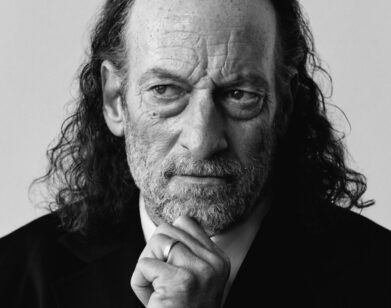

Discovery: Richard Malone

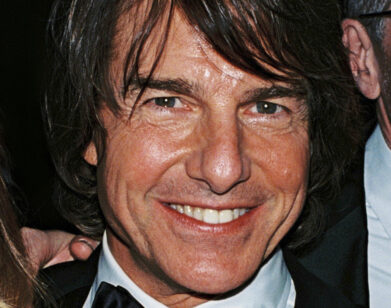

PHOTOS: ROBERT NETHERY. STYLING: MARINA MUÑOZ/LALALAND ARTISTS. HAIR: MAKI TANAKA USING BUMBLE AND BUMBLE. MAKEUP: VICTORIA BOND FOR MAC COSMETICS/CAREN. MODEL: FERN BAIN SMITH/VIVA LONDON. CASTING: DAVID CHEN. PHOTO ASSISTANTS: TOM GREEN AND JODIE HERBAGE.

Considering all the talent that’s emerged out of venerable London incubator Fashion East—Marques’Almeida, Simone Rocha, Craig Green, J.W. Anderson—one of the new ones to know is Richard Malone. Hailing from Wexford, Ireland, the designer nabbed both the Louis Vuitton Grand Prix scholarship and the Deutsche Bank Award in Fashion Design during his BA tenure at Central Saint Martins. And now, from his studio in London and with a few seasons behind him, Malone is sure-footedly building his eponymous line with holistic-minded experiments in form and proportion, inspired in part by the utility-minded workwear of his native Ireland. One of Malone’s recurring motifs is the stripe: for Spring 2017, he utilized graphic lines to shape cheery, candy-colored, future-sporty slit dresses and curvilinear-seamed trousers; tailored, smock-like tops; and sculptural blouses constructed of 3D swirls that cocoon the torso. Interview recently spoke to Malone via phone.

THE TEAM: I’ve got one full-time studio assistant and then we take on interns, but only one or two a season. I like to work with a team that’s honest and gets my process. We can all work in the same way. We don’t work crazy hours or anything. We all take breaks and eat together and do things that I think are quite important, so it’s much more concentrated and focused. I really have to trust people before I have hundreds of people in the studio.

BEGINNINGS: I was aware of clothes in the sense that I would be observant of a lot of different uniforms that were around me, say my school uniform or work uniform, because I started working on buildings when I was very, very young. I became very aware of sorts of clothing and different functionalities of clothes, so I think that’s where my interest of that sort started. I think that society, like working class, Irish, middle of nowhere, the way people used clothes was very interesting. There’s clothes for occasions and clothes that aren’t for occasions. That really interested me, and even though people don’t have a lot of money, there’s communion dresses, dresses in confirmations, dresses in weddings are a big thing, and it’s very interesting to observe. Not a lot of people give it the credit that I think it deserves.

TRANSITION: When I began to first think about Central Saint Martins, the work I was doing was very performative. I had been working a lot more on making forms and sculptures and then, I think, that led into a lot of performance pieces and things that were more like public performance. A tutor on that course actually suggested that I apply to Saint Martins. I had never assumed that fashion was something that was, I suppose, challenging. I had only seen the commercial side of it. When I went to Saint Martins, that’s when I realized that you can do whatever you want. You know, you don’t even have to make a collection, and there are a lot of projects where you don’t actually make any clothes. It ended up just being a course that was really suited to my personality, more of what I actually wanted to do, what I intended to do. I felt that it was a really good way of working. I think that I got in there without actually having any fashion in my portfolio.

UTILITARIAN ROOTS: I think it’s a mixture of observing functionality and actually working in different jobs where clothes have to be functional but also, going from a more performative background and then working in an industry that is quite rigorous, is quite an interesting place to find yourself stuck in. I’m always trying to make clothes that are on one hand quite exciting for me, but then they all develop from me trying them on the body, even myself in the beginning, and then trying them on different women that I know, just to see how they fit and how those forms work. Comfort weighs especially.

STARTING A COLLECTION: I start by focusing quite graphically. It’s a lot of drawing and observing and researching things, so I do a lot of photography or making shapes. I think the way I pattern design is an extension of the way that I draw, in that it’s quite abstract, and that I start sewing shapes together until you start building the forms. It’s very strange in the beginning. Then, with those graphic images like stripes, I have ways of developing and working them from sustainable sources, but also that they don’t look like a hemp sort of hippy collection. That’s just something that you have to consider in designing. I don’t want to do anything that super harmful. A lot of what we do is equally time-consuming, like the stripes, or the right thickness, so when the flash hits the stripe it sort of makes them come alive. It doesn’t really come together until the end when you’ve got those two contrasting things working together: quite organic shapes and these really structured graphic prints or stripes. It’s like a really big sketchbook. It’s a very 3D approach most of the time.

SPRING/SUMMER 2017 COLLECTION: I looked at a lot of men’s, I did a lot of contrast between men’s swimsuits and women’s swimsuits and how women’s swimsuits are completely unpractical. Vintage ones have got these things hanging off them, and to actually swim you’d probably drown under the wake of wool and stuff, so that was the beginning point of the research. Also sportswear, I think, has been applied to my research forever because that’s what we really grew up around, being in these communities where people really buy clothes to function and there isn’t a lot of vanity in it. I’m trying to do it in a way that’s not in that trendy way. Developing shapes, and the fit of the body, and making sure that there are all kinds of things considered, but also having a place within the collection for a lot of different women. I think if you say that your woman is one kind of person, you actually isolate a lot of people who might be interested in something different, who look forward to a new suggestion, a new kind of thing that they can wear that they don’t already have.

WORKING AT BIG BRANDS: They have an excellent design team, but they are so restricted. The houses of Vuitton and Dior, I think, are a bit suffocated by their own archives. They’re not owned by designers. They’re owned by businessmen. They are almost curating the language that you can work in, and I think that’s really, really difficult when you come from a purely creative university. After I graduated, I had a lot of interests with trying to get jobs, and every place was so stale. Instagram has had such an impact on clothes as well. People experience clothes in just a couple of seconds, and then forget about it, and there is this homogenization. It’s flattened people’s knowledge of fashion, and then you have, of course, a corporation telling you stories about these houses. I was [at Vuitton] for a whole year, and they were the most amazing design team, but I just felt that there isn’t a price you can put on the cost of me to work there. You’d have to sacrifice everything that I actually like about fashion to work there, so it just wouldn’t be worth it. I’d actually rather work in a pub because you know you’d have more fun conversation.

STAYING FRESH: I think if I stay really far away from my phone. I have an Instagram because of some of the contacts for our show, we actually have to do posts and stuff, but other than that, I try to avoid it. It takes away from a lot of conversation. I think it takes away from the importance of fashion. It’s like when you go to a museum and then you see an old historical piece of fashion, it looks so amazing because you literally have never seen it before. You’re looking at these things all the time, and I think all these luxury collections doing so many collections with so many looks, that it’s actually really hard to want to buy anything, because it’s too much choice. I think a lot of it is too overexposed. I think that you’re not really opening up a conversation to people who really want to buy fashion—designers being quite detached from conversing with customers or their contemporaries. There’s not a lot of that going on. People are kind of isolated posting things from their phones. I find it really strange because fashion is so attached. It’s a physical object. It’s the same as a piece of sculpture or something, and I think you have to actually see something. You don’t want to go into a designer’s store and see something you haven’t already seen. They all kind of bleed into one and it’s like, “Okay, I don’t know where to look.”

FOR MORE ON RICHARD MALONE, VISIT HIS WEBSITE.