah, it’s crazy. We had the film played at the Black Hills Film Festival—that was one of the deals that we made with whoever was going to pick it up the film at Sundance—and it was like a religious event. There are some people who have never gotten over it. We don’t talk much about it in the film, but Peter had three kids and they are still trying to come to terms with it. Imagine being five to 10 years old and seeing this thing taken away from you. For them it was very traumatic. The best screening in the world was at the Hill City high school auditorium—just a couple hundred people. It was a moving experience just to see people react afterwards.

BROWN: The Field Museum in Chicago bought Sue at auction for $7 million. It seems rather lucky that they ended up being the highest bidder rather than a private collector.

MILLER: There’s a big controversy in paleontology here in the U.S.—the commercialism of paleontology. A lot of the academic community, even after Sue, think that museums shouldn’t spend millions of dollars on fossils. One could argue that Sue has attracted millions of visitors, which has brought so much revenue to the Field Museum. A lot of people on the academic side have attacked our film, and one of the arguments is that instead of museums spending millions of dollars on these fossils, they could fund our research for years and years and years. [But] that’s just a fundamental lack of understanding of how the system works. When Sue was sold, it wasn’t purchased by the Field Museum, it was purchased by corporations—the University of California school system, the [Walt] Disney Corporation. It’s corporate sponsorships that buy these things and donate them to museums to benefit the public. The Field Museum is actually a private institution—it’s not public—but Sotheby’s gave American museums three years to pay for the dinosaur and everyone else had to pay upfront. That automatically weeds out a ton of people. In fact, the top three bidders were American institutions. In my book, Sotheby’s did a really great job, they’re heroes, they saved the dinosaur. The media really blows up every time there’s a big dinosaur auction: “It’s going to get locked in some basement somewhere in some foreign country!” [But] there haven’t been any cases that I know of where that’s happened to any scientifically important specimen; they are always in museums or donated to the public.

BROWN: What if it had been sold to a museum outside of the U.S.—it’s still on public display, but should it stay in its country of origin? There is constant debate about whether museums like The British Museum in London should return treasures discovered by British archeologists abroad.

MILLER: The academic community, particularly here in the U.S., thinks that fossils, wherever they’re found, should stay in that country. We had a famous case where a million-dollar Tarbosaurus, a little cousin of the T. rex found in Mongolia, was auctioned off here in Manhattan. You can’t take anything out of Mongolia, so they seized it, put it in a storage facility in Queens, and the Mongolian president came and repatriated it back to Mongolia and the guy’s going to jail. A lot of the commercial guys, Pete Larson included, feel that there shouldn’t be boundaries where we draw our human boundaries. In fact, it’s a good thing to disperse fossils; just like artwork, they are tangible goods that can be bought and sold. We saw in some of the world wars, a force invades, destroys an entire city, and so much artwork is lost. In World War II, when the Nazi came to invade in France, a lot of artwork was [already] dispersed throughout the world so we didn’t lose everything. That’s kind of the thinking for the commercial guys.

BROWN: Were there any specific scenes in the film that you resisted cutting until the very last minute?

MILLER: Yes. It was very important to me to tell the Indian side of the story. I’m part Cherokee, so I really wanted get into the Native American part of it—and they do not like to be called Native Americans up there, they like to be called Indians. We interviewed a Lakota medicine man by the name of Vincent Black Feather, a spiritual leader and elder. It took us a long time to track him down and he had actually came to Peter’s trailer—Peter lived in a trailer house outside the Institute—and performed a ceremony there. His interpretation from the spirit world was that Peter was to be Sue’s protector in this lifetime and he should fight for her and do everything he can to get her back. That went against a lot of what the natives up there [believed], both on the Pine Ridge reservation, where Vincent’s from, and the Standing Rock Reservation. I talked to a lot of people on the reservations and at the Bureau of Indian Affairs that were around during the time. They were really gracious to give me interviews—they wouldn’t be on camera, but they were very open to phone interviews. They all thought that the dinosaur should remain where it was found except for Vincent. We went to Pine Ridge Reservation with Vincent’s invitation, we interviewed him, and we actually reenacted his entire ceremony—we got some people together and shot it and it stayed in the film until a couple of weeks before Sundance. One time I had a four-hour cut of the film, but being an editor, I understand you have got to get it down. It will be in the “deleted scenes.”

BROWN: Is Sue actually a female T. rex?

MILLER: There’s a big controversy over the sexual dimorphism of T. rexes. The larger ones, they think, are female and the smaller, more docile ones are male. It’s a whole niche part of vertebrate paleontology to just study what sex is. The current thinking is Sue, yes, is a female and they just got lucky. At one point, five or six years ago, they thought it was a boy, which was funny, “A Boy Named Sue” from the Johnny Cash song.

BROWN: In your opinion, which museum has the best dinosaur collection? I remember going to the Natural History Museum in London. They have a huge, plaster T. rex in the entrance hall, and, until watching this film, I took for granted that their collection must be one of the best.

MILLER: There are two. I’m not just saying this because we did a film on it, but the Black Hills Institute is incredible. The big museum that they always wanted in the movie never happened—still hasn’t happened—so they did the second best thing, which is to put it in the high school auditorium they’re working out of. The two best T. rex specimens ever found are in there, and you can go right up and touch real dinosaurs. Usually when you go to museums, there are casts or replicas. These are all real. My second favorite place, and I go there all the time, is the American Museum of Natural History [in New York]. Some of my personal scientific heroes, their collections are in there, and I just think the guys over there—Carl Mehling, the manager, and Mark Norell, the head curator over there—do a phenomenal job. I like London too.

DINOSAUR 13 IS CURRENTLY PLAYING AT SELECT THEATRES IN NEW YORK AND AVAILABLE VIA VOD.