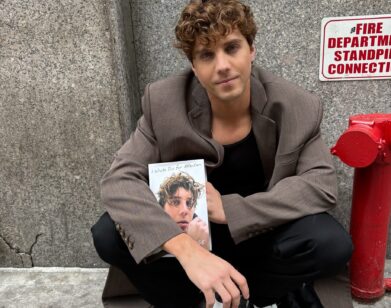

Exclusive Trailer Preview: ‘Blinders,’ a Short Film by Jacob Brown

What happens when appreciation gives way to attraction, and attraction to physical expression? In Blinders, starring Luke Worrall, Nathaniel Brown, and Byrdie Bell, a young man stumbles into another man’s arms, leaving his girlfriend in the lurch.

The short film’s trailer, soundtracked by Home Covers’ “The Flame,” opens with an illuminated, androgynous Worrall nude under white sheets. “The point I find interesting is that with many models, their beauty transcends handsomeness or prettiness or sexual attraction,” says writer-director Jacob Brown, an editor at the New York Times and himself a former male model. Regardless of whether or not the couple reunites, the short begs the question: who is the primary victim of beauty—the possessor or the beholder? Interview asks Brown these tough questions and more:

AMANDA DUBERMAN: You were yourself a male model. I imagine you are specifically attuned to the utility, and indeed the consequences, of beauty and youth. How does Blinders explore this theme?

JACOB BROWN: In general there is a surprising tension in society when it comes to how beauty is viewed. On the one hand, beauty is commodified and assigned a very high value: sex sells. On the other hand, or perhaps because it is commodified, human beauty is considered of low aesthetic or spiritual importance, unlike say beauty in art or nature. This has not always been the case. Certainly in the religious art of the renaissance, and in the actual religion of classical times, human beauty was of a high aesthetic value and spiritual importance. If you believe in God, then it would have been His hand that created the face of the character played by Luke Worrall in Blinders. And indeed the point I find interesting is that with many models, their beauty transcends handsomeness or prettiness or sexual attraction: regardless of whether you want to sleep with this person, you want to stare at his or her face like you’d stare at a piece of fine art hanging on the wall of a museum or gallery.

When we were filming Blinders my cinematographer Bobby Bukowski said to me at one point that Luke Worrall (who at the time was lying in the sun, his skin and hair glowing bright white) looks like a different species. When he said that, I remember thinking to myself, “Yes, exactly.”

DUBERMAN: What is the significance of the film’s title? “Blinders,” to the extent that they prohibit what we can see, can spare us from pain or prevent us from flourishing. Does the film promote the idea that tunnel vision is a blessing, or a curse?

BROWN: A lot of people move to cities like New York with an idea in their head that they will become something, or join some world they imagine exists. But they don’t really know the details behind what they’ve imagined. They end up kind of floating in and out of various aspects of their lives, including their romantic relationships, sometimes to the point of floating back and forth between partners of either sex. So they have their eyes on this sort of mystical goal in front of them, but they can’t really see what’s going on in their life as they chase it. A bit like wearing blinders. In the short, Nathaniel Brown’s character has a monologue about this topic, and in delivering it and without realizing he is doing so, he seduces or is seduced by Luke Worrall’s character.

DUBERMAN: The trailer leaves some ambiguity about who might be the victim of Worrall’s beauty—the young couple who betray each other, or Worrall himself if the couple reunites and he is left alone. Who do you think the primary victim of beauty is—the possessor or the beholder?

BROWN: To be honest, I don’t think Blinders answers this question. But it asks it. It’s ambiguous just as in life you may (or may not) know how you feel or have been made to feel about things, but almost never know how those around you feel. I have a feature film in the works now that is very loosely related to Blinders (in essence it takes place in the same world and uses the same visual grammar). This film will very much explore, and roll around in the tragedy of beauty, particularly as a certain breed of male model—the skinnier, punkier breed—experiences it. As it is a feature, it is longer, and get’s much more into the life narrative of the characters, how they end up in New York, what they want, what being a male model-objectified and subject to the male gaze as typically only women are-does to their psychology and sexuality.

DUBERMAN: Do you see Blinders as an LGBT film? Is that genre problematic?

BROWN: Perhaps. The character played by Byrdie Bell is a straight woman in a relationship with a man, a man whom I would guess is primarily heterosexual. I don’t think she knows quite what is happening in his head, but she knows something is going on. Women’s intuition or what have you. I think plenty of straight women can relate to that. But in the end I don’t really care. I can only tell the stories that interest me and excite me. In the feature I am working on, the main character does have an experimentation. But it’s a small moment. And that is way more interesting to me. A totally straight dude from a small town who suddenly finds himself in a world where he might have a brief relationship that doesn’t necessarily conform to how he views himself.

FOR MORE ON JACOB BROWN, AND TO LEARN ABOUT NEW SCREENINGS OF BLINDERS, VISIT HIS WEBSITE.