Paris’s Cinémathèque Française Sits Still

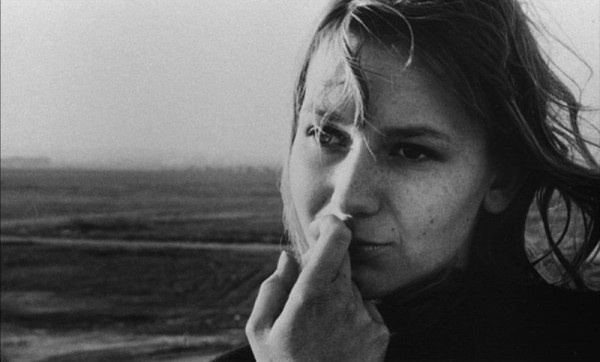

La Jetee

This week, as Parisians return from their August holidays and businesses reopen around the city, one of Paris’ most dynamic cultural institutions will return as well. Henri Langlois started the Cinémathèque Française in 1934 as one of the first film archives. Langlois collected everything: classic Hollywood and European cinema, genre pictures, obscure art film. The frequent screenings he held were a meeting place for French intellectuals in the 50s and 60s; New Wave directors like Truffaut, Godard, Rohmer and Charbrol, known as “les enfants de la Cinémathèque,” were hugely influenced by the Cinémathèque’s eclectic showings.

In the spring of 1968, the French government fired Langlois; the riots that ensued were the beginning of the historic May 1968 protests, and the Cinémathèque has been at the center of French film culture ever since. Fifty years later, it’s still the biggest film archive in the world, and its well-curated, omnivorous programming still attracts a wide cross-section of French society. Punks sit, well-behaved, next to cashmere scarf-wearing Jean-Paul Sartre lookalikes at a Luis Bunuel movie; young professionals and well-dressed grandmothers wait in line to watch 1940s horror flicks. What really matters, though, is that the screen is still big, the sound loud, and the tickets cheap (€6, €5 for those under 26).

The first major series of the fall, “Cinéma Photographié,” which begins today, is organized around the relationship between still photography and cinema. The series, a mix of well-known classics and relatively obscure art films, is typical Cinémathèque fare: smart, but unpretentious and enjoyable. In Jean-Luc Godard’s 1972 Letter to Jane (September 5), one of the first films produced through the Dziga Vertov group (a Marxist film collective Godard founded), Godard and fellow Marxist Jean-Pierre Gorin discuss the aesthetic and political implications of a single photograph of Jane Fonda in Vietnam; both the ambition and the intellectual excitement of Godard’s typically late 60s/early 70s radicalism are in evidence. Antonioni’s 1966 Blow-Up (playing September 6), the most well-known film in the series, follows a photographer as he becomes obsessed with a murder that may or may not be in a photograph he took. Paolo Gioli’s 1992 Filmarilyn, playing (September 16) is a frenetic montage of photographs of Marilyn Monroe which reveals uncanny, repetitive “moving” images by cycling through multiple photographs from the same shoot and altered versions of the same photograph.

But the most interesting film of the series is undoubtedly Chris Marker’s 1962 La Jetée, which opens the festival. Survivors of World War II live in the catacombs beneath Paris’ Palais de Chaillot, where, in 1962, the Cinémathèque was located. The film, a 30-minute ode to the moving image, is a series of beautifully photographed black and white stills, which, strung together, tell the story of a man sent back into the past–into his own memory–to seek help for the survivors of the war. For the man, traveling through time, images “ooze like confessions.” The film’s stills are strangely nostalgic and evocative, flowing together like a dreamed version of the cinema. The single moving-image scene, a 5-second shot of a woman waking up, bursts through this dream with all the quiet power and generous beauty of the cinema made new again. In the basement of the Cinémathèque, then and now, French film argues persuasively that the moving image has a singular and quite real effect on the world.

Cinéma Photographié runs from September 2 through 19th at the Cinémathèque Francaise. The Cinémathèque Francaise is located at 51 rue de Bercy, Paris.