Over the Rainbow and Into a Trip

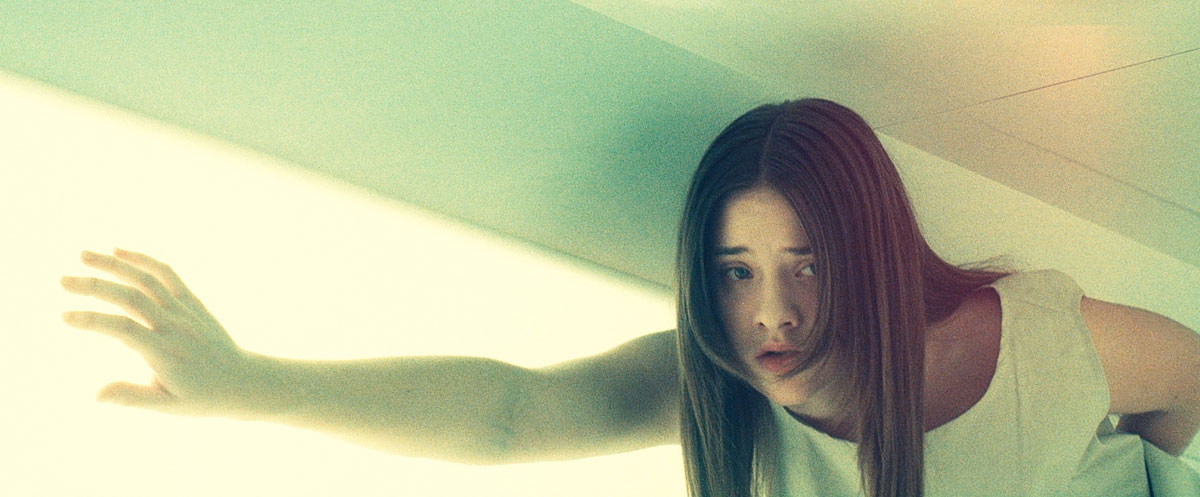

FILM STILL COURTESY OF NORM LI

One of the pleasures of the Tribeca Film Festival is discovering a hidden gem among the first-time filmmakers. Panos Cosmatos is a new visionary talent, whose extraordinary feature debut, Beyond the Black Rainbow, is even more remarkable because its sleek, ultra-futuristic sci-fi vision was executed not with groundbreaking digital technology but with old-school, 35-mm film. Even more amazing is that the 37-year-old filmmaker did not attend film school or art school. The son of George P. Cosmatos, who directed “popcorn movies, blockbusters” (Cobra, Tombstone), he is almost entirely self-taught.

Cosmatos takes a horror plot that we’ve seen in countless incarnations—the evil doctor controlling a young beauty as she struggles to escape—and infuses it with a color-drenched visual style. In particular, a sequence depicting an LSD trip is astonishing in both the conceptualization and execution of its hallucinatory, amorphic imagery.

George Lucas’ 1971 film THX 1138 is something of an antecedent to Beyond the Black Rainbow, which is a dystopia set in 1983. But a more significant influence would be Cosmatos’ mother, whom he says is an artist “who made very bizarre, abstract, three-dimensional, haunted kinds of pieces.”

LORRAINE CWELICH: How did you learn the technology used to execute the film’s imagery?

PANOS COSMATOS: It was shot on an old 35 mm camera with lenses from the 1970s. There’s a very specific look I wanted, to give it a slightly faded look. I’ve been watching films my whole life and am completely obsessed with them. I taught myself filmmaking on my own. All the specific effects in the movie are analog. They’re done in-camera.

CWELICH: How would you describe this film to an audience?

COSMATOS: An experience, a discovery. Just let it wash over you as it unfolds.

CWELICH: Is it a metaphor for your childhood?

COSMATOS: Only in the most abstract, fragmented way. Memories and feelings from my childhood, put them into context with my current state of mind. I wrote the film in a sort of steam-of consciousness, instinctual way.

CWELICH: What was the prevailing emotion you remember from 1983?

COSMATOS: We moved around a lot when I was younger. I never really felt at home until we moved to Canada, but even then, I always felt strangely out of place and alien.

CWELICH: What music were you listening to in 1983?

COSMATOS: When I was a kid, I was obsessed with heavy metal, Van Halen, Mötley Crüe. The older I got, my tastes widened. I always felt an attraction to the attitudes of punk; also punk filmmakers, like Richard Kern.

CWELICH: What filmmakers were you influenced by?

COSMATOS: The two films that crystallized for me that I wanted to make films were Scorsese’s After Hours and Sam Raimi’s Evil Dead II, when they came out in close proximity to each other.

CWELICH: After Hours is a great film. Talking about being an alien in a strange world—Griffin Dunne in downtown New York at night.

COSMATOS: [laughs] To my perspective, growing up in the suburbs, that was a bizarre world. I could not relate to it whatsoever—it just seemed like an insane maze. To a New Yorker, it was a documentary! I think it was the brazenness of the filmmaking in those two films that showed me in a very explicit way what a director can do, how he can express himself through camera movements and framing and energy.

CWELICH: Can you talk about the very precise art design?

COSMATOS: After I finished the script, I hired a storyboard artist and we storyboarded the entire film. Design-wise, I wanted it to hearken a bit to action figures in play sets from the ’70s.

CWELICH: Talk a bit about the painterly use of color.

COSMATOS: Colors in films are emotions. I felt that sometimes filmmakers are afraid to use bright, vibrant colors, so I wanted to go in the opposite direction and completely saturate it with color.

CWELICH: The early part of the acid trip, where the heads are molting and organically evolving into others shapes and colors—how did you visualize it?

COSMATOS: The stylization of the acid trip—there’s so many clichéd images associated with trips in film. I wanted to go in the opposite direction, so the reference point was to make it almost mythical. In Jean-Luc Godard’s Contempt, there’s a film-within-a-film of Ulysses, and they refer to a scene as “the battle of the gods.” It’s only shots of heads rotating in front of a blue background, so that was sort of the inspiration for having the acid trip be more sculptural.

CWELICH: How did you execute that sequence, without using computers?

COSMATOS: Back in the day, all special effects were done using practical methods. I used to read Cinefex magazine [which is devoted to movie visual effects] obsessively, so I just built up a lot of information in my mind about how special effects were done. A lot of those layers in those sequences were done by putting paint into salt water, and then we blended them in post-production. I also just absorbed a lot of stuff by osmosis over time. Computers have their place; I just think they should be used as an enhancement to actual analog, live-action elements.

CWELICH: What artists currently interest you, across the arts?

COSMATOS: I’ve gotten into [novelist] Bret Easton Ellis lately. As far as contemporary films, I liked Sofia Coppola’s latest film, Somewhere, a lot. I found it incredibly refreshing and beautiful. But it’s funny; I don’t lately make a point of keeping up with everything that comes out. I kind of feel like it distracts me from my own creativity. I mostly watch older things right now. Musically, I like a lot of obscure soundtracks from Z-grade films from the ’70s and ’80s. I also like grindcore, which is a really extreme form of heavy metal. I find it really relaxing.

BEYOND THE BLACK RAINBOW SCREENS TOMORROW AND SATURDAY AT THE AMC LOEWS VILLAGE 7 AS PART OF THE TRIBECA FILM FESTIVAL. FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT THE FESTIVAL’S WEBSITE.