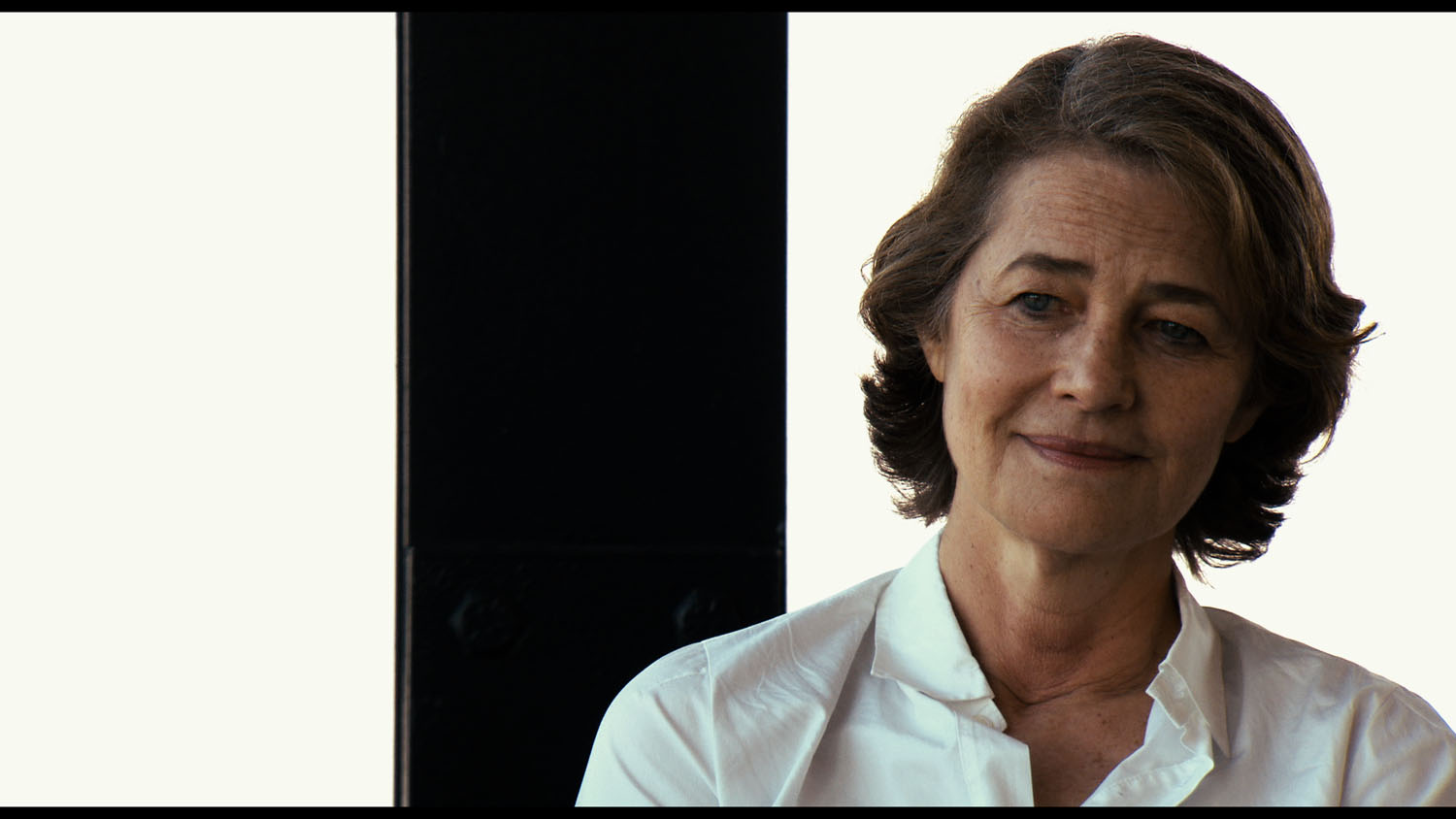

Charlotte Rampling Holds a Gaze

From the opening shot—a close-up of the actress turning toward the camera and looking directly at the audience, her look beaming through the screen—it’s clear that Charlotte Rampling: The Look is not a normal puff-piece documentary. The film, while ostensibly about the famous actress, has a much larger vision in mind. Its director, Angelina Maccarone, structures the film with nine separate chapters, each featuring Rampling and a friend (including the author Paul Auster, the artist Juergen Teller, and the poet Frederick Seidel) examining their thoughts on specific, universal subjects such as age, beauty, desire, and death.

Interview spoke with Rampling, who, it must be said, displayed none of her famously chilly demeanor, about the being exposed on camera, collaborating with artists, and not being listened to.

CRAIG HUBERT: What was your first thought when you were approached about being the subject of a documentary?

CHARLOTTE RAMPLING: Well, it took a while for anything to happen, really, because it was not something I really wanted to do. As you saw, if you remember what I said about exposure in the film, it’s not something that I necessarily go towards. But in the end, it became something I just couldn’t get out of, and then we found a way to make a concept of it so it wasn’t a documentary where people were talking about me, but that I was just talking about things, and then it could be illustrated by my work. So it became a format which was suitable to me.

HUBERT: Do you normally feel exposed when making a film? Is it something you struggle with?

RAMPLING: Yeah, I struggle with it, but it’s so much part of everything—that’s what I do, that’s the game, that’s the pitch. We expose ourselves, and so we deal with it.

HUBERT: Is there something about specific directors that make you more comfortable or less exposed?

RAMPLING: Yeah, absolutely. You meet them first, you somehow—with this particular film, it was Angelina’s gentle approach, and she made me understand that something could come out that was interesting. She actually was able to make me a little more confident in myself, and not being very confident in herself, so we were actually two not-confident people in themselves making each other more confident. [laughs]

HUBERT: A normal documentary of a well-known person tends to want to demystify, revealing some truth the public doesn’t know. This film is based around conversations, and specifically asking questions and not necessarily giving answers. Was this a strategy from the beginning?

RAMPLING: I imagined there could be a way of communicating like that—communicating without exposing yourself, and saying, “Here I am, I’ve done this, here are these people talking about me”—but exposing the essence of a person, which is me, through conversations and asking questions, not actually answering questions, but putting things forward.

HUBERT: In the film, you talk about your public image. Was the film a conscious effort to reverse that image, to open up?

RAMPLING: No, because that’s how I am. That’s how I always have been. But I know that I also very much am seen as something else, because I’m a private person. So I can be seen as not being very communicative, or rather mysterious, or distant, or rather cold—all those things. Yeah, I know I can give off that impression. So I am that, too.

HUBERT: Was that public image self-created?

RAMPLING: No, because it is me. It’s my way of protecting myself.

HUBERT: I ask because there is an interesting part of the film where you talk about a negative review Pauline Kael gave The Night Porter, and how it affected you. It’s very common nowadays for an actor to say, “I don’t read reviews.”

RAMPLING: Yeah, I think possibly people will say they don’t read their reviews because if you do that, once or twice, you don’t really do that again. It’s too violent, someone actually trashing you. Politicians are having that all the time. I’m quite sure they wouldn’t survive if they read all the stuff written about them.

HUBERT: In the film, you talk with the photographer Peter Lindbergh about the merger between artist and subject. Do you see this documentary as a merger between you and the director?

RAMPLING: Yeah, I would hope so, because it’s something we need when we’re doing something creative with someone else. You either stay in your camp, and he stays in his, or there’s a kind of melting of the—for me, it’s actually a handing over. I give myself over to the person, because I think it’s much more exciting and fun if you do, and it’s more dangerous, and you risk more, because then you think, “Oh, well maybe they’re going to do something of me or with me, that’s not going to be”—and then I say to myself, “What on earth can happen? We’re only making pictures, come on.” It’s a much more exciting way of working. That’s how I do work with directors and photographers.

HUBERT: That’s very risky. Have you ever been disappointed by handing yourself over like that?

RAMPLING: The only other alternative is to have control of what you want to do, and do it in your own way. Is that interesting? I don’t know. I don’t find my way very interesting because I’m a collaborator; I collaborate with people in my work. It’s not just me.

HUBERT: Throughout the film, you are often seen holding a camera, taking pictures, and later on working in your studio painting. As someone who is actively looked at, you’re constantly looking, reversing that role. When did you start these other artistic practices outside of acting?

RAMPLING: A long time ago, for that very reason. With photography, it was very much—because cameras then, you held them up to your face, so you were hiding behind them too, and I loved that whole thing of suddenly just be private, behind, and see through a little tunnel, an image, a person. So I started that a long time ago, when I was about 30 or something. And I was quite good, and was pleased with the stuff I did, a lot of black-and-white work; and then painting for the same reasons, although painting you can’t walk around with. I have a studio in Paris and I do a lot of work there.

HUBERT: The subjects in the film, aside from being friends, are also artists. There are no real actors in the film.

RAMPLING: No, there isn’t. I wanted close friends, really—collaborators. I know a lot of actors, obviously, and I had one very close friend, a girl, who has died, that was an actress. Close girlfriends I don’t have necessarily, as an actress. Perhaps there is a thing of competition there, you know, when you’re doing the same things, and you’re the same age. I could be with younger actors, but woman of my age probably—there is and there isn’t, one doesn’t like to think of it, but I think there is a sense of competition. Which is good, also.

HUBERT: I thought it was maybe because actors are constantly looked at.

RAMPLING: The main reason, exactly, is that we’re too clever. I didn’t want a clever actor. I didn’t want somebody have the right answers. I wanted somebody who was a bit shy, and had more difficulty.

HUBERT: Some of the conversations resemble sparring matches—one is actually held in a boxing ring—with a fair amount of tension between you and the person talking.

RAMPLING: I didn’t know who we’d be talking with, because these people don’t normally talk on camera. I said, “We’re going to be talking about a subject, would you talk?” I was quite shy, even, about asking them. My dear friend Fred Seidel, the poet, he was the first one who said yes because he loved the idea, but in the end he said, “I don’t want to be seen. I’m a poet. I write words.” I said, “What are we going to do?” Well, it worked out beautifully, but I could understand that. There are always going to be problems like that with people who are not used to this, because it’s a bit—it’s not an easy thing to do. But what I said to everybody was that we just do one take, just a long stream-of-consciousness, just talking about this, talking about that, around the subject. We didn’t go back, do anything more. Each time it was one conversation.

HUBERT: So many of the artists you talk to in the film never get a chance to open up like this in a film—

RAMPLING: Even Juergen Teller, who you’d think with the work that he does—but artists are very shy people. Peter Lindbergh was unbelievably nervous! It was so funny—the greatest photographer on Earth, with all those most beautiful women in the world that he has photographed, and he’s like a trembling little boy!

HUBERT: At the end of the film, you talk about the joy of finally be listened to without interruption.

RAMPLING: [laughs]

HUBERT: Have you always felt, as an actor, that you are not listened to?

RAMPLING: I’ve always felt as a human being I’m never heard. Actually, that was the first bit we did. People are always—even people I live with—saying, “What are you going on about, not being heard?” I don’t know. [laughs]

HUBERT: Well, so much is said in the film. Do you feel like you finally have been heard?

RAMPLING: Well, it’s only starting now.

CHARLOTTE RAMPLING: THE LOOK IS OUT NOW IN LIMITED RELEASE. RAMPLING ALSO APPEARS IN MELANCHOLIA, WHICH IS OUT NOW ON VIDEO ON DEMAND AND WILL BE RELEASED IN NEW YORK AND LOS ANGELES NOVEMBER 11.