Jean Paul Gaultier, Master of Spectacle

Jean Paul Gaultier began his career branded as an enfant terrible. The designer turned Parisian couture on its head by incorporating unexpected materials, pop culture iconography, and a fearless attitude toward societal taboos into a type of fashion that has traded on spectacle and good-natured insouciance. As a child, Gaultier outfitted his teddy bear in the first iteration of his conical bra. He made his entrée into the fashion world by sending his sketches to Pierre Cardin. Over the course of his career, he went on to popularize skirts for men and unapologetically embrace a distinctive and unconventional beauty independent of size, color, shape, or gender. At 62, Gaultier may have outgrown the categorization of enfant, but he has kept an eye towards the innovative and the fantastical.

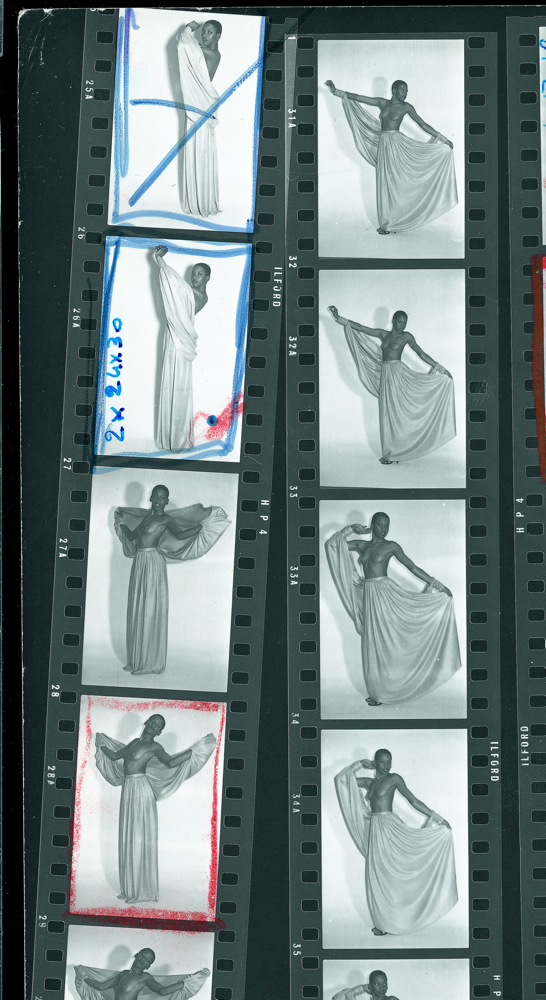

Originally conceived by the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts and curated by Thierry-Maxime Loriot, “The Fashion World of Jean Paul Gaultier: From the Sidewalk to the Catwalk” opens this Friday at the Brooklyn Museum, presenting an in-depth look at nearly four decades of Gaultier’s expansive oeuvre. Organized by a selection of Gaultier’s aesthetic fixations (corsetry, religious iconography, S&M, trompe l’oeil, multiethnic influences) rather than by chronological order, the exhibition showcases 130 haute couture and prêt-à-porter ensembles accompanied by a trove of sketches and ephemera, video, collaborations with Pedro Almodóvar, Madonna, and Beyoncé, and photography from the likes of Richard Avedon, Mert and Marcus, Inez and Vinoodh, Peter Lindbergh, and Cindy Sherman. Animated mannequins, featuring the winking, smiling, and speaking faces of Gaultier (in his signature mariner-striped top) and his many muses (from Farida Khalfa to Kylie Minogue), charge the clothing with the essence and personality of the wearer. “Everybody’s welcome in his world,” Loriot says of Gaultier’s inclusive vision. “There is this generosity of having all types of people who really reflect society.”

Interview recently stopped by the Brooklyn museum to witness the exhibition’s installation-in-progress. Gaultier, hairstylist Odile Gilbert, and her team were on hand finessing the wigs that would top off the installed ensembles. We sat down with the exceptionally warm, quick-to-laugh Gaultier in the museum’s fifth floor painting gallery.

COLLEEN KELSEY: This exhibition has been emphasized as not a retrospective. I know you were a little bit hesitant to do a big museum show. How did you decide that you wanted to do this?

JEAN PAUL GAULTIER: To be honest, yes. For me, because of what I saw before, when I was seeing an exhibition about fashion, it was all historical fashion. Almost 100 percent of the ones I was seeing were people who were dead! So I was thinking, maybe it’s like a funeral, you know, if I am doing one a little too early. But times go quickly. One time [at the Fondation Cartier] it was a bread exhibition. I did dresses with bread. It was funny because it was an experience and another adventure for me. So when I met the Montreal team, I said, “Oh they are different.” It may not be the same thing like a normal retrospective, like, “Number one! Collection ’76! Da-da-da-da October.” I felt they were very active and open to ideas and open to make an exhibition that I wanted. I wanted to have it be alive. Because for me, an exhibition is not to be something boring. It has to be alive and my dream.

KELSEY: The animated mannequins liven things up quite a bit.

GAULTIER: That is an old idea I have—for the model to speak. I remember for the woman, for the model especially, it was “Shut up and be beautiful.” I always thought, for the model, the majority of them are not only beautiful, most of them are super clever. Even in some of my shows, I make them speak sometimes. I love that it’s magical. I always love when there’s a frontier between what is real, what is not real, and what we think is and is not reality. Always. Even in the clothes. I love trompe l’oeil. Like that, they [the mannequins] could speak or make animations of different lives. I love that.

KELSEY: And what has been your experience going back into the archives and re-experiencing things that you made 20, 30, 40 years ago and seeing them now?

GAULTIER: It was very emotional, because first of all, I remember each one of them. I know almost all the clothes, because it’s like my baby. I work on them a minimum two to three fittings—I know the shape. The goal is not a retrospective. What I wanted was more than the clothes, to show those things that are part of my themes, but different things that I’ve worked with: the body, tattoos, etc. It concentrates on elegance from femininity, masculinity, ethnicity, a mix of culture, and all those things that I love. It’s very pleasant to realize that there are sometimes things that I did years ago that can be still now. For me it was like a show, not only a fashion show but living, walking, moving, and people look at it. I love fashion for when we live—the reaction of the people of the town, in the streets—what we look like, how our hair is, our pullover. How people react, and think about you, and see you in a certain way.

KELSEY: Your designs are known for embracing diversity, different cultures, different types of people, gender bending, all shapes and sizes, all of that. Do you feel like the designer has a certain role in society to turn around how we wear clothes and why we wear clothes?

GAULTIER: I think in some ways. My good ones are not to deliver a message or whatever. But I did it like that, because maybe it’s my way of expressing myself. You know, I didn’t say I would do this job because we can change the world. No, I only wanted to do it because it was… at the same time, to play a game, like a charade. Even putting the cone bra on my teddy bear, you know? I love that game. I realized through my sketches people can maybe listen to me, or accept me in some way. So it’s through my work that there are confrontations through the clothes. I think that everybody, by wearing the clothes, can see something in it. There is of course a t-shirt with a protest saying or whatever. So yes, you can express by the way of what you can evoke, you can even lie with your clothes. You can even put yourself in that beautiful way and show how beautiful you are, or hide you. There are many clothes that, I shouldn’t say that can make things, but can accentuate, can be a friend, and maybe help you feel a little more secure sometimes. Of course when women are wearing a trouser, it is different that wearing a miniskirt—it depends on the mood, and you can do both in the same day. But it’s different sensation and different approach. You can say a lot of things with clothes.

KELSEY: The fashion industry has changed since your beginnings. Things have become much bigger, much more global, much more commercialized. Do you feel like you still have the same amount of creative freedom now as opposed to when you were first starting out?

GAULTIER: I think it’s quite more difficult now because there are so many different markets and big groups. So it’s true that it’s quite difficult. It’s [been] 40 years that I have been doing my own collection. I cannot believe it! I am still part of my company and I still make collections that I do like. And it’s true that now you have a code of change. It can be true if now you are owned by a big group, it can be difficult. If there is any advice to give, by my own experience—when I started, it was not the time of the big group, but for me, there was the “big group” because I didn’t have the money. So I think that if you do yourself, and you believe in it, and you want to do it, I think you can do it. I did it, which means there’s a way. [laughs]

KELSEY: You’ve been inspired by so many strong, but different types of women, including Farida Khelfa, Beth Ditto, Catherine Deneuve, Madonna…what is the uniting spirit of the Gaultier woman? How would you describe her?

GAULTIER: Oh, I think a very different woman. Because they are very different and each one has character. It’s women with character. Okay, I like brunettes very much. It can be because me, I have these blue eyes and my hair is a little bit more blondish, but I love people that are the opposite of me. I have different type of models. For example, Farida Khelfa. She is from Algeria. She is just super, and you can see in the video—she speaks in a very funny way. Like, “Ah, I don’t want to do a William Klein thing, I want to do something else!” She is like that, and I love that because she has an opinion. I think it’s like characters, you know, that represent different things. I like them when they are a different kind of beauty. I want to show that differences are beautiful. Be yourself.

There are women in fashion that want to be like all the other ones, but fashion can show your differences and that is beautiful because we are each unique. If there is a beautiful, fine, classical physique there is always something—one shoulder higher than the other, the eyes are dilated, big ears—sometimes there can be a defect of something beautiful. I think we have to use that as the contrary, it’s very inspiring. I like the one you remark on because of the particularity. It’s true that I never did a collection where there was only one kind of beauty. Always, always, always I like to mix. This is why I use professional or not professional [models] at all different ages, because I think there is beauty at every age. Beauty is there, everywhere, but you have to see it.

“THE FASHION WORLD OF JEAN PAUL GAULTIER: FROM THE SIDEWALK TO THE CATWALK” WILL OPEN THIS FRIDAY, OCTOBER 25TH, AT THE BROOKLYN MUSEUM, AND RUN UNTIL FEBRUARY 23.