DIRECTOR

Andrew Bujalski and Whit Stillman on Harvard, Hollywood and “Harmful Flattery”

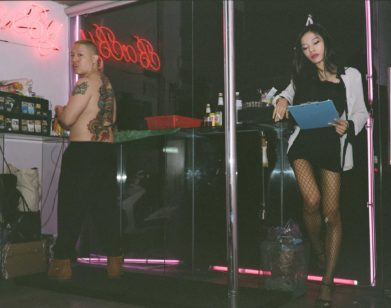

Who is Andrew Bujalski? Magnolia Pictures’ release of his new film There There gave me the chance to find out. I first saw the Bujalski name on a poster for his debut film, Funny Ha Ha. Resentment and jealousy are my usual responses to newly acclaimed directorial talent, but Andrew’s arrival was good news. Word of the microbudget indie film movement he partly started—said to feature wall-to-wall “mumbling” talk—helped get my film Damsels in Distress (2012) off the ground by convincing the backers that with so-called “Mumblecore” talent we could make the film cheaply, while promising a lusher look and clearer diction. Greta Gerwig, who would star, made her name playing opposite Andrew in Joe Swanberg’s Hanna Takes the Stairs (2007). Twenty-five years separated the Harvard Andrew and I attended. He knew early on what he was about and got into the film program formerly (aptly) known as “Vis Stud”—the Department of Visual Studies. This mecca of “cinéma vérité” was well portrayed in Alex Olch’s The Windmill Movie (2008), but Andrew wonderfully transcended vérité’s tedious and stultifying doctrines in his delightful 2018 Regina Hall showpiece, Support the Girls, still the best introduction to his cinema. His adventurous Covid project, There There, now on screen, offers indie film mavens the chance to get up close and personal with Lilli Taylor as well as standout sequences with Molly Gordon and Bujalski original Annie LaGanja. Andrew and I got together on Zoom six time zones apart to discuss filmmaking aesthetics, fake Texas vs. real Texas and, of course, Rick Linklater. — WHIT STILLMAN

———

Whit Stillman: Hello. Oh my gosh, Andrew. You’re going gray. Welcome to the club.

Andrew Bujalski: Yeah. Well, I’m fine with that. It’s the bald spot that I’m not happy with.

Stillman: Well, it’s very good to meet you, Andrew. As you probably know, I’m a huge admirer of Support the Girls.

Bujalski: I’m so, so honored by that. Thank you so much. And it’s so nice to digitally meet you here.

Stillman: It’s good to meet you. You’re in Austin, or on the East Coast?

Bujalski: Well, I live in Austin, but I’m coming to you live from Brooklyn at the moment. I’m in town because we opened There There at the IFC Center.

Stillman: Well I’m really glad that I finally got to see Computer Chess this weekend. It’s wonderful. It’s really extraordinary. And Gerald Peary is a terrific actor. By gosh, is he good in it. Was he at Harvard when you were there?

Bujalski: Maybe just after. I think there was a year where I was still hanging around, so I probably would have encountered him there. With my first movie, I made it and then I had no idea what to do with it. I remember holding a 16 millimeter print and hugging it to my chest and thinking, “Oh my god, I’ve done what I set out to do, but I have no idea how to get it seen.” And Gerry was the first person ever to run it. He programmed it for a local Boston movie series at the Coolidge Corner. So he’s always been close to my heart for that reason.

Stillman: I read somewhere that Chantal Akerman was one of your teachers?

Bujalski: I was very lucky to be there the one year that she taught there, my senior year. She was my thesis advisor. I’ve always felt like I’ve claimed no particular aesthetic influence from her because her voice is so entirely her own. But as a kid from the suburbs, from Newton, Massachusetts, to be in the presence of an artist that serious. I’ve never known a more committed artist in any discipline. And she was very funny. That was another great lesson too. I feel like you can’t be that serious without being funny, and vice versa.

Stillman: Then you dodged a bullet, because that was my gig! She stole it from me. Hal Hartley had been the filmmaker in residence, which was opening up. And I told Gerry, “Hal? I should get that.” Then, for some reason, they preferred Chantal Akerman. Think of what your movies might have been like if I had been your influence and not Chantal Akerman.

Bujalski: I’d be a commercial knockout now.

Stillman: So, there kind of was an ethos of vérité there. And I could never get into anything academically exclusive in college, so I never got to take any of those courses. But I really felt that their whole approach was just so antithetical to what I like, because I detest “vérité.” For me, it’s an ugly word. And that department was imbued with it. I feel cinema is artifice and we should relish the artifice. And for me, what’s cool about Computer Chess is that within sort of the conceit of vérité, you actually have a fabulously artificial production design and mise-en-scene and muffled comedy everywhere. And then in Support the Girls, you have that wonderful sort of Texas bosoms’ version of reality, that has its own aesthetic. Was that inspired by your time in Texas?

Bujalski: Of course, Support the Girls is highly Texan or at least my best version of it. I’m not a native Texan, but I’ve been around enough. It’s also kind of a fake. It is such a mannered thing, anyway. You know, Texas is great about self-mythologizing. It’s not difficult to find lots of fake Texas in real Texas. We thought of it as kind of liminal, inasmuch as that whole movie takes place on highway sides. It’s all transitional space, anyhow.

Stillman: So your trajectory from the Northeast to Austin. Was that just love and marriage, or is there also a sort of filmic path? Because I thought of living in Austin, too. I think everyone did. It was very, very alluring back then in the 90s, before the explosive growth.

Bujalski: So I first moved down there in ’99 when I was a year out of college, and—

Stillman: That quickly?

Bujalski: Yeah, because it seemed fun. I was 22 years old. And I didn’t need a better reason to move somewhere except that it seemed fun.

Stillman: Yeah, yeah.

Bujalski: It was myself and a few roommates and some people who ended up working with me on those first couple movies. We didn’t know what we were doing. We didn’t know anyone, there were no jobs for us. So we just did what young people do and enjoyed ourselves for a year and kind of managed to scrape by.

Stillman: It was already an indie film mecca then, wasn’t it?

Bujalski: Yeah. Certainly, Linklater had such a huge outsize impact on everything film in that town. I don’t know that I would have heard of Austin, Texas if not for Slacker and Dazed and Confused. In fact, there was a nice little coffee table book of Slacker that had been put out. It was terrific, because that was such a local movie and everybody in that movie was some kind of local character, so it had little bios on all the little local characters and had little notes about all the locations they shot and most of those places were still there and still active in ’99. So that was how I learned about Austin, through Slacker. And if you’re earning money, doing part time gigs, this and that, it was much nicer and cooler to be doing that in Austin than somewhere in the North, where it’d be kind of depressing. I love Boston, but it’s not friendly.

Stillman: No, not at all. When you had those gigs, could you walk to work? Or did you already have a car?

Bujalski: I did have a car, yeah.

Stillman: So you have to have a little bit of capital to establish yourself in Austin. You’ve got to have a car. So, I’m sort of surprised that Support the Girls didn’t get a bigger theatrical release. On the internet, it says that Hulu’s the distributor for Support the Girls, but there must have been a theatrical distributor.

Bujalski: Yeah, Magnolia put it out.

Stillman: That’s great. They’re one of the few truly indie, truly cool distribution companies still kicking in a good way. So, how was the casting for that done? How did you link up with Regina Hall?

Bujalski: Luck, you know. You start to kick around who could be right for this, and her name came up early and certainly I was excited about that. And you know, these things tend to be self-selecting. The people who are not interested in your weird little indie are not going to return your call anyway.

Stillman: Were there many people from your personal world in that movie, or is it mostly professional actors?

Bujalski: It’s mostly professionals in that one, and certainly Results as well as mostly professionals. But every once in a while there’s, there’s somebody you can plug into something. It’s always a great pleasure to me to be able to bring in somebody who’s unexpected one way or another. And even with Support the Girls, she was not from “my world,” it wasn’t somebody I knew, but I did have this flash of inspiration when I was trying to think about who we might find for that Danielle role. And I discovered the rapper Junglepussy, who was amazing. We just took it to her reps and said, “Hey, has Shayna ever considered acting?” And that couldn’t have worked out better. And there was a thrill for me to be able to go outside the Hollywood box, because it adds a real spark to the movie.

Stillman: Who played the lead waitress, who’s so attractive and enthusiastic?

Bujalski: That’s Haley Lu Richardson. She’s doing great and she’s on White Lotus now.

Stillman: She was fabulous. Have you been with your managers and agents in Los Angeles for a long time?

Bujalski: I’ve been with my agent for a long time. The manager relationship is newer, but we’re figuring it out. I struggle with my relationship to Hollywood in general.

Stillman: But you’ve got a big credit [Bujalski wrote the screenplay for Disney+’s live-action remake of Lady and the Tramp]. That’s the dream for all agents of indie writer-directors, to get them a Disney gig.

Bujalski: It was a very nice gig.

Stillman: But you didn’t change the plot. You should have had Lady end up with someone more suitable, like the loyal Scottie dog.

Bujalski: Here’s something it took me a while to figure out, something that I learned working with Disney. You don’t want to change anything they have already built the theme park for.

Stillman: [Laughs] That’s very good. Congratulations on weathering those rapids. It must have been interesting. So, the new film. I was enchanted with Annie—

Bujalski: LaGanga, yeah.

Stillman: She’s someone from your world a little bit, isn’t she? Because she’s only been in Computer Chess and this?

Bujalski: She’s from California, but she’s been in Austin for a while. She’s done a lot of storytelling work. She has live performance experience, but she’s not an actor, per se. And it’s that same thing with Shayna McHale in Support the Girls, where you look at somebody and you go, “All right, there’s not a track record that is going to make people comfortable.” And I think people feel when somebody is not a slick professional performer. But in the right role, in the right space, that’s the thing that’s most exciting to me. Going back to Harvard and verite, that frisson of life. I’m all for the artifice and everything you describe, but what I’m hoping is that I might squeeze the most out of cinema by the friction between these things, by the fakery and the reality that cinema does better than anything else.

Stillman: She comes through beautifully. It’s a tour de force. I can’t actually remember her from Computer Chess.

Bujalski: It’s a very small part. She’s one of the encounter groups.

Stillman: Oh, yeah. So you sort of enjoy making fun of these goofy Americans, both the upbeat, power for life angle, and also the no frontiers, no limits group in Computer Chess. You must be more exposed to that out West and in Texas than you are in the East. Or is that just American society?

Bujalski: I think that’s American society. I don’t mean to make fun. I have a lot of sympathy for that, it’s a character type I come back to again and again. And yeah, sometimes it’s goofy for sure. But willful positivity, willful optimism, optimism against all rational belief. In some ways, I find it to be a fairly reasonable coping mechanism.

Stillman: Very good point. And Molly Gordon, how did she come into There There?

Bujalski: Luck, as usual. I’d been trying to get another project together, a slightly more conventional project pre-pandemic, and I’d seen her for that. I was just so impressed with her.

Stillman: She’s sensational.

Bujalski: Having made this movie remotely, she’s the last cast member that I’ve still never actually met in person.

Stillman: Oh, my gosh! She’s so good, what resources she has. I have to say, you were kind of an inspiration for me when I was dead in the water and trying to persuade Castle Rock to invest in Damsels in Distress. I said, “Here all these people doing all these movies that are getting attention, we can do an inexpensive movie, too!” And Greta came out of your world, right? Were you in one film together? Or more than one?

Bujalski: Yeah, we acted together in one movie long ago.

Stillman: Which is like, one of her most famous early movies, the one that consecrated her in the New York Times.

Bujalski: I mean, to see that talent in bloom. I was hired as an actor. I thought we were all on this goofy little indie project together, making it up as we went along. But I do a scene with Greta and realize, “Oh, she’s a real actor.” To go against that power and think, “Oh shit, I’m supposed to hold up my end of this.” I did my best, but she carried me.

Stillman: I like what you said in some interview, that you feel that you’re better in your own movies than in other people’s movies, because you’re so worried about everything else. You’re worrying about your performance less. And you really are excellent in your films.

Bujalski: Even with Molly’s character in There There, I struggled. I realized the first time we got on Zoom together just to read through the scene, I thought I was writing for a 25-year-old woman. And when I heard her say it out loud, I realized, “Oh, there’s a lot of 45 year-old man that crept into this script.”

Stillman: You think so?

Bujalski: We cut some of that out.

Stillman: I thought she was perfect.

Bujalski: Well, she’s fantastic. She had to fight through my script to get there. I couldn’t be more pleased with the result. But you know, now working with people in their 20s, getting at that liminal thing when you’re watching people make decisions and feel each other out in real time, those responses do tend to get more automated as we get older. I know I have to do a lot more trusting of the actors, a lot more inviting them in and saying, “You’re 25 now, I don’t know a whole lot about that. Talk to me, help me, let’s make this feel right.”

Stillman: Well, in about 15 years, you’ll know more about it as your children get older.

Bujalski: My kids are now closer to that age than I am. I do look to them, certainly.

Stillman: What is your casting process? Do you ever have an open call and just bring in tons of actors for certain parts?

Bujalski: It’s situation-dependent and role-dependent. Sometimes, you’re going down the Hollywood list, which is my least favorite way to do it. But sometimes it works.

Stillman: Does everyone read? Or do you hire people without reading them?

Bujalski. It depends on the situation, again. And as you know, when you’re dealing with bigger people, sometimes that’s not allowed. I love reading whenever possible. And I also wish that more of the bigger actors were more open to it. I feel like it’s as much a chance for them to feel me out as vice versa.

Stillman: A friend at an Academy luncheon sat next to Jack Lemmon and my friend was struggling casting his film. He was talking about this thing of actors not reading for roles and Jack Lemmon expressed astonishment and said, “Why wouldn’t an actor want to know that the director liked what they were gonna do? Wouldn’t they want that? They want to be stuck on a set with someone who doesn’t like what they’re doing?”

Bujalski: Yeah, sometimes these actors would perhaps be willing to do it. But it’s a status thing that the agents have to enforce. It’s not my favorite part of the job, trying to sift out those politics.

Stillman: It’s a business game. It’s unfortunate. There are some people who are not that big and who lose a lot of opportunities because they have some manager who flatters them by saying, “Oh, you’re offer-only.”

Bujalski: Right.

Stillman: I think there’s a lot of harmful flattery in the business, except when it’s directed my way. Someone said something about how horrible it is that people talk about the “content.”

Bujalski: I’m not a fan of content.

Stillman: Is it a movie or a TV show? “Oh, it’s content.”

Bujalski: I miss cinema and I don’t know how to adapt to “content,” but here we are.

Stillman: Well, I think there’s a way we can really try to foment the cinema experience and try to get back to when people had to go to the cinema to see our films when they come out.

Bujalski: That would be nice.

Stillman: But it’s a big fight. It’s a big fight.

Bujalski: Yeah, and I can’t turn the tide. I came to all this stuff too late, anyway.

Stillman: I was staying near the Laemmle Sunset 5 back whenever Funny Ha Ha came out, in some tragic mood 12 years between films, walking around and looking at your posters and thinking, “This looks really interesting.” What year was that?

Bujalski: It had a strange lifespan. It’s a 20-year-old movie. We finished it in ’02. But it was not playing at the Sunset Laemmle 5 until ’05. So it was a long haul to get there. But so lucky, too.

Stillman: Yeah, it’s great to be in a cinema like that.

Bujalski: It was a great experience. We had a beloved, sweet, angel-hearted investor who essentially just wanted to see the movie on the screen. And, when nobody else would put it out, said, :Well, what would it cost to self-distribute it?” So, in addition to all my other hats, I got to be the writer, director, actor, and distributor, which I had never dreamed of as a child. But we did it for a couple movies, and I certainly learned a lot.

Stillman: And how many play dates did you get for that?

Bujalski: It’s a good question. It was such a different era that we did pretty well. I don’t remember the exact number, but we did get a good number of bookings and a good number of cities, and we kept it on screens, on 35 millimeter, for six weeks in New York, which seems unthinkable now. Marvel movies can get to six weeks, but that’s about it.

Stillman: That’s great. It really shows how important some theatrical is for exposure, because in some ways your career dates from that release. That’s when everyone started talking about you.

Bujalski: And perversely, because it took three years to get that movie out, I had enough time to make another movie in the meantime, which gave an illusion of being—

Stillman: Prolific.

Bujalski: Prolificness, yeah. Which I’ve not been able to maintain since.

Stillman: And you edit them all?

Bujalski: I’ve edited most of them myself. On Results and Support the Girls, I worked with editors who were great.

Stillman: Isn’t it lonely editing on your own?

Bujalski: Yes. But with this movie, There There, it was such a bizarre thing that we were doing. I knew it was going to take a long time, and we probably couldn’t afford to keep anybody around for a long time anyway. At least with Results or Support the Girls, it’s in a conventional enough idiom that you can have a common language with somebody and you can delegate. With There There, it was so weird. I didn’t know what it was. I thought the only way to figure this out is for me to sit down and bang my head against 80 hours of footage until I find it. So it had to be a lonely process, because I didn’t know how else to talk about it.

Stillman: Yeah, I haven’t wanted to talk about that directly, because I think it’s better if people just take a film as they find it. But I think by being oblique, maybe we’ll intrigue people more. Can you talk about anything else? Or is it all under wraps?

Bujalski: Well, it’s not under wraps, but I’m superstitious.

Stillman: Okay, yeah. At early stages, it’s fair to keep mum. And there is theft.

Bujalski: Oh, no one’s gonna steal any of my ideas. I feel fairly confident about that.

Stillman: Never feel confident.

Bujalski: Okay. Thank you so much, Whit.

Stillman: Good luck, and safe return to Austin.