Christian Bale talks Hostiles and transforming into Dick Cheney

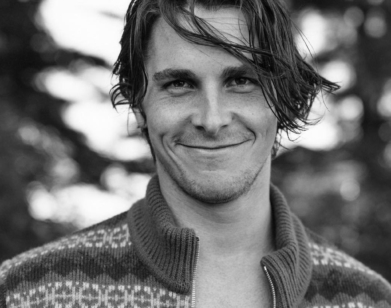

When Christian Bale walked into the room at the Crosby Hotel in Manhattan, he was nearly unrecognizable. The 43-year-old actor, who normally looks every bit the leading man he is, was much rounder—more Penguin than Batman—with a shaved head and bleached eyebrows. His baggy cargo pants and loose-fitting button-up wasn’t so much a fashion statement as it was a practical choice, given the extra 40 pounds he was carrying. Bale’s current transformation—the latest in a career defined by them—was for his role as former Vice President Dick Cheney, in an Adam McKay-directed biopic to be released later this year.

But today, Bale is in town making the latest stop in a media tour for his new movie Hostiles, a brooding Western that sees him starring as Capt. Joseph Blocker, a decorated veteran who is tasked by the president with escorting a dying Cheyenne chief across an expansive and unforgiving landscape so he can be buried on his ancestral land. Blocker has seen his friends massacred at the hands of the Native Americans and harbors a deep racial hatred for people he sees as savages. His resentment at having to complete this mission is palpable. But as Blocker and his men make their way to Montana with the chief and his family, Blocker’s prejudice begins to evaporate as his band of soldiers and the Cheyenne family they’re escorting face down the dangers of the West together.

Hostiles marks the second time Bale has collaborated with director Scott Cooper, following their team-up on the 2013 drama Out of the Furnace. It also marks the second time Bale has starred in a Western following 3:10 to Yuma, where he also played a man tasked with escorting a prisoner (Russell Crowe). When I bring up Bale’s ubiquity in the Western-road-trip-prisoner-escort sub-genre, he sort of agrees with me, and then says that the two movies are “vastly different,” which is where we begin the following conversation.

BARNA: Did you see this film as a revisionist western, as something that was subverting what we might typically associated with the genre?

BALE: I don’t have a great knowledge of film, so I can’t truly say how revisionist this is. People say it reminds them of The Searchers [John Ford’s 1956 film about a Civil War vet on a mission to rescue his niece from the Comanches], and I’ve never seen The Searchers. I would think most directors would say it’s necessary to watch many films with the exception of Werner Herzog—I would expect him to say no, better not to watch any. But as an actor, I don’t feel like it’s necessary to watch a great deal of films. In fact, I think it can lead to imitation and unhealthy competition, which just isn’t needed. And I’ve got kids anyway, so I’m usually watching whatever they want to watch.

But I’ve certainly seen enough Westerns to know it’s not black hat, white hat western—it’s certainly not American propaganda, in terms of good cowboy, bad Indian. It’s a very intelligent cavalry captain who, whilst he does harbor sincere hatred for the character that Wes Studi plays, Yellow Hawk—because he has seen him butcher his own men—he’s intelligent enough to know that Yellow Hawk is defending his culture and way of life. My character is attacking that way of life, and he is perpetrating genocide. So there’s a hatred, but there is equally a respect because he knows he would behave the way Yellow Hawk would if he was in his shoes.

BARNA: Does your character make the right decision at the end of the film?

BALE: It’s an interesting thing, Scott Cooper and I debated that to no end. Having seen the film now, I was arguing for Blocker to just disappear in the crowd. My understanding is that it’s somewhat more akin to The Searchers in the end—I have to go see that. The book that I read that made me think of it was [F. Scott Fitzgerald’s] Tender Is the Night—people who have been so very close and meant everything to each other, and suddenly one of them disappears in the crowd and that’s it, you never see him again. I quite like that notion, however I did recognize that it’s torturously sad for this individual Joseph Blocker, who had been absolutely essential and now had no use in society whatsoever.

However, I felt that it did reflect somewhat the attitudes toward soldiers nowadays, in that so much lip service is paid in gratitude, but actual gratitude and action is fairly limited, and is quite shameful and abysmal in a way that so many victims and families of victims are treated. So I felt like maybe that was realistic. Scott talked about getting on that train and I didn’t know how to do that in honesty, without it feeling like, “Oh, it’s a movie ending!” But I know Scott, and he would never wish for that anyway. So I didn’t really get how to do it until we were really there on the day and it was just the force of so many forces pulling him away from that. Not wanting to get on the train but also knowing that if he doesn’t get on the train, that the connection with this other damaged individual, who he has kept alive, would be lost forever. But there’s a tragedy within the hope in that clearly these are two damaged individuals, we have no idea if outside of him keeping her alive, if there is anything that will sustain any sort of relationship. We’ve shown no hint of a sexual relationship—she has comforted him, which is probably the only comfort he’s ever received in his life. But then there’s also Little Bear. So he’s lost everything and he has these two very damaged individuals who want to see if they can take care of him. But what you’re also witnessing is a soft genocide here, and Scott intended that completely in that you’re now seeing this boy who is dressed in a western suit. I thought that was a wonderful ending because yes, it has hope, but it also raises many questions about the future and the genocide that really continues today without the direct killing, but the genocide of culture.

BARNA: When you’re making a historical film like this, do you look for parallels in the modern world?

BALE: No I don’t, I just look for something that I can get obsessed with. You need that because you’re going to be working on it for months and months, and if it isn’t enough to get you obsessed with, you’re probably going to find and discover all of the answers you needed for filming, and then you end up being bored and boring. But I couldn’t help but notice as we were filming this, it was becoming relevant, and since we’ve stopped filming it’s become ridiculously relevant in the comfort in which so many Americans are expressing hatred for people who are different from themselves, and hopefully that will be short-lived. It’s obviously insanity to do the same thing over and over and expect a different result. And also the notion of, you cannot solve a problem with the same mindset that created that problem, so it’s strange times.

BARNA: You’re notorious for the physical transformations you go through for roles. I can’t sense if you transformed physically to play Blocker, but were there other transformations you went through?

BALE: Well, certainly you have to recognize that these were hardscrabble times, and these were certainly not men who would be rotund. They would be very wiry, strong individuals. We had to be well acquainted with riding horses for 10 hours a day, well acquainted with the guns, et cetera. Learning the Cheyenne, which was very fascinating because I expected that it was going to be a very phonetic teaching, but the chief of the Northern Cheyenne, Chief Phillip, came down and helped me, and he wouldn’t look at me until I learned significant amounts about the cultural life of the Cheyenne. We’ve become very good friends—he’s a very inspirational man, and at that point he began teaching me the language.

BARNA: Does Blocker find redemption at the end of the film, or is a man who has killed so much capable of being redeemed?

BALE: I think it will always remain within him, the question of the lie for him of manifest destiny. He’s questioning his faith because he knows the truth is that he was looking out for business interests and perusing landgraves and enacting genocide, and that will never leave him, and I think his hatred for politicians in that case will be constant. But I do think that he will never know how to really be among people because he’s been so isolated his entire life. Whether he could find comfort in his own soul and mind, I don’t know the answer to that.

BARNA: This film has a great score by Max Richter, and I was wondering if you see scores as helpful amplifiers of your performance?

BALE: It’s great obviously with a good composer. It could be overboard with some films, where you go, “I get it, please, enough.” But what I do, and I had a very long script with Blocker because he says so little, is I do actually tend to write very specific lines, whether he says them or not. Then they’ll be passed in with the lines that he says but there’s what’s going on in his head and what passes and comes out of his mouth. So it’s incredibly elegantly done and helpful in this film to give an indication of what he might be thinking.

BARNA: What can we expect from Cheney, which you just finished making with Adam McKay? I’m assuming that while being a biopic of a very serious and polarizing figure, there will be plenty of comedic elements to it.

BALE: Yes to all of that. It’s not your straightforward biopic, and if it had been I probably would’ve said you really need to go somewhere else. It’s fascinating that it’s taken as much research as I’ve ever had to do for any other film. Adam likes a lot of improvisation, and when you’re playing Mr. Cheney, you need to not only speak in the vernacular that he would speak in, but all the policies that he would be aware of and instances of them, the abbreviations for all of them, and be able to just go with it. So it was very fascinating for me.

BARNA: I think the greatest compliment you can pay directors is working with them again, and you’ve done it with Scott, you’ve done it with Adam, and so on. Do you enjoy that familiarity and shorthand with someone?

BALE: Yeah! I’ve done that with Scott, with Adam, with David O. Russell, with Chris Nolan, Terry Malick, Michael Mann and I plan on doing something else. So yes, you get a shorthand of language and understanding of that. And there’s many directors as well, who we both would mutually agree we never want to work together again—it just didn’t work.

HOSTILES IS OUT IN THEATERS JANUARY 26, 2017.