Crew members explain why Spice World is still so weird, 20 years on

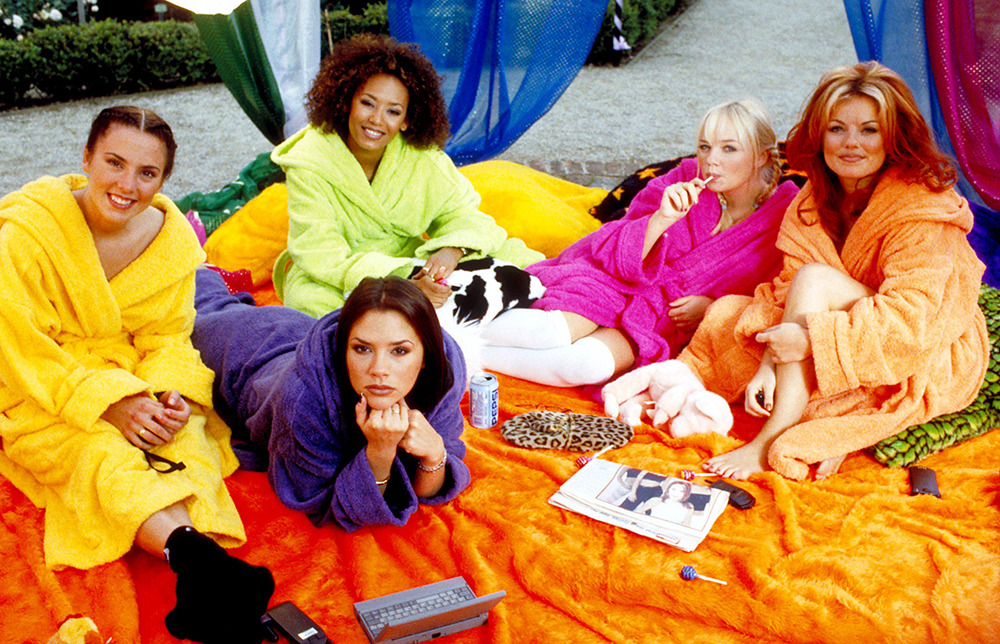

IMAGE COURTESY OF COLUMBIA PICTURES.

Turn on Spice World today, and I promise it will confound you. So many things about the movie don’t make sense. So many things defy the basic rules of narrative, with characters left unexplained and subplots unresolved—but that’s what makes it so captivating and fun. How exactly did this poppy, cinematic romp get made? It’s one of the greatest mysteries of pop culture, and one that, on the occasion of the movie’s 20th anniversary, I’m determined to resolve.

As pointed out on the podcast How Did This Get Made?, Spice World got away with ignoring the most basic tenets of moviemaking and screenwriting. Spice World has no real plot, and no end goal—there’s no real story arc at all, for that matter. The girls pinball from place to place, studio to studio, and rehearsal to rehearsal, each one suited up in her respective coat of character armor. Then, with 10 minutes to go in the movie, the band’s “first live show at the Royal Albert Hall”—fleetingly mentioned in one of the film’s first scenes—becomes the movie’s climactic narrative. Will they or won’t they pull off their first live concert? Thing is, the girls have already performed live only a couple scenes prior—not to mention in the first scene—but this is the grand finale, the moment we’ve all been waiting for. Apparently.

Then, there’s the Spice Bus—which, while certainly a sight to impress even Austin Powers, tricked-out with fairytale ’90s-era gadgets and toys—is also about 12 times the absolute maximum size that any bus interior could feasibly be. It’s a full-on dreamscape, and one that production designer Grenville Horner remembers fondly. “The Spice Bus was fantastic,” he told me over the phone. “It was just fun. You totally invent it; it’s not like anything you’ve ever come across.”

One bone I’d like to pick with the writer and (late) director, Bob Spiers: revisiting the Spice Girls now, I realized just how funny they all truly are in real life. Yet somehow, not a trace of this makes it into the movie. As Roger Ebert wrote in his 1998 review (he gave the film half a star out of a potential five), “[The Girls] occupy ‘Spice World’ as if they were watching it … so detached.” Watch Spice World, and the girls on screen seem like hollow, mechanical versions of themselves. You’d have to read Chris Heath’s 1997 Rolling Stone feature on the group to find out that, say, Sporty Spice ate cat food as a kid, that Mel B liked to tie her hair back with her dirty underwear, and that Posh described her period as “Niagara Falls, I am.”

Oh, what else? How about the creepy paparazzo, who—aside from the fact that his storyline is never resolved—manages to not only fit through an average-sized toilet drain but to somehow figure out the exact pipe that leads to the random mansion that the Spice Girls are currently sleeping in.

And finally, the assless chaps. Let me paint a picture for you: the girls are performing “Leader of The Gang,” with hunky men as backup dancers, who, in an inexplicable turn of events, spin around at the end of the performance to reveal that the chaps they’re wearing are, in fact, assless. If this seems like a nonsensical part of the movie, according to costume designer Kate Carin, that’s because it is. “I suggested doing [the assless chaps] as a bit of a joke to one of the producers,” she told me. “And when he didn’t bat an eyelid I ran with it.”

When I first saw Spice World in 1998 my feelings were very positive. I remember laughing—like, a lot. I remember having a deep, deep respect for the film. And yeah, sure, I was 10 years old, but I wasn’t a goddamn gerbil. By then, I was a devoted fan and follower of South Park. Yet the reason I, and so many others my age, walked out of the movie with a shit-eating grin is due, at least in part, to celebrity worship. It’s the same reason I was blown away by the performances in Crossroads when I attended the premiere in New York. The Spice Girls were British. They were cool. They were provocative and rebellious. In ’98, I would have shimmied on over to London and straight into the Thames if the Spice Girls asked me to.

What’s more, there was no social media back then, as Heath makes abundantly clear in his Rolling Stone feature, when he recalls Mel B pointing to computer monitors and saying, “I want an internet. Can I have one of these?”—and most girls ages eight to 13 did not have particularly high standards when it came to getting a peek at celebrities’ personal lives. I was thrilled to get an alleged portrayal of the real Spice Girls, off-stage. I was content in my willful disregard of the fact that this was, after all, a movie with sets and a script and an alien scene.

It’s a rare breed of movie; as Peter Scheer, host of How Did This Get Made? explains, “Not all bad movies are entertaining. To be worthwhile, they require a sense that someone was actually trying.”

If there’s one thing I could take away from my conversations with the movie’s production designer, casting directors, and costume designer, it’s that these guys cared. Read up on Spice World and you’ll learn that the “Spice Force Five” is apparently based on a fictional TV pilot from Pulp Fiction [1994] and that Elvis Costello played the bartender who got about 45 seconds of screen time. Do some more digging and you’ll learn that there are scenes that reference Nightmare on Elm Street [1984] and Agatha Christie’s fictional character, Hercule Poirot. Like any solid cult film, Spice World is teeming with eerie backstories; jokes about Princess Diana and Gianni Versace had to be cut from the script at the last minute because of their untimely deaths. So too was English glam rock singer Gary Glitter’s scene cut from the movie—this, however, owing to his court trial over child pornography charges.

Spice World certainly does not have the best reputation among film buffs, but it also never purported to be something it’s not. Before the movie came out, Heath asked Mel B why they decided to make a movie when there are “far more terrible pop-star films than good ones.” “Because,” she responds, after sticking a bread roll down her shirt, “I’ve got a third tit.” And therein lies the genius of Spice World and the marketing around it. The movie has a blast without taking itself too seriously. It’s because it’s so inexplicably brainless that it’s also so fascinating and engrossing. A movie so bad that—dare I say it—it’s actually quite good.