The New King of the Outback

STILL FROM ANIMAL KINGDOM

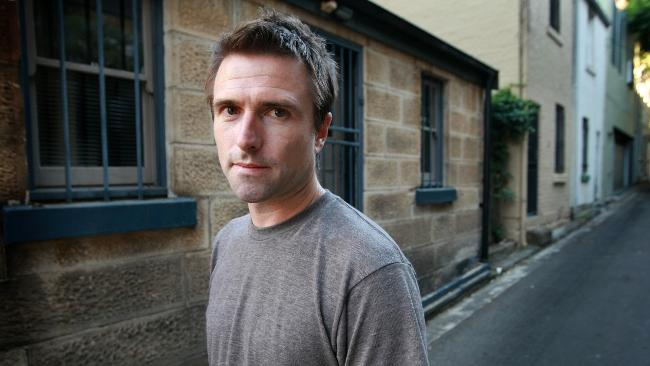

PHOTO BY TONY MOTT; COURTESY OF SONY PICTURES CLASSICS

Australian filmmaker David Michôd’s feature debut, Animal Kingdom, already a success the world over–it won the Grand Jury Prize for World Cinema at the Sundance Film Festival this year—is landing Stateside this Friday. The film, which follows 17-year-old Joshua Cody (James Frecheville) as he ventures into the dark heart of his criminal family, is as visually and aurally arresting as it is refreshingly retro (think ’70s Scorsese, but Down Under); it may also be the announcement of a new generation of young Aussies ready to make an international impression. We sat down with Michôd to talk about creating a universe, why he goes to the movies, and how it feels to be under the microscope.

AUSTIN BERNHARDT: How has your life changed, on a day-to-day basis, since the success of Animal Kingdom?

DAVID MICHÔD: Getting used to attention is always challenging—feeling like I can say no to people, feeling like I can ask for things because so much more is being asked of me. It’s required me to be more assertive than I naturally am.

BERNHARDT: In Animal Kingdom, you were working with some of the biggest names in Australian cinema. Did you ever feel intimidated working with people who were already very well established in the filmmaking world?

MICHÔD: Yeah, a little bit during rehearsal. That first day of rehearsal is what’s intimidating, but what you work out is that actors need directors. They’re not sitting around the table with a clear idea of the film they’re going to make with. They want a director’s guidance because they want to be able to lose themselves in their characters and lose themselves in the universe of the film knowing that someone has a clear idea of what that universe is.

BERNHARDT: Do you think your work in film journalism has informed your style or your approach to filmmaking at all?

MICHÔD: I think it’s made me more aware than filmmakers often are of the importance of the back end of the process, that even when you’re done editing, the process continues for months into marketing, publicity, distribution. Your film isn’t just what you’ve made; it’s how it is represented in the world.

BERNHARDT: The movie is full of these strange moments where you’re not sure if you’re supposed to laugh.

MICHÔD: Yeah, there’s nothing more rewarding for me than seeing a film and feeling surprised-and that doesn’t necessarily mean a boogieman appearing from behind a door. But to be presented with something that seems familiar, and to suddenly find it unusual, is why I love going to the movies.

BERNHARDT: One of the things I loved about the movie was seeing all of this terrible energy compressed into this one typically suburban house.

MICHÔD: That’s one of the reasons I’m most excited about the film releasing in the States, because Australia has more in common with the United States than it does with any other country in the world. We have similar cultural backgrounds that have, over the past couple of centuries, been mashed up into these great multicultural melting pots, and in a sense, one of the things most gratifying for me at Sundance was how that world so particular to Melbourne is so universal, especially to an American audience.

BERNHARDT: Do you think there’s a particular style that’s developing among this new crop of young Australian directors?

MICHÔD: I’m not entirely sure. I think what we might be seeing at the moment is a new generation of filmmakers with a greater willingness to embrace genre in all different ways.

BERNHARDT: Is there a genre that you’re drawn to next?

MICHÔD: Not really. As much as my interests are varied, it feels like the sensible thing to do is to not stray too far from where I’ve just been, in order to consolidate my voice. Having said that, I don’t just want to go and make another crime film. These are the kinds of questions I’m having to ask myself under the microscope–what to do next, where to do it, and on what scale.