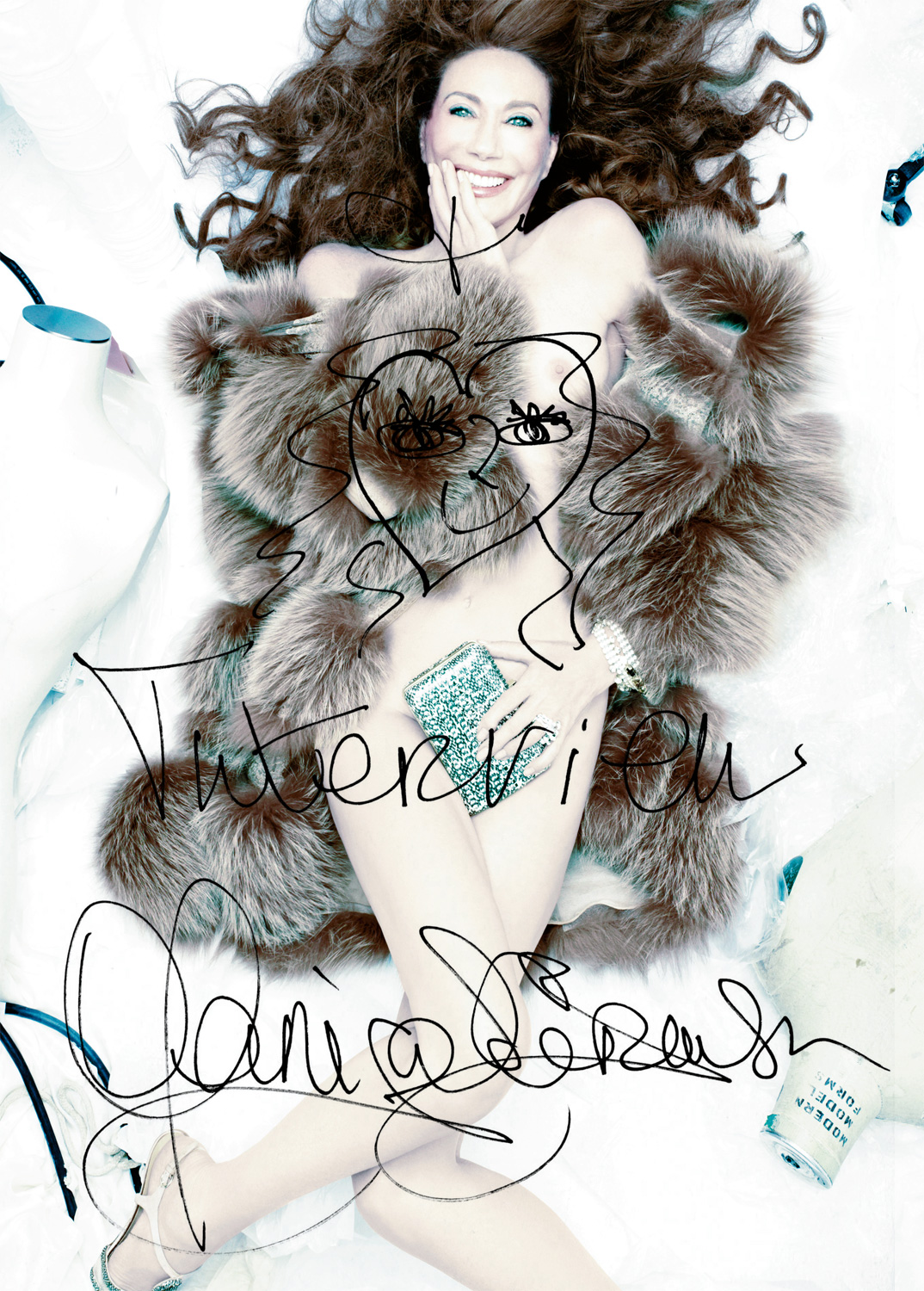

Marisa Berenson

Marisa Berenson has spent a good portion of her time on this planet being photographed, whether as a model playing muse to the likes of Richard Avedon, David Bailey, Steven Meisel, Helmut Newton, and Irving Penn, or as an actress appearing in films such as Luchino Visconti’s Death in Venice (1971), Bob Fosse’s Cabaret (1972), and Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon (1975), or as a woman whose very life has unfolded like a transatlantic cinematic narrative filled with lots of high glamour, dramatic twists, and tragic turns. So there was no shortage of material to mine in compiling the new book, Marisa Berenson: A Life in Pictures (Rizzoli), a sweeping visual biography due out next month. The book traces Berenson’s journey: from growing up as the daughter of U.S. diplomat Robert L. Berenson and countess Gogo Schiaparelli in the substantial—and at times difficult—orbit of her grandmother, the legendary designer Elsa Schiaparelli; to her move to New York to pursue a career in modeling under the tutelage of Diana Vreeland and the iconic image of her that graced the covers of magazines like Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, Time, and even Interview; to her forays into film; to her emergence as the definitive “girl of the ’70s,” as Yves Saint Laurent once referred to her, as she became a pop personality who transcended fashion, film, and even the pixie dust of her famous lineage. But as much as Berenson’s very public life shaped the world’s image of her, what was happening behind the scenes in her private life shaped the woman she has become, including the death of her father, which drove her to seek out a new kind of independence, the birth of her daughter, Starlite Randall—the product of her brief marriage in the mid-’70s to first husband James Randall—and the loss of her younger sister, the photographer Berry Berenson, who was aboard one of the planes that crashed into the Twin Towers on September 11, 2001.

Today, at 64, Berenson is easily recognizable as the girl in those earlier images with tawny skin and bright doe eyes. She’s still acting, and appeared in Luca Guadagnino’s Academy Award–nominated, multi-generational epic I Am Love. She also continues to be an influential force in fashion, having helped her interviewer here, Tom Ford, mark his highly anticipated return to designing womenswear last fal by modeling his Spring 2011 collection as part of an intimate presentation in New York City. Ford recently spoke with Berenson, who was on the set of the television series Le sang de la vigne near Angoulême, France, from his studio in London.

TOM FORD: How did your family react when you became first a model and then an actress? I mean, your father and his family can certainly be described as intellectuals. Were they supportive of what you were doing?

MARISA BERENSON: Well, my father died just at that moment, which gave me all the more incentive to go out and live on my own. I adored my father—I was more attached to him than anyone. And he was encouraging to me, but unfortunately he died the year that I moved to New York and started modeling. I was just 16 going on 17, and everything started to take off at that moment. Diana Vreeland, who was the editor of Vogue at the time, had sent me to Paris to do the collections with David Bailey.

FORD: David is hysterical. He photographed me two days ago, and he always makes me laugh.

BERENSON: Isn’t he wonderful? He did my first big Vogue story around the collections, which was a big deal. But my father died, so I stayed in New York and lived on my own. My grandmother [designer Elsa Schiaparelli] was not happy at all. She hated the fact that I was a model and I never really understood why, but then Diana used to say to me that, maybe, she wanted me to get married and settle down and not have a hard time the way she had. Or my grandmother just didn’t like the fact that I was in the fashion world. I don’t know—it was a mystery to me. But she wasn’t at all happy, and never made much com- ment except to ask me how I could go out dressed the way I was, looking like a crazy person . . .

FORD: I read that your grandmother thought that your clothes in the ’60s were frightening and that your generation had lost all sense of style and beauty and chic. Do you ever feel that now when you look at younger generations, or do you feel like it’s all okay?

BERENSON: Hmm . . . I think there’s so much choice nowadays and incredibly talented people like you who keep the style and elegance going in this world, because there’s not enough of it. Also, in our day, maybe it wasn’t so chic—

FORD: Oh, god. For me, looking at it, it seems so chic.

BERENSON: Some of it was. I guess my grandmother didn’t like all those miniskirts. She didn’t think that was very pretty. But I do think that there were some really beautiful things in those days, and I think there are today, too, except that now there is less individuality, less personality. It almost seems like everybody wants to look the same. In our day, I think there was more freedom. What was going on in the culture all seemed very new and creative—peace, love, and rock ’n’ roll. Then there was also that side of elegant designers like [Yves] Saint Laurent and Valentino, who were just the most extraordinary designers, whose clothes I love to wear. So there was a mixture of things back then. Now there’s a mixture, too, but it’s sort of like everybody is trying to capture the essence of the past a bit, and there’s not enough elegance. We celebrate vulgarity more nowadays than elegance and style. I think that most people don’t have their own style. You know? They’re just trying to copy everybody else.

FORD: This might be a difficult question for you to answer, but do you think there’s a burden in being a great beauty? Is it a blessing? Is it a curse? Do you ever feel that you were not taken seriously as an actress or in life because of your beauty?

I used to go into [Irving] Penn’s studio, and there were always very sophisticated women around–you know, Mirella [Pettini] and Birgitta [Aflercker]. They all had very high cheekbones and skinny noses and looked like ladies.Marisa BerensoN

BERENSON: Well, first, I never said I was a beauty. I never felt like a beauty.

FORD: Well, you are! You are!

BERENSON: [laughs] Thank you, Tom. But I do think I learned to accept myself through the eyes of others when I was young because I wasn’t brought up to think that I was beautiful or told I was beautiful. So when I started out in this career, I was astonished actually. I used to go into [Irving] Penn’s studio, and there were always very sophisticated women around—you know, Mirella [Pettini] and Birgitta [af Klercker]. They all had very high cheekbones and skinny noses and looked like ladies. They were very sophisticated, but I looked like a child. I had a round face and a nose that wasn’t aquiline at all, and I didn’t understand what people thought. So since I never felt that way about myself, I just never got in the way, you know?

FORD: Do you think your looks were a way to mask that you were shy or self-conscious, or did you actually begin to gain confidence? Would you call yourself confident today?

BERENSON: I think I was very shy and introverted when I was younger, and yet, when I got in front of the camera or went out on the town, I was able to go out half-naked and do anything. [laughs] I could pose in the nude and do all kinds of things that were completely contrary to being shy. Actually, I think I expressed myself better when I was young through the lens and through acting—through all of that, I was able to really set myself free and let go and be who I wanted to be and who I dreamed of being and even be other people. I did feel that I could slip into the skin of many personalities and many people. In real life, I think I was much shyer, probably, and more insecure. And as I get older, I feel better about myself because I’ve done a lot of spiritual work on myself and balanced myself out, and so I feel more confident about myself as a person and as a woman. It’s not easy to advance in life if you don’t just at some point embrace who you are and say, “To hell with it.” [laughs] I’m getting older now and want to do it as gracefully as possible, but I feel better as a person, inside of me. I’m able to express myself in ways that I couldn’t when I was younger.

FORD: You mentioned spirituality, and I wanted to ask you about that. I was raised Presbyterian, but I am actually quite spiritual in an Eastern way, and I often struggle with the materialistic world that I am a part of and this desire and insecurity and materialism that I create. Did you struggle with that? I mean, here you are, a very spiritual person, yet engaged in something that many would call superficial.

BERENSON: I was thinking about this, actually, in a book I wrote called Beyond the Mirror, because I feel exactly that way. When I was a child, I became aware of having this very existential feeling about life and who I was and what I was doing here and what my purpose was and my mission and who is God and all of that. And I started to search and was actually even tempted to become a nun and go to a monastery.

FORD: Do you still have that desire now?

BERENSON: I do. [laughs] I used to go on a lot of retreats, but maybe when I get older I’ll finish in a monastery.

FORD: I like the idea of you in a nun costume. If you do decide to be a nun, I’d like to be the first to photograph you in a habit. [Berenson laughs] Maybe I’ll build my entire collection around a nun’s costume. But I do know that your grandfather [Count Wilhelm de Wendt de Kerlor] was a theologist. Do you think he had anything to do with this quest for spirituality?

BERENSON: He might have genetically, but when I was young I had the same turmoil that you have—how could I be in this world that people consider superficial and love it so much and love all these beautiful things, and at the same time, want to be the most spiritual person and become a nun? It didn’t go together. So I was battling with all of that until one day, having followed many teachers and masters, I realized that you could do both. You don’t have to be a nun or you don’t have to be poor to be a good person or a spiritual person. On the contrary, I think that sometimes it’s even more difficult to stay on the right track and the path of light when you’ve got all of these things going on around you that are temptations . . . I think it’s more of a challenge sometimes, and we are tested more as spiritual beings when we are on this kind of path. I found myself being tested a lot in life like that to see if I really keep the faith, if I stay on my path, and I’ve never wavered. I’ve certainly tripped and fallen over in my life, but I’ve never wavered from the profound feeling of having faith, which is sort of what has gotten me through everything in life.

FORD: I finally came to terms with it by really thinking that at this moment in existence, we’re actually material beings on this Earth, and we touch and feel and there’s physical sensation. So I just visualize it as if I’m just swimming through all of these things around me, things that I experience and that I’m able to see and enjoy the beauty of, while also maintaining the fact that these things are not ultimately truly important. I view it as if I’m swimming from point A to point B, and that I have the great fortune to move through all of these things without maintaining a greater attachment to them.

BERENSON: Exactly, that’s the way it is with me. You don’t want to be too attached to things because they come and go and you lose them, and what’s important is to keep one’s self, one’s inner core . . . to keep that.

FORD: When one has spent so much of their life in front of the camera, as you have, how do you feel when you look at photos of yourself from another time? How does it feel when you re-visit these images from another time?

BERENSON: I’d say it’s been a journey, because I am not somebody who lives in the past. Other people live in my past much more than I live in my past.

FORD: Do you live in the future or in the present?

BERENSON: I live in the present—obviously, with the hopes for the future, too, dreams that I try to realize. But looking down this path of the past, I’ve felt an incredible mixture of wonder, gratefulness, and melancholy. A lot of those wonderful people I’ve known are gone now, but I’ve had such incredible luck working with such amazing people that I really loved, too. All of those wonderful masters and teachers and wonderful people, from Diana Vreeland to Irving Penn, [Richard] Avedon, Luchino Visconti, Andy Warhol—all of these amazing people who meant a lot to my life and were very important and who have left a mark. I think we’re all marked by the people who come into our lives and really mean something, so looking down that path and looking at all those people that were and are not anymore, as well as that whole period in time where we were so young and carefree in a way, but also not so carefree, because I was going through all of these things and questions about life . . . It’s such a different life now. I miss all of those people.

It’s not easy to advance in life if you don’t just at some point embrace who you are and say, ‘To hell with it.’Marisa Berenson

FORD: Is there a separation between Marisa, the icon, and Marisa, the woman? When you look at some of these pictures, do you feel as though you’re almost looking at someone else?

BERENSON: It is a strange feeling looking at pictures of myself like this because you’re right, there are so many facets in oneself, and as I said before, I love to be a chameleon. I love playing parts and becoming someone else in pictures. In some of them, I hardly recognize myself. I think, “Goodness, is this really me? Do I really look like that? Did I really do all this?” So it is strange to look at those pictures, because you just don’t realize how one is able to transform oneself.

FORD: Did you appreciate it while it was happen- ing to you?

BERENSON: I loved it. I had so much fun. Oh my god, it was so great. I still love it, you know? I still have fun. I’ve never been blasé about anything. I love having experiences and working with great people and the creativity and adventure of it all. I think it’s when I’m happiest.

FORD: You are immortal. [Berenson laughs] Look- ing through your book, there are images that peo- ple will be looking at hundreds of years from now in the way that we now look at women and celebrated beauties in paintings from other periods. What will those people not know about Marisa Berenson, the person, the woman?

BERENSON: Oh, I think quite a lot. [both laugh] I’m a very secretive person. I have a secret garden, as they say. I’m not shy, but more private—private about publique, you know? I don’t like people who reveal everything about themselves. Nowadays, I find it incredi- ble how people just go on television and do all these reality shows about their private lives and their inner I-don’t-know-whats. It’s horrendous to me. I’m the opposite of that. So, yes, there are a lot of things that are inside of me that I don’t reveal, which I think maybe creates, to people who don’t know me, an impression of something . . .

FORD: Of course, because people only have the images in their minds, so they can’t possibly know who you are. They’ve projected their own ideas of who you are onto them. It’s often strange when people meet you because they don’t really know you, but they feel as if they do.

BERENSON: But they don’t, really. That’s why, too, I think one can reveal a lot of emotions and sensitivities and things in other ways. I mean, I would love to one day do a part in a film . . . I think that there are other things that I’d like to be doing in film— other kinds of parts that nobody has really exploited in me. I think most people don’t have much imagina- tion, you know? They sort of see me in a certain way, and it doesn’t go beyond that because of Barry Lyndon [1975] and all kinds of sophisticated movies that I’ve done, which are beautiful, but have crystallized me in an image—which, on the one side, is nice because I love Barry Lyndon. If I die tomorrow, I will have done at least that film. But the thing is, as with all actresses, one wants to go far beyond what one has done and surprise people and also oneself.

FORD: As an actress, do you think you could let go completely of your physical beauty if the role demanded it? Or, because you have been in front of a still camera for fashion shoots for so many years, are you conscious of what you’re looking like visu- ally? Because great models very often see themselves through the lens of the camera and are holding their head right, stretching their neck, moving the right way, and know what their hands are doing. Are you able to let go of that as an actress?

BERENSON: Yes, absolutely, because otherwise you can’t act. If you can’t forget about that stuff, then you’re not an actress. I can’t say it’s always easy to look at oneself nowadays on the screen, because it blows everything up by a hundred percent or so, and not everybody knows how to light actors anymore . . .

FORD: I don’t think anyone does. I don’t think any- one even gives it a thought!

BERENSON: Which is a disaster—and a mistake, too, because in the old days you could be a dramatic actress or a comedic actress or do parts that were dar- ing and forget about yourself, but at least you knew that you were going to be lit in a certain way. Nowa- days, they don’t care, don’t look, and don’t know.

FORD: You’ve had, it seems, quite a few loves in your life. Other than your daughter, of course, who has been the great love of your life so far?

BERENSON: Oh, I don’t know.

FORD: [laughs] Okay, so you don’t want to answer that one. [Berenson laughs] It would get you in trou- ble, but I’m sure—

BERENSON: It would get me in trouble . . .

FORD: So we’ll say your daughter is the great love of your life, all right?

BERENSON: Yes.

FORD: What, then, has been your great- est accomplishment? What is it that you feel the most proud of to this point?

BERENSON: Probably my daughter, too. I mean, when you look at the child that you’ve created—and one like mine, who is so extraordinary . . . I feel that at least I’ve done something right.

FORD: You were sent to boarding school when you were 5 years old. How do you think that affected your own development? Did you long for a closer family life? Or was it okay? Did it influence how you chose to raise your own daughter?

I think we’re all marked by the people who come into our lives and really mean something.Marisa Berenson

BERENSON: I didn’t like being in boarding school because I was very lonely and I felt very abandoned. So it was hard. But on the other hand, it was not easy being at home either. I think when you’re young you feel abandoned, but then it was the kind of educa- tion that one gave children in those days—especially because my parents traveled so much, and they gave us a really good education at really good schools. I was able to learn many languages, which has made me feel like a citizen of the world, and that I can adapt to any culture, any situation. I also have something that I think is a great strength, which is the ability to be alone. I actually like being alone because I don’t have anxiety about it. I was brought up feeling very much alone. So, actually, I don’t mind it. I didn’t send my daughter to boarding school, because even though it was the kind of education that my parents gave us, this generation is different. But I tried to do differ- ent things with my daughter and have that very close relationship with her that’s very trusting and where I can talk to her about everything. I think I wanted that for her because I didn’t have that.

FORD: So do you still have the Chanel suit that you made in boarding school that you used to wear?

BERENSON: [laughs] I don’t! I wish I did.

FORD: How old were you when you wore that suit?

BERENSON: I was in school in England, at Heath- field, which was a very English boarding school. I was there from the age of about 12 or 13 to 15. I used to sneak out on the weekends with this friend of mine. We used to get the high stiletto heels with pointy toes, which ruined my feet. My mother was furious. But I used to only be able to wear them when I went out on the weekends with her. I loved my suit. I was so proud of it. It was black-and-white tweed, and inside it had an orange silk.

FORD: So you can sew.

BERENSON: I can sew, yes.

FORD: I think you should have revolted and made one of your grandmother’s wonderful designs instead of the Chanel suit.

BERENSON: You’re right. But in those days I don’t think my grandmother was making clothes anymore.

FORD: But, god, she made some incredible things.

BERENSON: Oh, yes. The best. She was more of an artist and a creator than Chanel, actually. She was just an incredible surrealistic artist.

FORD: You’ve always been really comfortable with your body, or so it seems, because there have been many, many nude pictures of you. I have had the good fortune of seeing a great deal of your body very recently, and I have to say, you look the same. How do you do that?

BERENSON Oh, god! [laughs]

FORD: You could still pose for nude photographs today. In fact, I think it would make a great picture.

BERENSON: Do you know what I just did, actually? I just did a picture with Ruven Afanador, who cop- ied the picture I did with Irving Penn. I was doing a shoot with Ruven, and all of a sudden the necklace that I wore in the Penn shoot, where I’m totally naked and spread across two pages, appeared at the shoot along with a letter from the man who created it in 1970, who said that that picture changed his life because it made him famous. So he sent along this necklace, and I looked at it, and we said, “We have to photograph it!” So I said, “How are you going to do that?” [laughs] And he said, “I want to photograph it in the same way as Penn did.” So he just photo- graphed me in that necklace and nothing else on.

FORD: I always have a five-year plan, a ten-year plan. I can tell you exactly what I’m going to be doing when I turn 90: I’m going to be living in New Mex- ico, not working in fashion, not making any movies, living on my ranch, probably showing irregularly, and sculpting things out of mud. Now, I know that you have many decades before you reach your 90th birth- day, but what do you want to be doing at 90? What do you see yourself doing then?

BERENSON: Well, my dream is not far from yours, because I dream of having a house by the sea, because I love the sea, where I can grow my own vegetables and have my garden, as well as a spa, where I can swim and massage and meditate and do all kinds of things that I love surrounded by flowers and trees. I’d have olive trees and make my own olive oil, and then little houses on the property where my friends and my daughter and her friends and everybody I love can come and go. So I will be there blissfully.

FORD: Will you let yourself go gray?

BERENSON: [pauses] Well, if I did go gray . . .

FORD: By the way, one day, when you’re 90, you will be breathtaking in gray. I’m not sure I would let myself go gray. In fact, I would be gray if I let myself go now.

BERENSON: I don’t know . . . I think I’m going to try to stay pretty as long as possible. [both laugh]

FORD: Well, gray can be beautiful.

BERENSON: It can, absolutely. But I don’t think I want to be gray. Not for the moment. Maybe when I really get that lovely house I won’t care.

Tom Ford is the President and CEO of Tom Ford International. He is also the director, co-writer, and co-producer of the Oscar-nominated film A Single Man.