DESIGNER

How Todd Oldham Built a Fashion Empire With 50 Bucks and a Bolt of Fabric

Speaking with Todd Oldham, one gets the impression that anything is possible. His talents seem to know no bounds: fashion designer, interior decorator, author, TV personality, and all-around creative. Not to mention, he’s perfectly sweet. Oldham, now 63 years old, built a New York-based ready-to-wear empire throughout the ‘80s and ‘90s based on an aesthetic I refer to as “pop surrealism,” though he chuckles at that description. “You know when you can do something but you don’t understand why you can do it?” he asks me. “That was my thing with patterns.” During our sit-down, we homed in on the critical moment that set off his meteoric rise from the Lone Star state to New York, his uneasy relationship with fame, and how a small, inaugural collection—made with 50 bucks, a big roll of discounted fabric, and sewn with help from his mom—would catapult him into fashion stardom.

———

CHRISTOPHER BLACKMON: Hi, Mr. Oldham. How are you?

TODD OLDHAM: Oh, please. Call me Todd.

BLACKMON: What a beautiful home behind you.

OLDHAM: Thank you. I love being here.

BLACKMON: Are you in New York state?

OLDHAM: No, I’m in Pennsylvania. Right where New York and Pennsylvania and New Jersey all touch. This was my country house for several decades when I was in the city working a lot, and COVID just made me give up on being in the city any longer, so I just moved out here full time.

BLACKMON: It looks beautiful. Thank you so much for doing this.

OLDHAM: My pleasure. What on earth made you even think of this?

BLACKMON: Well, I saw the video that you did with The Metropolitan Museum of Art about Andre Leon Talley, and it made me go down a rabbit hole. Then I came across an article about your beginnings and turning $50 into this fashion empire, and I thought it was a very compelling story. What I read was, and tell me if I’m right or wrong: that you borrowed $50 from your parents in Texas, you bought a bolt of fabric, you cut some beautiful dresses out of them, and then you just happened to be able to sell them to Neiman Marcus. I’m sure that’s a very reductive version of the story.

OLDHAM: That’s a whistle-stop. That really did happen. It’s kind of amazing. It just sounds a little made up, but it was very real. I was 17, and I had just moved out of my family home in the country to the big city of Dallas. I’m very, very tight with my family and they were very kind and supportive, and I started my business with my mom right about that time. My grandmother taught me to sew when I was about nine, and I had constantly been around people making dresses, and end tables, and fixing plumbing, just because that’s what we did. We didn’t call people, we fixed it ourselves, and what we didn’t know how to do we learned together. It was really a wonderful, vibrant way to grow up, because we were always so eager to learn.

I was selling some crazy belts I had been making by putting Velcro on both sides so that it could wrap around, inspired by my friend’s crazy, new-wave mother. I thought it would be really fun to get into fashion. I didn’t know exactly what that meant, but I knew I had to get some fabric. There was a fabric jobber in Texas that had this gigantic roll of white thermal underwear fabric, and it had been seriously marked down to maybe 50 cents a yard, and it was 100% cotton. It was a different story in 1980. My parents were very kind to lend me the money to buy that roll of fabric. At the same time, my grandmother was living in Amarillo, Texas, and one of our favorite five and dimes had gone out of business. She went in and bought the entire dye department of this store for a nickel a box. I had these incredibly beautiful dye packages from the ’50s and ’60s that I think shaped my aesthetics, because the colors were kind of faded and very beautiful. I just started mixing things in the bathtub of this tiny little filthy studio, which I continued to make dirtier and dirtier over these next few months.

My mom came over, and we started sewing clothing, T-shirts, and funny little shapes. One of them, which we called a nurse dress, was a sleeveless turtleneck shift. We would sew them up in white, and then I would dye them in my bathtub. I did not have the good sense to wear rubber gloves, so I walked around with gray skin for the next year. It was a funny, funny adventure. My boyfriend, still my boyfriend 43 years later, was named Tony Longoria, and he was a buyer at Neiman Marcus. In Dallas, all 11 weirdos kind of ended up knowing each other. He had been aware of what I was doing, and I had gone to New York to show it at Henri Bendel’s. I had the clothing on my back, and I ran into Tony and his boss, a man named Joel, on the street. Joel told Tony, “Why don’t you go have a look at this stuff?” Which was peculiar, telling my boyfriend to go have a look at his boyfriend’s clothing, which he had already seen, but we were being very discreet about the whole thing. The Beverly Hills Neiman Marcus store was about to open, it was a few months prior to it, and they liked it. They placed the order. We ran to the bathroom, dyed up a bunch of our stuff, and shipped it to the Beverly Hills store. It sold out very, very quickly, and started this crazy snowball effect that pretty much has been my life for the last 40 years.

BLACKMON: From the time that you were dyeing in your Dallas apartment to selling to Neiman Marcus, was this like a year later or a couple months?

OLDHAM: A few months, yeah. Everything went very, very fast.

BLACKMON: What gave you the sense to even go to a store? A lot of times, especially back in those days from what I’ve heard, they say, “We really didn’t have a business sense. It was all about creativity.”

OLDHAM: Well, as a designer, an aspiration back in that day is very different from today. There were a handful of monumental success moments for a designer, and one of them, of course, was being in Neiman Marcus. For me, it was just a gigantic honor. Not to mention that Dallas is home base to Neiman’s, and really every human being I knew worked at Neiman Marcus. I still remain the only person I know from Dallas that did not work there. It was so ubiquitous. But the funny part is I wasn’t in any of the Dallas stores.

BLACKMON: How many styles did you produce for them?

OLDHAM: I’m a pack rat, and I do have all that stuff still. I still have the drawings.

BLACKMON: Really? Wow.

OLDHAM: Actually, now the Met has most of it. We deacquisitioned our ephemera to the Met about 10 years ago. We were very grateful that they wanted it, but we found out that we were the second largest ephemera collection that they have at the Met, first being Charles James, who when he passed, they just took the entire apartment out. I didn’t have to die for them to get my crap. It ended up being a pretty colossal amount of things, but it reflects the whole time and everything else that was going on.

BLACKMON: What’s the arc from being in Texas to going to New York full time?

OLDHAM: That took a few years. I worked solidly in Texas while selling internationally for probably four or five years before I moved to New York around ’89. My entire life, I’d been traveling constantly. My parents are very interesting and made great fun choices for us, and so we would move all over the world, always doing something unusual. I was really grateful to get brought up in that manner. It’s good for business, because business is not normal and constantly shapeshifting. You learn how to be present and calm, and participate no matter what the circumstance is.

BLACKMON: As a designer, especially during the ’90s, which is what I know you from, I would call your clothes almost like “pop surrealism.” They’re like these beautiful pop culture references. Was that a departure from what you started out doing?

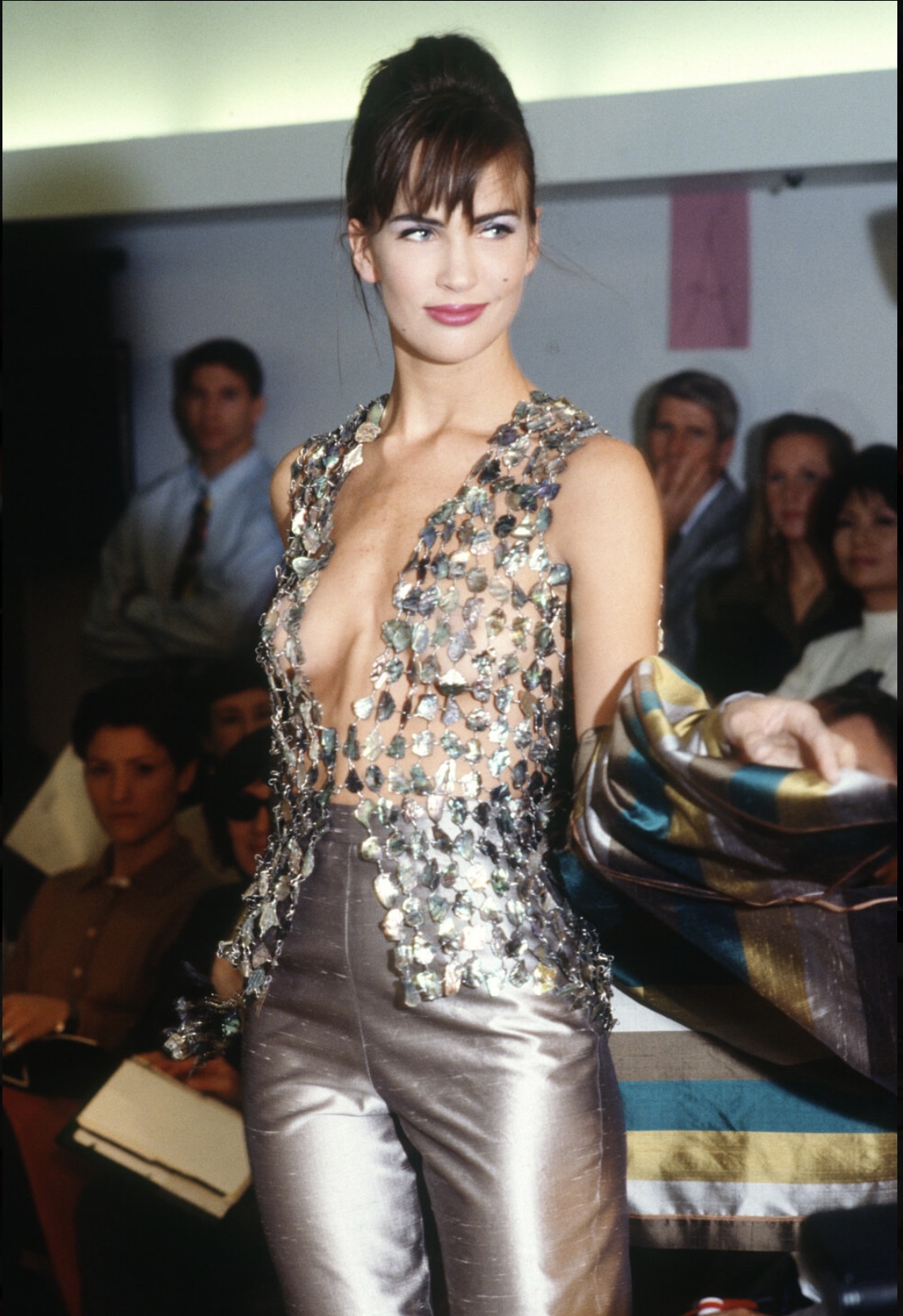

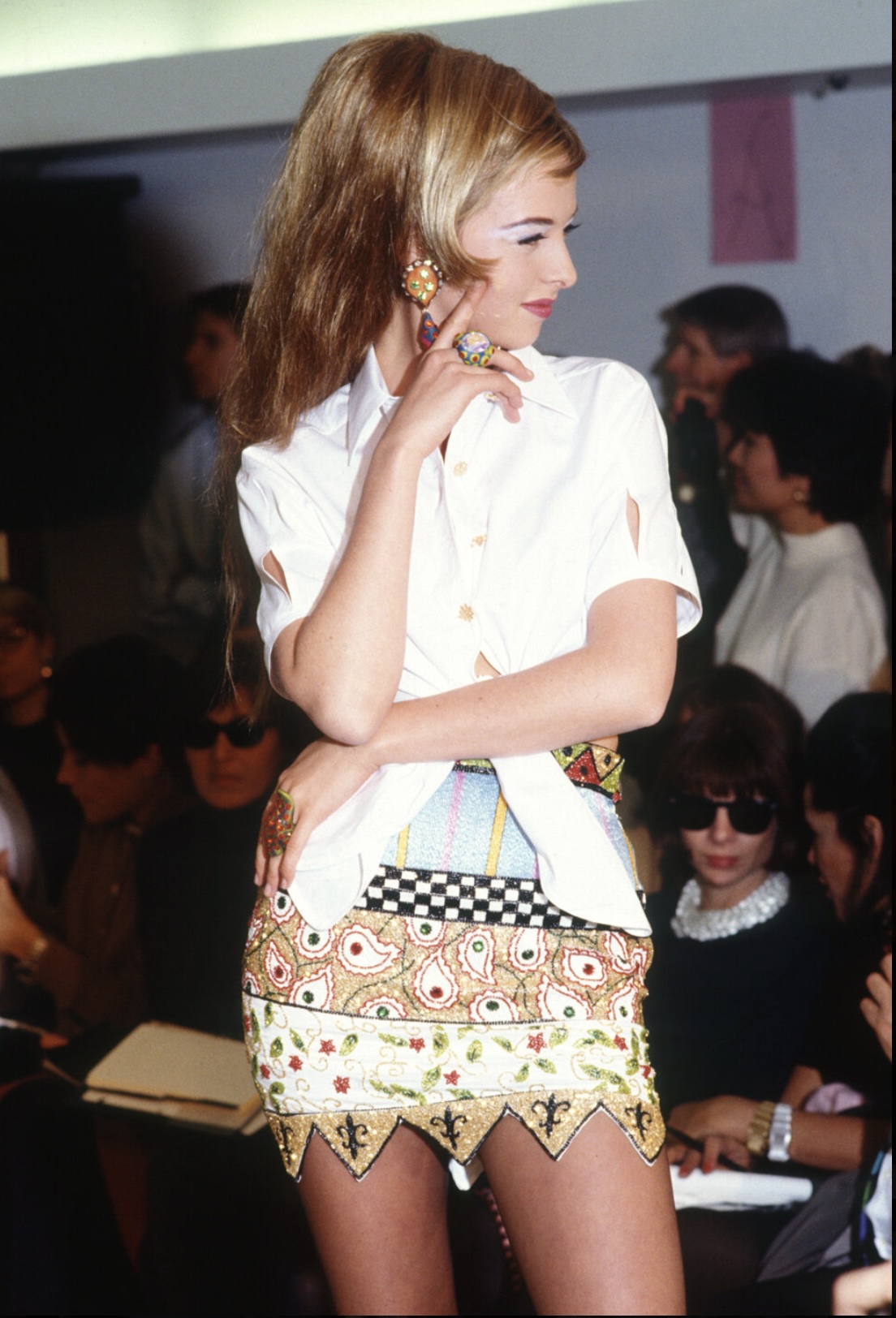

OLDHAM: I made all my own patterns, and I didn’t exactly know how to do that when I started. You know when you can do something but you don’t understand why you can do it? That was my thing with patterns. So those beginning clothes were very oversized for two reasons: I liked that style, it looked interesting to me, but also those were the patterns I could make. As my skills advanced, I was able to execute more of my visions. Then it turned into what most people know me for, this wildly intricate, very complex, completely handmade clothing.

BLACKMON: Did you ever see those early dresses in the wild on women walking down the street?

OLDHAM: I did. I was really lucky through the years to have people like what I do. They didn’t necessarily have to have my version of it, but they enjoyed many other people’s versions of what I did. That was the most interesting thing, to realize people will recreate what I did and put their label on it. I started seeing that. There was this one dress we did called the slash shift, which was just a big T-shirt with these peculiar cuts in it that made interesting volumes. It was really odd, so the fact that stores like The Limited started knocking it off was weird to me, but also made me really happy. It’s like a bellwether that what you’re doing is interesting to a larger group.

BLACKMON: Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, so that’s amazing. How much did those dresses retail for? I’m curious.

OLDHAM: Oh my gosh, they felt very expensive, but they were probably around $100, I would imagine.

BLACKMON: That’s pretty expensive for the ’80s.

OLDHAM: Yeah, they were not cheap clothes, nor were they gorgeously made, I have to confess, but they were interesting. It wasn’t like, “I’ll just wear that other thing I have in my closet,” because nobody had a four-foot wide thermal knit T-shirt dress. I don’t remember anybody back in the day talking about the prices, but in the ’90s when I started doing more of sort of a couture ready-to-wear hybrid, I heard this one sentence over and over, which was, “I love what you do, I could never afford it.” Those words were permanently welded together. That became very boring and sad to me, and which is why I eventually moved on to doing things that people could actually afford. That’s why I got to do this show for about four years on MTV called House of Style. I’d go do a $10,000 dress in the day, and then I’d go show you how to redo your backpack for $1.59.

BLACKMON: I just saw one [episode] recently where you and your design assistant—

OLDHAM: Oh, Angel.

BLACKMON: Yes. She’s an interior designer now, I guess.

OLDHAM: Yeah, she’s really talented.

BLACKMON: You both went to the flea market and reupholstered a chaise lounge?

OLDHAM: Yeah. That was an MTV segment they did on me. I had done a fashion collection called Interiors that was based on interior design, so they interviewed me and said, “Why don’t you show how you did it?” That’s what we did in this segment. I knew how to reupholster because of the way I was brought up. If you need your dimmer switch changed, I would be the friend that would get the call. I’m kind of the only friend that could do all that stuff. It was very normal to me. Then that was so warmly received that they asked me to join. I stayed there for four years. It was fun.

BLACKMON: It was inspiring. In fact, I think I want to do the chair with the fabric dye technique.

OLDHAM: Those are all still tricks I fully believe in today. There were moments where ingenuity counted, and it was just about the thrill of, “What can we do?” The wanting wasn’t, “I want that new thing.” It was more like, “I want to create.” Whether the medium was an old chair that you found, or an old dress to cut up, or a pile of thermal knit fabric intended for underpants, it was all fun.

BLACKMON: Do you think that time has gone, and fashion has become corporatized? The barrier to entry is just so high now.

OLDHAM: Yeah. I think it would be virtually impossible today, but I hope that somebody hears me and goes, “Fuck you, old man. I’m going to do it.” That’s the kind of thing we need. I wasn’t rebelling against anybody. I was just delighted at the tickle of creativity and the thrill. The moth to the flame, I think, is a little bit different now. I have had a pretty complicated relationship with being famous through all these years. It comes very unnaturally to me, and it’s nothing that I wear well.

BLACKMON: You don’t like being noticed.

OLDHAM: I have never, ever been comfortable with that. It’s been from day one, and I’ve had to steel myself, but here I am. I’ve risen to it and I’ve participated, and I’ve been so lucky to be treated so nicely through the years, but it never felt normal to me. Fashion design is very loud. And I was also designing hotels, and making books, and when I stopped doing fashion, I didn’t realize how outrageously loud that system is. I think people who want to get into that medium these days generally have a little bit of a desire for some…

BLACKMON: Stardom?

OLDHAM: Yeah. But it’s just clothes. I love working with all the artisans and protecting all that incredible hand artistry, but I just don’t know about its place in the world today.

BLACKMON: When was the moment where you’re not just Todd anymore, you’re “Todd Oldham,” the brand?

OLDHAM: Well, I’m lucky, because my team was always tight. My boyfriend for 40 something years, my mom and dad, we’re always together. The outside world was changing, but my core never really changed. I didn’t have problems with it, other than sometimes when the outside got crazy. I had a really rough stalker situation pop up in the ’90s, which was kind of a before and after situation. After that, it was very scary. This man was very dangerous and a known murderer. It started involving a lot of other people, MTV. It was not good. There’s a little bit of a permanent dent about that stuff, so if my head’s poking up, it’s because someone’s usually going, “Come on.”

BLACKMON: Are you still in love with fashion, or do you follow it?

OLDHAM: Many of my friends are very chic and fashionable, so I keep up with that stuff. Fashion is a beautiful art form, especially in the hands of people like Victor and Rolf. Oh my gosh, I anxiously await to see what they’ve come up with every time. When you actually see the way couture is constructed, it’s as exquisite and beautiful as fine surgery.

BLACKMON: Are there any American designers that you think are really good at the moment?

OLDHAM: Yeah, I think whatever Marc Jacobs is doing is always very, very interesting. Christopher John Rogers is really clever and very beautiful. There’s so much joie de vivre and integrity in what I see from him. There’s some other new people skirting around the outside edges, and that’s really exciting to me.

BLACKMON: I know that in fashion, we’re supposed to always look forward and never look back. As someone who was born in ’87 and missed the ’90s, the creativity that came out of that decade feels paramount to the present. Do you feel like those days in the ’80s and ’90s were a true Gatsby moment of creativity, or is that romanticizing the past?

OLDHAM: I think you’re onto something, and I’ll share an observation I’ve been making recently, comparing what I felt in the ’80s and ’90s to right now. It has more to do with some sad political shifts. In the ’80s, the beginning of dealing with AIDS was so awful and so scary. You’d go to work on Friday and somebody would be there, and then on Monday, they’d be dead. It was just this endless thing. Then the amount of awful things being said about gay people just felt very much like what’s going on today. What was gorgeous about that time period, and what we can bring with us to today, was the beautiful support in taking care of your own, and making room for others to want to join you too. We hunkered down. Suzanne Bartsch started doing Love Balls. We were there right at the first Love Ball, which was the first event to help people homebound with AIDS. We set up PAWS, which was an organization that helped people keep their animals that were home. That all came from all of us coming together and figuring out how to support our families. I see it happening again today. The government, I think, feels not exactly on our side. It is what it is, but we can be on our own sides, and we can support one another, and bring joy and beauty to our lives. And with that beauty and inspiration that came out of the ’90s, I think we might be prepped for something spectacularly gorgeous if these metaphors are somehow tied together.

BLACKMON: That’s both beautiful and sad. I always think, can great art exist in happiness, or does it always have to come from a seed of sadness or angst? I’m always thinking about that.

OLDHAM: I wonder that too, but we all want to go up the steps. Every experience can take you there. Even the shittiest of ones can be propulsive. Sometimes just knowing what you don’t want to do is just as important as knowing what you want to do. Whenever anybody wrote anything about me, I just tried to stay a little detached, because I knew that it was all opinions. I had to stay secure in that. You can’t let them bury you.

BLACKMON: Wonderful. Thank you so much.

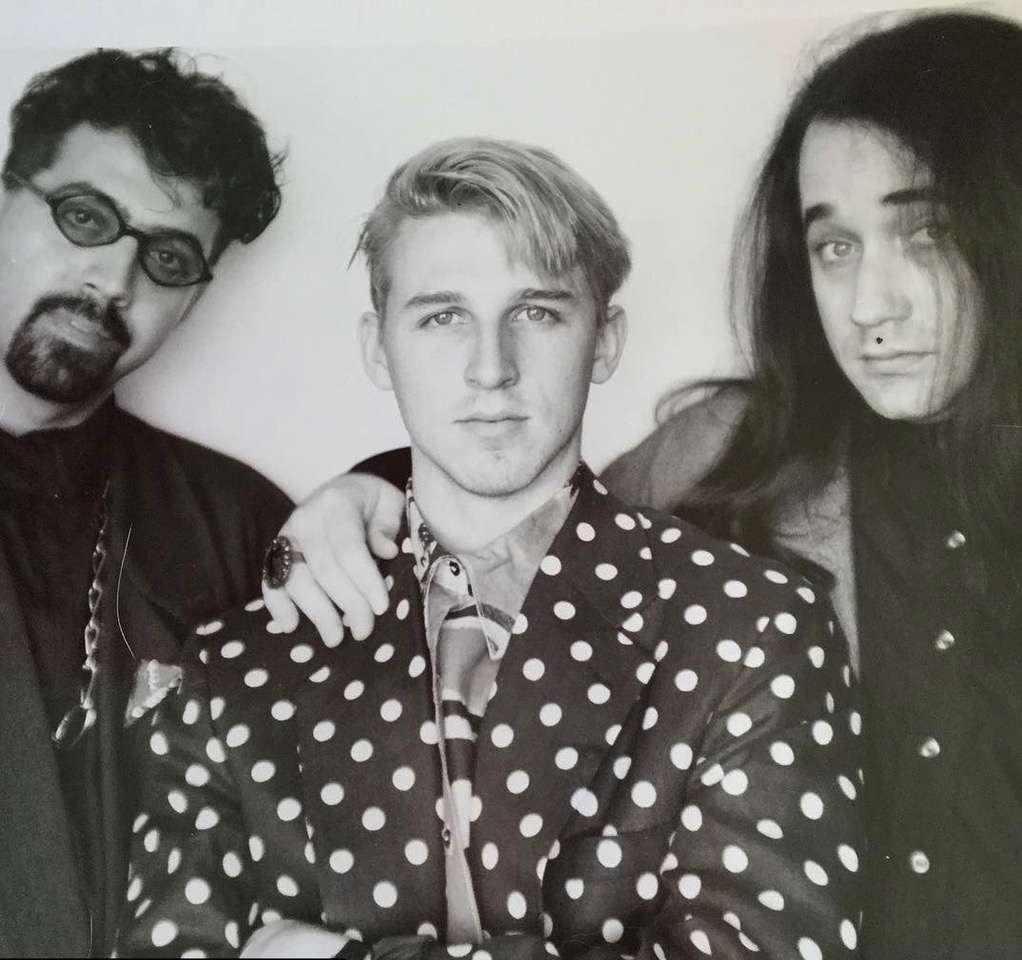

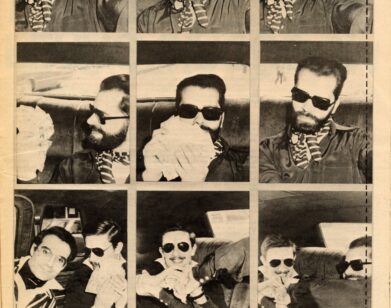

OLDHAM: Thank you for letting me prattle on. I remember being in Interview at right about that time period. My friend Susan T. Garden photographed me for it in front of her studio. That was really exciting. You know how sometimes, you remember the inside of certain moments? I remember how I felt having that picture taken, which was one of the first pieces of press I remember getting. I remember thinking, “Something’s moved now.”

BLACKMON: “My life is changing.”

OLDHAM: Yeah. I had that a couple of times. I remember that in 1989, Onward Kashiyama, the Japanese conglomerate that did Jean-Paul Gaultier and Dolce & Gabbana, brought me on. Suddenly, that was where we got to be, in this showroom with people that were my heroes.