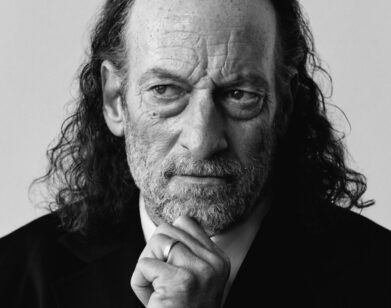

Head to Head: Stephen Jones

PORTRAIT BY ROSE SCHNEIDER

Anna Piaggi of Italian Vogue, as famous for her eccentric headgear as her styling, once described Stephen Jones as “the maker of the most beautiful hats in the world.” Today, his sculptural pieces are celebrating their 30th anniversary, and have (literally) turned hats on their heads, taking them out of the shadows of tradition and into the spotlight, with clients like Christian Dior, Galliano, Jean Paul Gaultier, Marc Jacobs. Good luck keeping up with this Jones, who launched his book, Stephen Jones & the Accent of Fashion (ACC Editions), in Paris last week, and whose work is currently on view in an exhibition of the same name at Antwerp’s Fashion museum, MoMu.

We had an orange juice with him at Paris’ Plaza Athénée after Fashion Week, and talked about the secrets of millinery, Great Britain, and headgear on a budget.

ALICE PFEIFFER: You have just released the French edition of your book in Paris. What was the lesson of putting that together?

STEPHEN JONES: It’s a great book. It’s crazy re-examining the past. People pay lots of money for regressive therapy, and that’s the easier way to do it. The portrait on the cover was taken by Nick Knight. The backdrop was my assistant holding a piece of paper. Eventually the camera jammed, and he just said ‘I hope we got it’ and that was the picture. And it’s one of Nick’s favorite pictures.

PFEIFFER: How did you get into millinery?

JONES: I was at Saint Martin’s college learning about women’s fashion and I just didn’t have a clue about garment, so my tailoring teacher took pity on me. He owned a couture house, and I went as an intern into the tailoring workrooms. The tailors were all competitive with each other but the millinery workroom was all girls who worked hard and played hard. I just thought, “I think I want to be with them.” Not because I had this big thing about hats, not at all, I just wanted to work in a fun place. I was a punk, and they were accepting.

PFEIFFER: Do you remember the first hat you ever designed?

JONES: I had asked to be transferred to another department, and so the head of that department asked me to present a hat. It was Friday and I had until Monday. I went home and got some cardboard and spray mount, and a plastic flower. You know, in England, before they had loyalty programs at the petrol station, you used to get plastic flowers free with petrol, because they were considered fabulous new technology — they never die, all you have to do is dust them once in a while. And to a punk mentality that was fantastic. I sprayed them on and everyone thought it was terribly modern.

PFEIFFER: So what appealed to you about hat making?

JONES: Well, with fashion I could understand the form of the body, which you wrap in fabric and need for protection etc. But there was something about hat making, because it was a constructed object, which I felt more home with.

I’d always made things, cardboard boxes into ships, and suddenly all these things, history, construction came together.

Also, my best subject after art was physics, and they never knew what to do with me—but actually, high-level physics is art. So suddenly millinery brought all these things together: strain, weight, force.

PFEIFFER: And how did you go about turning this passion into a business?

JONES: I came to Paris to be a design assistant for hats, but I didn’t think anyone would be particularly interested, that just what I loved. I then came back to England with no money and fairly unsympathetic parents, so I started making hats for friends. It was at the time of the Blitz Club and New Romantics, and I was driving a truck during the day—I made a fortune! I was making hats in the evening and paid my debts and bought fabric and a sewing machine, and had a little hat party.

PFEIFFER: And then?

JONES: It’s not that I wanted to change the world with hats. But it’s just that at that time, fashion wasn’t about that, it was about self-expression. Steve Strange who run the Blitz Club also worked in a trendy shop in Covent Garden. They told me they didn’t use the basement and offered it to me. To my complete surprise, less than a year after leaving college I opened my own shop. That was 30 years ago last week.

PFEIFFER: What’s the difference between a hat designer and a dress designer? Is there a hierarchy?

JONES: To be a dress designer you have to have an ego, know how you want the world to be, otherwise you’ll never get anything done: It will be your clarity of vision that is going to lead people. But as a milliner, it’s very different, you have to negotiate things, it’s always about working with people. Whenever I take hats out in front of John [Galliano], I never know if he is going to like them. You never do. And today, I do pinch myself every time I go into Dior.

PFEIFFER: Your budget has changed slightly since your truck-driving days. How does it affect your designs?

JONES: The nicest thing is to take a fabric that is 200 Euros a meter and use it like it’s a piece of old cotton, and then to take that piece of very simple white cotton and cherish it.

PFEIFFER: And today, they seem to be making a comeback?

JONES: When I started, nobody was showing hats except Karl Lagerfeld. They were the kiss of death, and they made everything look old. But then they lost their association with etiquette, and it became about self-expression. Today, if Jennifer Lopez is running around with a floppy hat, all of a sudden girls want to wear it too. Or that little trilby-ish type hat that Beyonce and Christina Aguilera have been wearing: if a girl is going on a night out she might go out to H&M and buy one just like that.

PFEIFFER: Do you have any advise for hat-lovers on a budget?

JONES: Go and buy a beret. It’s the best hat in the world—male, female, Faye Dunaway in Chinatown, Marlene Dietrich—it can be worn in so many different ways. John [Galliano] wore one last week. You can buy a very nice French beret and spend 500 Euros, but you can also buy a very nice one made in Czechoslovakia for $2 on Canal Street. A beret is like the T-shirt of hats.