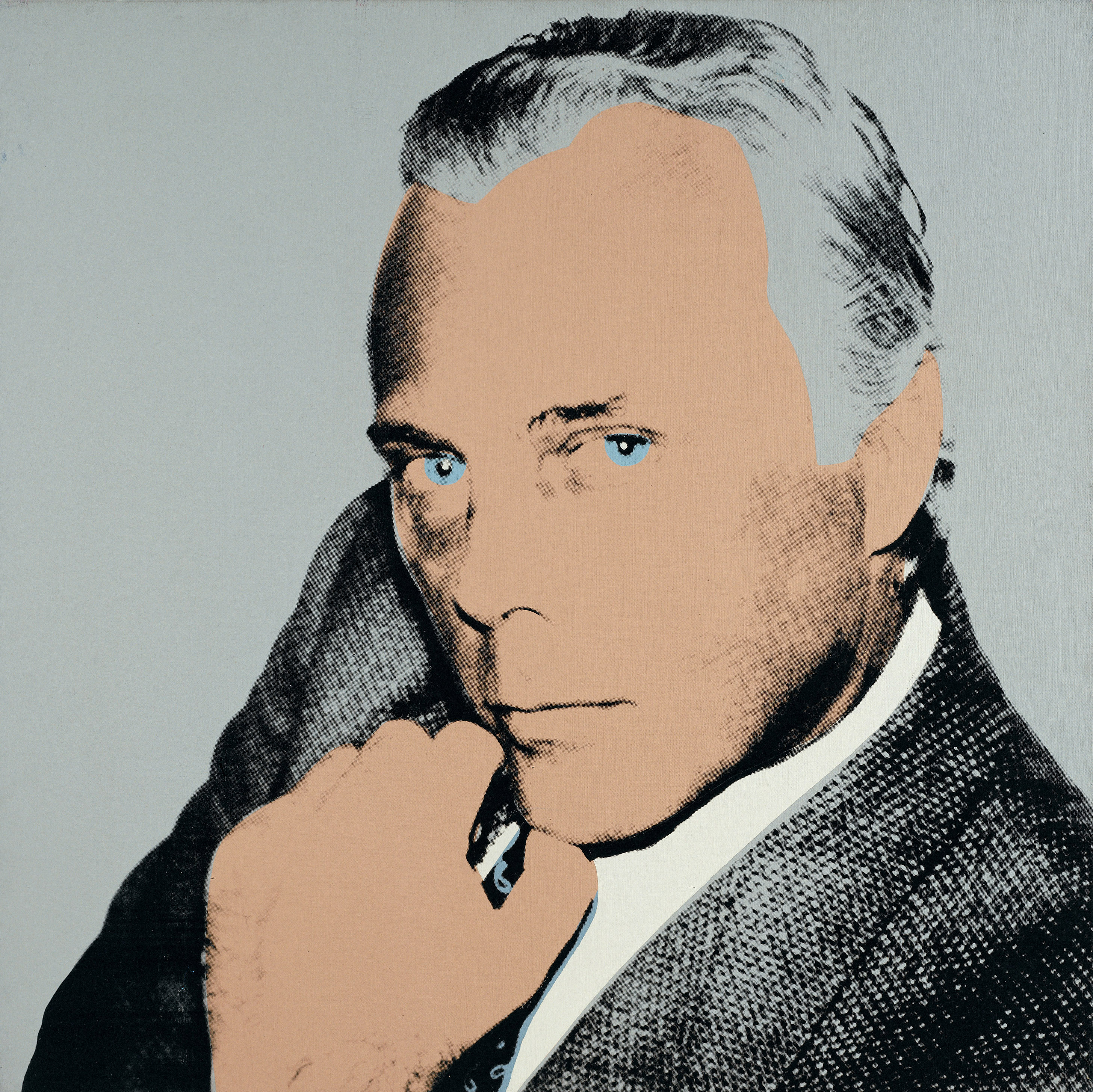

Giorgio ARMANI

When Giorgio Armani first met Andy Warhol in 1980, the fashion designer had just begun a new phase in both his life and his career. Armani had stepped out on his own several years earlier with a succession of menswear and, later, womenswear collections that were iconoclastic from the get-go, blending Old World flair with New World rebellion in a way that instantly connected on both sides of the Pond. Of course, director Paul Schrader’s casting of Richard Gere in American Gigolo-and outfitting of the actor in soft-shouldered, cleanly tailored, free-flowing Armani suits-proved the flash point for the revolution. But the true power of Armani’s work was far more subtle and ingenious. In many ways, he had done for the suit what Andy had done for portraiture a decade earlier: He had taken it apart, dispensed with preconceived notions, and given us something undeniably modern where tradition had once ruled. It’s an approach that has served Armani well over the years, as his company has grown into a multibillion-dollar empire. It’s also one that Andy clearly appreciated. Here, Armani recalls his time with Andy, having his portrait done, and what happened when fashion met art-a love affair that’s still raging today.

INTERVIEW: How did you meet Andy Warhol?

GIORGIO ARMANI: It was a fashion occasion. GFT [the Italian clothing manufacturer] was opening a new showroom. I received an invitation from Andy to represent the fashion scene-and with several others, including [designer] Mariuccia Mandelli, I accepted. Andy stopped me in a corridor for 10 seconds and took a photo to work off of, and when the final portrait was bought by GFT, he made quite a lot of money! Andy Warhol was a genius at marketing himself. Marco Rivetti

[the CEO of GFT] sent one of the portraits to me as a gift sometime later. It is now hanging in my office. Years ago, Andy Warhol and I spent an evening together visiting a variety of New York nightspots. Even though I didn’t speak any English, he wanted me to accompany him so that he could introduce me to the city’s night scene. I have very fond memories of my time with him.

I: What was it like sitting for him?

GA: It was a fascinating experience. Andy was already a very famous artist-possibly the most famous of his generation. I was quite in awe of him. He worked very professionally and diligently. I believe he had an incredibly disciplined work ethic. Behind the showmanship there was a very serious artist.

I: What do you think your portrait captured?

GA: I think that he wanted to portray me as an icon. That is what Warhol portraits do: They elevate the subject into an icon of the pop culture he was documenting. These days, as I am older and wiser, I realize that there is a danger in becoming an icon, as people can see you as remote and untouchable, and they are less willing to tolerate you doing things that don’t fit with their preconceived idea of you. I get really frustrated when people say that a collection is not very “Armani.” Iconic status can be like a pair of handcuffs, especially if, like me, you wish to continually stretch yourself creatively, as Warhol did.

I: Did you see yourself in a new way?

GA: Not really, though I felt that, somehow, in having my portrait painted by the master of pop culture, I had become part of that culture for the first time. And if I am honest, I found this idea rather flattering.

I: Other than your portrait, what’s your favorite Warhol?

GA: Actually, my portrait is not my favorite Warhol. I like lots of his work-his portraits of celebrities like Marilyn Monroe and Elizabeth Taylor, his pictures of domestic items like Campbell’s soup cans and Coca-Cola bottles, but also his more disturbing images like Red Car Crash. I like the way his work acts as a mirror of his time, a celebration of American consumerism and the country’s fascination with glamour and fame and the media.

I: Did Andy say anything to you that stuck with you?

GA: We did talk a bit, but my English was very limited, and I am, in any case, quite a shy person-and so was Andy. So mostly I sat in silence while he painted in silence. Andy concentrated very hard when working, so it was not really a situation conducive to conversation. However, I do remember being struck by how down-to-earth he seemed. I even remember another occasion, one night in New York when we went out. Wherever Andy went, he was recognized by everyone from the taxi driver to important socialites to the doorman, yet he was unaffected and humble and always wanted me by his side. He was not an art snob, and I liked that. He didn’t think that being commercially popular meant that he was somehow less of an artist. This is very much my philosophy as a fashion designer. I have never believed in design for design’s sake. For me, the most important thing is that people actually wear my clothes. I do not design for the catwalk or for magazine shoots-I design for customers. One of my favorite Warhol quotes is: “Making money is art, and working is art, and good business is the best art.”

I: You and Warhol have stayed current and relevant to numerous generations. What do you think is the secret of keeping it new?

GA: For myself, I can say that the secret is to remain true to your aesthetic vision, so that people can see that you really believe passionately in what you are doing. That way, they can relate to your style. At the same time, you experiment-you try new things. For me, this has meant not only adopting new fabric technology and ideas in clothing design but also applying my design vision to cars, furniture, flowers-even cakes!-and exploring collaborations outside the world of fashion, with film and football, for example. Andy’s work shows a similar creative approach. He had a style and he then applied it to different subjects in a way that was both recognizable and innovative at the same time. Anyone who is passionate about what they do will have a better chance of connecting with future generations than those who simply follow transient trends. At least their work will have a distinctive character, and this is what people respond to, I believe.